BUTTERFLY CONSERVATION IRELAND ANNUAL REPORT 2024

Contents

• Introduction

• Butterflies of Thailand

• Butterfly Season Report 2024

• Crabtree Nature Reserve Report

• Conservation News

• Garden Survey Report

• Guide to the Butterflies of the Burren

• Species Focus: The wood whites

Introduction

Dear Butterfly Conservation Ireland Member,

Welcome to Butterfly Conservation Ireland’s Annual Report 2024. The year had poor weather for butterflies underlined by the absence of any sustained warm, sunny weather during the summer. The impact on butterfly populations was severe, which you can read about in the Butterfly Season Report. Our reserve performed well thanks to your support and hard work put in by our volunteers and friends. Our small volunteer staff are fortunate to have excellent support from our active membership whenever help is needed. Butterfly Conservation Ireland’s membership remained steady in 2024, reflecting perhaps confidence in our ability to advocate for Ireland’s butterflies and moths.

Your continued practical and financial support is greatly appreciated as we strive to ensure that our butterflies and moths continue to have an important voice in their conservation. We pursue the conservation agenda at every opportunity with submissions to government bodies concerning our habitats. Our recording scheme continues to provide important quantitative and qualitative data; let’s see if we can maintain this in 2025. A huge amount of work was done on the Atlas of Ireland’s Butterflies 2010-2021, and we expect to see this in print in 2025. Our financial accounts were approved thanks are due to our joint treasurers Michael Jacob and Joseph Harding. Thanks are due to Pat Bell for his help in editing this report and to all our members and supporters. We hope that you enjoy reading our Annual Report and we look forward to hearing from you in 2025.

Yours in nature,

Jesmond Harding (Secretary)

Butterfly Conservation Ireland

Butterfly House

Pagestown

Maynooth

County Kildare

BUTTERFLY TRAVELS IN THAILAND by Michael Friel

Thailand has over 400 protected natural areas, including more than 150 National Parks. It has over 1300 species of butterfly, more than India. I have visited just a few of these parks and sanctuaries on six occasions, starting in 2017, travelling for 8 weeks in total and seeing 449 species. On half of these trips, I went independently; the other half were organized tours with a guide. Three of the visits were to the north, two to central areas, and one to the south. Here is a brief description, with some photos, to help show a little of the great variety of butterflies to be seen in a country extending 1600 km from north to south.

In March 2017 I went with my wife to Chiang Mai, in the north. For an almost all-year presence of butterflies, for accessibility and diversity, this is probably the best province in the country to start in. Just outside Chiang Mai city is the mountain Doi Suthep. Drive or take a shared taxi 15 minutes up the road to a few excellent locations near a rocky river which descends from the heights. On and around its banks many butterflies are to be found, including the White Royal, seen here drinking on the ground.

For the most renowned site in the whole country, you travel 70 km northwards (we rented a car, or you can catch a bus) to Chiang Dao. In the car park of the Wildlife Sanctuary there, you will be sure to see many butterflies of all families, including beautiful Swallowtails like the Great Windmill and the Five-Bar Swordtail. Throughout the day they imbibe the water which bubbles up onto the car park’s unpaved surface. This contains a chemical that is especially attractive to butterflies. The site is known to enthusiasts throughout Asia, and you may meet some of them here or in one of the several comfortable lodges nearby. You can happily spend a couple of days (with knee-pads) observing the butterflies at the car park or along nearby forest paths. February till April is the best time to visit, but my second visit in November 2017 was also quite productive and included the Jezebel Palmfly. You will very likely see Delias species here too, like the Red-spot Jezebel, as well as species of Troides, including the 14cm-wingspan Common Birdwing.

For the most spectacular butterfly, you need to take a travel further north to a National Park on the border with Myanmar. I did this with a friend and a guide in early April 2023. After a steep drive through the park, you hike for an hour up to the summit of the country’s second-highest mountain (Doi Pha Hom Pok, 2285m). Along the open summit ridge, you can observe the amazing Kaiser-I-Hind or Teinopalpus imperialis. A few males zip aerobatically through the air above you, sometimes coming to rest on the leaves of low magnolia trees, and if you are quick – and lucky – you will grab some photos of them basking. It is best to visit in late March or April, but Teinopalpus can be found until August. The park below the summit also holds many fine species.

After this experience, we drove back south through Chiang Mai and on for a couple of hours to explore a comfortable hiking trail beneath Thailand’s highest mountain, Doi Inthanon. It winds through lush rainforest, where we were fortunate to find a Panther (butterfly!) on a rock beside the path, as well as a few other uncommon species of Nymphalidae, including an imposing Grand Duchess. This can be a very rewarding day trip, or you can stay longer locally.

In March 2019, I took an 8-day tour with three others and our guide. We first explored protected areas around Phetchabun, roughly halfway between Chiang Mai and Bangkok. One of the highlights of this tour were the two butterflies known in English as Begums. By a small, shaded stream, we found a puddling Blue Begum. We continued with a 7-hour drive westward to Umphang, where, after a one-and-a-half-hour hike crossing a stream several times, we came to a forest clearing and caught up with a beautiful Glorious Begum, as it sucked sap from a tree trunk. In this area we also saw a skipper known as the Hieroglyphic Flat, posing for a long time on a broad leaf.

I rented a car alone and drove to Thailand’s largest National Park, Kaeng Krachan, about 200 kilometres south of Bangkok, in March 2018. I stayed there for 11 days in a local lodge. It was quite difficult to concentrate on butterflies, as there were some interesting diversions, such as primates (White-handed Gibbons and Dusky Leaf Monkeys), and birds like the imposing hornbills. Walking along the forest trails, I sometimes came across interesting sights, like when I rounded a corner to see a startled Crested Serpent Eagle abandoning its monitor lizard prey on a tree stump. Within seconds, several butterflies flew down to feed on the dead reptile. I returned to the stump a couple of hours later, and the lizard had gone.

You need to be cautious about elephants in Kaeng Krachan, but their fresh excreta are a magnet for butterflies. The main park road follows a stream where butterflies sometimes gather in large numbers. If you drive up to the ridge overlooking Myanmar, you get fine views of the unspoiled jungle around you, maybe with a passing Great Hornbill (image below).

In early July 2024, three of us plus a guide made a 13-day tour of the far south of the country, ignoring advisories not to travel to the area because of a sporadic insurgency there. We were fortunate with the weather, as it only rained extensively on two days. Starting in Nakhon Si Thammarat, we visited several parks and sanctuaries. We made five day trips from the town when we scoured for and found our first Harlequins. There are five species of this metalmark in Thailand, and in the end, we saw four of them (the fifth I’d seen previously in 2019 near Phetchabun).

These small (40 mm wingspan) beauties have a striking orange or red underside colouration and lurk in darker parts of the forest. Once found, they can be watched for some time flitting short distances from leaf to leaf. Another fine species, seen basking on tree ferns in the morning at Khao Ramrome, was the Yellow Kaiser, found in Thailand in only a few remote locations.

Heading south, for the next two days we stayed beside the Thale Ban NP, where we found a beautiful Pallid Faun. We then moved on to the southernmost area of Thailand, around Betong town on the border with Malaysia, where we spent four days exploring forest paths for rare butterflies. One of my favourites here was the Eyed Cyclops, found skulking in the low growth. The biggest surprise occurred when we were about to drive off one morning, only to find on a low leaf in the accommodation garden a fine Yellow Gorgon, resting after a rainy night. It didn’t budge, so we could shoot it at will.

On an open hilltop near Betong, our guide set up a moth tent with an MV lamp powered by a car battery. From the evening until the early morning, this drew many interesting visitors, including an elegant species of Tussar moth. On our final day, we completed our Harlequin sightings with the last of the four southern species; and the southern sub-species of Glorious Begum came down and feasted on a path for a long time.

Thailand has so much to offer the butterfly-lover. The numerous preserved areas, often with accommodation options nearby, are frequently far from the tourist traps. The country’s economy has developed very quickly, with the familiar negative results (deforestation, smog from fires, poaching, and so on), but the reserves are well controlled. A 4WD vehicle, though by no means a necessity, will get you to places few have explored for butterflies, often close to the country’s borders. Care to protect your gear from short, heavy downpours is a must, as the heavens can sometimes open almost without warning.

Over time, I have learned so much more in Thailand by having a good guide. Antonio Giudici, an Italian who has lived for over 20 years in the country and has a large, new 4WD vehicle for his tours, combines a deep knowledge of Thai butterflies with wide-ranging photography skills. The three tours described here were organized entirely by him, for a very fair price. Travelling in a group has the drawback of sometimes frightening the butterflies, so the largest size I’d recommend would be three, plus a guide. If this seems problematic because you wish to make a family trip of it, there is plenty of the usual fare to divert the children and other adults if they want a relaxing holiday – while you, of course, are out there sweating in the forest. But, at the end of the day, the beer just tastes better.

Resources

Kirton, Laurence G., Butterflies of Peninsular Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand: a pocket-sized book which serves as a handy field guide.

Ek-Amnuay, Pisuth, Butterflies of Thailand: the comprehensive reference book.

www.wingscales.com: Photo galleries of Thai species, including regular updates.

www.thaibutterflies.com: Antonio Giudici’s website, with an atlas of Thai species and details of his butterfly tours.

BugsAlive: Home (bugs-alive.blogspot.com) Blog about Thai butterflies, including descriptions and photos of the species found on Doi Suthep and elsewhere in the north.

All photographs and text copyright Michael Friel 2024.

BUTTERFLY SEASON REPORT 2024 By Jesmond Harding

Before looking at how our butterflies fared in 2024, this report will summarise the weather conditions during 2024 reported by Ireland’s meteorological service and look at the findings of a study concerning the impacts of climatic extremes on UK butterflies.

From January to December 2024 the following months had above-average rainfall: February, March, August. The following months had above-average temperatures: February, March, May, October, November, December. The following months had above-average sunshine: January, June, August and October. Seasonally, winter (December 2023, January and February 2024) was mild, with above-average rain and temperatures. Spring 2024 was mild, wet and dull. The temperature and rainfall were above average, sunshine was below average. Summer was cool and dry with variable sunshine. Autumn was mild, dry, dull. Temperatures were above average, but rainfall and sunshine were below average.

What do these conditions mean for butterflies?

A UK study by Long et al., (2017) looked at 37 years of population data gathered by the UK Butterfly Monitoring Scheme plotted against four extreme climatic events (ECEs): extreme heat, extreme cold, drought and extreme precipitation.

What did the study discover?

The percentage of species for which an extreme affected a life stage varied depending on the number of generations a butterfly produces in a year. Thus, results are presented for single-generation species (e.g. Peacock) and multi-generation species (e.g. Green-veined White) separately.

Single-generation (univoltine) Butterflies

The adult and overwintering life stages are the most sensitive for 29 univoltine species. Extreme heat during the overwintering life stage and extreme cold during the adult life stage (outside winter) are the most frequently occurring negative extreme variables both causing population declines (affecting 45% and 35% of species, respectively). Adult and overwintering life stages have opposing population responses to temperature extremes; extreme heat during the adult life stage (outside winter) causes positive population change for 21% of species, while during overwintering it is associated with negative population change in 45% of species. Another extremely important variable to which univoltine species are vulnerable is extreme precipitation during the pupal life stage affecting 28% of species. Drought appears to impact the adult stage most negatively, with 24% of the species affected but appears to be beneficial during the ovum life stage also for 24% of species.

Multi-generation (multivoltine) Butterflies

Extreme heat during overwintering and extreme precipitation during first- and

second-generation adult life stages were the factors most linked with population declines in multivoltine species (67%, 58% and 50% of all multivoltine species affected, respectively). As in univoltine species, adult and overwintering life stages have opposite population responses to temperature extremes. Extreme heat during the adult life stage outside winter is associated with positive population change in 42% of species.

Drought plays a much more important role in multivoltine species. Drought negatively affects 50% of species during their second larval life stage but has a positive impact on 25% of the species during their first egg stage.

Unlike univoltine species, multivoltine species seem to be vulnerable to extremes across all life stages: ovum, larvae, pupae, adult and overwintering. Species’ vulnerability to extremes appears to be greater in the first generation and is primarily driven by exposure to extreme heat except for the negative impacts of precipitation during the adult stage.

Generalists (widespread butterflies) were found to have more negative effects from ECEs than specialist species. The lower effects on habitat specialist might be because their habitats are in better condition than the general countryside.

Do these findings explain Ireland’s butterfly populations in 2024?

The abundance of Ireland’s butterflies during 2024 was low and extremely low in some species. While the study findings come from the UK, the low butterfly abundance experienced in Ireland occurred in the UK and Northern Europe in 2024, suggesting weather was a key influence. However, whether the conditions during 2024 meet the study’s definition of an ECE is not determined.

Looking at some common multivoltine butterflies, we saw huge declines in the Red Admiral, Small Tortoiseshell, Comma, Small Copper and Common Blue. However, Holly Blue (especially the first brood), Green-veined White, Large White and Speckled Wood appear to have held up. Habitat specialists such as Marsh Fritillary showed good numbers, but Small Blue did not.

Two univoltine butterflies that overwinter as adults, the Peacock and Brimstone, did poorly in 2024. These might have been badly affected by the warm winter weather; this may have hit the other butterflies that pass the winter as adults, the Comma and Small Tortoiseshell (both multivoltine). These outcomes reflect the findings of Long et al., (2017) regarding extreme heat during winter.

While May 2024 is described as the warmest on record, its sunshine figures were below the long-term average (LTA), with the month described by Met Éireann as ‘dull overall.’ I suspect the record warmth recorded in May may partly be related to nocturnal heat. Our summer months (June, July, August) had below-average temperatures. Thus, we had a cool summer and a warm winter. The study showed that these conditions (extreme heat during winter and extreme cold in summer) damage butterflies. The finding that high precipitation damages the pupal stage in some single-brooded butterflies might explain low figures for the Cryptic Wood White and Orange-tip; February and March 2024 had above-average rainfall.

Season Report

The flight season in Ireland runs mainly from March to October, with the highest number of species flying in June and July (Nash et al., 2012).

Unsuitable weather meant few butterflies were recorded during March. Only 58 butterflies were reported to the BCI Records Page in March 2024, but this was up on the 37 butterflies reported in March 2023 but much lower than the 308 reported in March 2022. Only 250 butterflies were reported during April, well down on the 663 butterflies reported during April 2023. Arising from the poor March conditions, the Orange-tip, and the first broods of the Green-veined White did not appear in March (except for one Green-veined White on 31st March) and the number of reports of the Orange-tip, Green-veined White and Holly Blue in April were below April 2023 figures.

Indeed, there were fewer records for all three species in 2024 compared with 2023. While May had more reports, these reflect better weather and seasonal progression. The first and last reports of these three species were Holly Blue (15 March, 14 October), Orange-tip (16 April, 10 June) and Green-veined White (31 March, 24 September). The recorded flight period for all three was shorter in 2024.

Frank Smyth provided the first report of the Large White on 31 March in Sutton, Co. Dublin. The Small White was first reported on 21 April in Sutton, County Dublin, again by Frank Smyth. The first Dingy Skipper was seen by Frank and Joan Smyth in Murvagh, Donegal, on 15 May. This is late for the first record of this butterfly; in 2020 for example, it was first observed on 25th April. However, a mid-May start date for the Dingy Skipper flight period has occurred three times since 2013; in 2013 the first report had to wait until 25 May, but 2013 had an exceptionally cool spring.

In 2024 the first Cryptic Wood White record waited until 10 May, (Jesmond Harding). The last Cryptic Wood White record in 2024 was on July 8 when Jesmond Harding and Alex Harding saw one near the car park in Brittas Bay, Co. Wicklow. The Speckled Wood was first reported on 11 April, in Howth, Dublin, by Frank Smyth while another spring and early summer butterfly, the Green Hairstreak was seen first by Eamonn Mc Glinchey at Coolboy, Donegal on 20 April.

Four of our butterflies overwinter as adults and these are the earliest to emerge in spring. The first sightings were: Brimstone (15 March, Pat Wyse), Small Tortoiseshell (10 February, Enda Flynn), Peacock (20 January, Luke and Sean Geraty), and Comma (17 March, Marie Foley).

The earliest report of an adult Marsh Fritillary was on 19 May at Lullybeg, (Jim Fitzharris) on perhaps the nicest spring day in 2024. The final record of this rarity was nearby on 3 July (Jesmond Harding). The highest number reported was 224 individuals on 8 June, on Bull Island (Sean and Luke Geraty). Other butterflies to emerge in late spring and their first emergence details are Small Copper and Wood White on 12 May (Mike Smith), Small Heath and Common Blue, on 19 May (BCI/Burrenbeo outing) all in Clooncoose Valley, Co. Clare.

Small Blue started to be observed from 16 May when Tom Kavanagh reported it from Portrane, Dublin. Only low figures of this scarce species were reported in 2024. The final report came from Maurice Simms at Sheskinmore, Donegal on 18 June.

There are few observers in the Burren particularly during the spring months so tracking the abundance and flight period of Pearl-bordered Fritillary and Wood White is difficult. There are just five reports of the Pearl-bordered Fritillary, from May 16 to June 3 while the Wood White was first reported on May 12 when Mike Smith found six in Clooncoose Valley, County Clare. No second-generation Wood White was reported in 2024. The latest record is of two seen at Knockaunroe, Burren National Park, Clare on 25 June (Jesmond Harding).

A mid-summer butterfly, the Dark Green Fritillary mainly in flight in July and August was first reported by Jesmond Harding on June 25 at Fahee North, Clare. No high abundance of this magnificent butterfly was reported in 2024. The species had its finale on August 14 at Glanlough, West Cork (report by Lisa Joy).

Although the Small Tortoiseshell flew from 10 February to 16 October, its reign was inglorious. The highest number reported was a paltry 12 on 10 May by Anthony Mooney. Previous years had higher counts of 50 plus and occasionally hundreds have been recorded on some sites, especially in late August and early September. In 2024, we received 138 reports of the Small Tortoiseshell against 325 reports in 2023.

The Peacock also produced a poor showing in 2024. Fourteen is the highest number reported at any site in 2024 (12 August, near Maynooth, Kildare). The last Peacocks reported to us in 2024 was the strangely high figure of nine individuals, eight of them sunning themselves at the edge of a Sitka Spruce plantation on Mullaghcarn Hill, Gortin Glen, near Omagh, Co. Tyrone. The Comma, flying from 17 March to 21 October was reported to us 81 times, down from 187 times in 2023.

The Silver-washed Fritillary’s 2024 flight season lasted from 16 July (first report from Michael Gray at The Raven, Wexford) to 7 September (George Mc Dermott, Ards Forest Park, Donegal). There is no report of high abundance (the highest was 9 from JFK Arboretum, 12 August, seen by Robert Donnelly).

Mid-summer is the heyday of our two golden Skippers with the Essex Skipper and Small Skipper making their debut on 16 July (The Raven seen by Michael Gray) and 8 July (Drehid Bog, Pat Wyse) respectively. Robert Donnelly counted 15 Essex Skippers at Ballyknock, Co. Kilkenny on 28 July. The closure of Drehid Bog due to the construction of the solar facility means the Small Skipper has received little attention from recorders in 2024 although an ecologist monitoring the site’s biodiversity informed BCI that the butterfly was present in good numbers during July.

How did our two tree-dwelling hairstreaks find the conditions during July and August 2024? We have seven records of Purple Hairstreak starting on July 8 when 17 were seen in Phoenix Park, Dublin by Sean Geraty. The last record was from 31 July, from the Phoenix Park, by Sean Geraty. We have no Brown Hairstreaks records in 2024. This butterfly occurs only in the West of Ireland and the good weather to encourage a trip to look for it was in short supply.

The first new summer Brimstone reported was seen on 13 July at Lullybeg. They were far less numerous than in 2023. The latest 2024 Brimstone report was made on 17 September. These records come from Lullybeg, Kildare.

Ireland’s brown butterflies are suffering declines, due to changes to grassland habitats especially on farmland and probably from atmospheric nitrogen deposition. The Meadow Brown was first noted on 26 May in Sutton, Dublin (Frank Smyth) and the final record comes from Portnoo, Donegal on 10 October (Maurice Simms). On 30 July Sean Geraty counted 908 Meadow Brown in an area of the Phoenix Park known as the 15 acres, mostly feeding on Common Ragwort. These were counted during a circular walk of the perimeter of the grassland. There must have been many more present that day, a glimpse of the abundance that can be found on high-quality, unfertilised semi-natural grassland. It is doing well in large parks where grass is allowed to grow, such as St. Catherine’s Park, Lucan, Dublin.

The Ringlet is another common brown butterfly. During 2024, its recorded flight period ran from 12 June (JFK Arboretum, Robert Donnelly) to 14 August (Maurice Simms, Rosbeg, Donegal). We had 65 reports of the Ringlet in 2024, 98 reports in 2023 and 121 reports in 2022. On 23 July Jesmond Harding counted 184 Ringlets on Lullybeg Reserve. High numbers were recorded elsewhere but in lower figures than in some previous years. Is it declining? More checks of its best habitats, tall, wild grasses in moist areas with some shade, are needed in 2025. We had 16 reports of the Grayling in 2024, all from or near coastal locations. The recorded flight of the Grayling in 2024 spanned 18 July to 11 September. The Speckled Wood is Ireland’s most recorded butterfly with 55,613 records in the National Biodiversity Database (accessed 14 January 2024). In 2024, we received 210 reports of this butterfly (294 reports in 2023) underlining how common it is in Ireland. Its recorded flight period in 2024 was 11 April to 21 October.

A declining species, the Small Heath was reported to BCI just 37 times in 2024. The number of reports of the Small Heath 2019-2023 are 54, 64, 83, 57, and 61 respectively. The highest figure recorded anywhere was 16 on Bull Island, Dublin, on 31 May. The recorded flight time was May 19 to July 13. Please keep looking for it in 2025. The Wall Brown, once distributed throughout Ireland but now in serious retreat, was reported to BCI just 18 times (34 in 2023, 32 in 2022), beginning on May 1 (Fanad, Co. Donegal, Eamonn Mc Glinchey) and finally on 1 October (Inisboffin, Co. Galway, John Lovatt). All the records are from coastal locations, highlighting its disappearance from many inland areas.

The bog butterfly, the Large Heath is rarely reported because few recorders take the plunge by traversing wet, uneven bogs in June and July. On June 19 Jesmond Harding found 18 on Drehid Bog, Kildare. We had just three reports. Another decliner is the Gatekeeper/Hedge Brown. In 2024, we obtained 25 reports (11 in 2023) ranging from 13 July (Ballydehob, Felicity Laws) to 28 August (Durrus East, Cork, Felicity Laws). The highest figure of 17 came from The Raven, 16 July, (Michael Gray).

2024 was the annus horribilis for Ireland’s butterflies. Will 2025 be their annus mirabilis? Given the low populations laid down last year, this is in doubt. However, a warm, sunny spring would help multivoltine butterflies establish positive populations to fly later in the year.

Key References

Long, O.M., Warren, R., Price, J., Brereton, T.M., Botham, M.S. & Franco, A.M.A. 2017, “Sensitivity of UK butterflies to local climatic extremes: which life stages are most at risk?”, The Journal of animal ecology, vol. 86, no. 1, pp. 108-116.

Nash, D. 2012, Ireland’s butterflies: a review, Dublin Naturalists’ Field Club, Dublin.

CRABTREE RESERVE REPORT 2024 by Jesmond Harding

| Species Recorded | Site Total 2018 | Site Total 2019 | Site Total 2020 | Site Total 2021 | Site Total 2022 | Site Total 2023 | Site Total 2024 |

| Dingy Skipper | 14 | 10 | 10 | 47 | 31 | 21 | 14 |

| Brimstone | 63 | 102 | 52 | 47 | 44 | 129 | 50 |

| Cryptic Wood White | 3 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Green-v-White | 40 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 14 | 20 | 4 |

| Orange-tip | 9 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Large White | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Small White | 26 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Green H’streak | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Common Blue | 71 | 44 | 36 | 31 | 18 | 32 | 18 |

| Holly Blue | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Small Copper | 30 | 15 | 20 | 13 | 12 | 5 | 4 |

| Red Admiral | 13 | 65 | 13 | 2 | 93 | 101 | 2 |

| Painted Lady | 77 | 260 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Small Tort | 500 | 206 | 231 | 270 | 134 | 517 | 8 |

| Peacock | 243 | 319 | 48 | 39 | 17 | 239 | 6 |

| Comma | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 11 | 0 |

| D G Fritillary | 35 | 27 | 21 | 11 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| SW Fritillary | 36 | 28 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 57 | 1 |

| Marsh Frit | 31 | 80 | 163 | 287 | 206 | 247 | 195 |

| Wall | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Speckled Wood | 51 | 35 | 11 | 7 | 19 | 22 | 11 |

| Meadow Brown | 239 | 401 | 204 | 417 | 206 | 264 | 288 |

| Ringlet | 752 | 1423 | 588 | 1097 | 636 | 1296 | 1276 |

| Small Heath | 63 | 57 | 44 | 74 | 35 | 52 | 38 |

| Large Heath | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 2298 | 3099 | 1472 | 2373 | 1514 | 3023 | 1920 |

The butterflies on Butterfly Conservation Ireland’s Crabtree Reserve at Lullybeg are counted by walking the transect route (a fixed route walk through habitats that represent those found on the reserve) on part of the reserve from April to the end of September and in October when conditions favour butterfly activity. Results are sent to the National Biodiversity Data Centre for the Irish Butterfly Monitoring Scheme. Butterflies seen outside the transect route are counted separately but the table above gives combined figures to give the site total (note: only managed areas of the site are surveyed). In 2021 and 2022, 21 counts were made, 2023, 24 counts were made; in 2024 22 counts were made. Eighteen species were seen on the reserve in 2024. The common missing species is the Large White.

The headline figure is the total number of butterflies seen and 2024 had a huge drop in abundance, 1103 butterflies short of the 2023 total! The total decline in butterflies recorded between 2023 and 2024 is 63.5%. This fall is not attributable to the two fewer visits. The decreased abundance figures are mostly due to the crash in the Small Tortoiseshell and Peacock, butterflies that can produce large populations when conditions favour them. For example, 2024 saw an abject performance in the Peacock, with a mere six counted but 239 were recorded in 2023. Brimstone fell from 129 to 50 between 2023 and 2024. The fall was noted throughout the recording period, in the spring and the new generation in the summer and early autumn. Another crash was the Silver-washed Fritillary, going from 57 in 2023 to one in 2024.

The only species to show increased abundance on the 2023 figures are the Meadow Brown (264-288) Small White (0-2) and Cryptic Wood White (0-1). These are numerically insignificant increases.

Despite these worrying declines, two conservation priorities, the Marsh Fritillary and Small Heath, in lower numbers, did not suffer the magnitude of loss seen in several others: the Marsh Fritillary fell from 247-195, and the Small Heath from 52-38.

The reserve was managed in 2024, with scrub control, with special thanks to everyone who helped and supported our work. The reserve would not be the special place it is without the care you have shown; thank you.

CONSERVATION NEWS 2024 by Jesmond Harding

This report deals with some of our work undertaken during 2024. During February 2024, the planned work party uprooted birch and willow to clear the grassland on the reserve. During the November work event, we concentrated on clearing overhanging scrub and encroaching bramble along the track in Lullymore leading to the Irish Peatland Conservation Council’s reserve. Individual members undertook some scrub clearance by hand during January and February. This made a great difference to the habitats, particularly for the Marsh Fritillary, Dingy Skipper and Brimstone.

Scrub on the broad ride through woodland connecting Lullymore and Lullybeg was also cut to ensure that the two excellent areas remain linked so that butterfly populations in the area do not become isolated. Machinery cut scrub in the southern part of the reserve and along the silt pond on the northern edge of the reserve which is used as a feeding area by butterflies. We will try to arrange grazing in 2025.

Fifty-six Marsh Fritillary larval nests were counted on the reserve in the summer and autumn of 2024. This is a big increase on the 27 Marsh Fritillary larval nests found on the reserve in August 2023. The highest figure recorded was on August 28, 2022, when 73 Marsh Fritillary larval nests were counted on the reserve, up from 65 Marsh Fritillary larval nests found in 2021 and far above the 29 nests found in September 2020. These fluctuations are normal for the Marsh Fritillary, a species known to show large variations in abundance between years, especially in response to weather conditions and parasitoids.

Our butterfly recording scheme began in 2013 and has continued. We have thousands of records on our website. These records are high quality, because they come from reliable observers and contain clear information about the species and numbers found, the date and location of the finding, and sometimes additional information about the weather conditions and habitat. New recorders frequently provide photographs of butterflies to support their record.

Our online platforms promoted conservation throughout 2024. Various blogs were written to draw attention to butterfly and moth species that may be seen at various times of the year, to conservation measures one can take to enhance gardens and public spaces for butterflies, to promote recording, to comment on findings of various reports on butterfly and moth populations and to report on Butterfly Conservation Ireland outings. Our Facebook page presents very attractive images sent in by members and by the public, as well as publicising our work/events. Conservation and habitat enhancement advice was provided to a range of bodies and members of the public.

Building support for the proposed National Peatlands Park continued during 2024. Several meetings to develop the proposal and communicate our vision were held during the past accounting year. We made a further submission to Minister Noonan and a final submission to the Draft Kildare County Development Plan 2023-2029, in April and May 2022 respectively. Butterfly Conservation Ireland produced a brochure to support the proposal (available as a PDF to anyone who wants it). Copies of this have been provided to important decision-makers and it was submitted as part of our response to the draft Kildare County Development Plan. The final Plan supports this vital, landscape-scale proposal to tackle our biodiversity crisis. This project is ongoing and has resulted in intensive engagement and planning. We hope to have some positive news on this venture in 2025.

Butterfly Conservation Ireland is a key partner in an all-Ireland initiative, involving the National Biodiversity Data Centre and Butterfly Conservation UK Northern Ireland branch to produce a butterfly atlas for Ireland 2010-2021. Several members are involved in producing species accounts for the Atlas, a reflection of the expertise within our membership. The species accounts for the Atlas have been written along with most of the other sections of the Atlas. We are now at the final stage and I expect the Atlas of Ireland’s Butterflies 2010-2021 will appear this year.

We continued to engage with the construction team working on a solar farm on Drehid Bog, County Kildare to ensure that no damage is done to the habitat used by the Small Skipper. We are happy to report healthy butterfly and moth populations have been maintained, but in the longer term, site works to control scrub are needed. BCI visited the site in June 2024.

BCI’s Val Swan and Jesmond Harding met Kildare’s biodiversity officer Meabh Boylan with other conservation groups and interested individuals in October 2024 to make submissions to develop Kildare’s Biodiversity Action Plan. We hope our input will inform the Plan’s priorities. We strongly encouraged the development of a National Peatlands Park based in north-west Kildare and East Offaly.

BCI gave a presentation at the Kildare Biodiversity Conference in October, highlighting our work. We provided native oak trees, native wildflower seeds and literature on gardening for butterflies free to attendees.

Our members have continued to work hard, organising and carrying out fundraising, recording, participating in practical conservation work and, very importantly, enjoying our butterfly and moth heritage.

Please continue your recording and conservation work in 2025; no matter how small your work may seem you can make a difference. Some man-made habitats, such as gardens, often contain more biodiversity than semi-natural habitats because of the diversity of habitats and micromanagement possible in a garden.

Finally, Butterfly Conservation Ireland thanks everyone who helped with our conservation and education work in 2025. Conservation is a battle to preserve everything good about our natural world, and we greatly appreciate your commitment to the most elegant emblems of our natural heritage, our butterflies and moths.

GARDEN SURVEY REPORT 2024 by Jesmond Harding

Introduction

Butterfly Conservation Ireland members and members of the public participate in our garden survey from March to November inclusive. The survey form, available as a download from our website www.butterflyconservation.ie and by post on request to conservation.butterfly@gmail.com asks the participant to record the first date each butterfly listed on the form was first recorded in their garden in each of the following three-month periods: March-May, June-August and September-November. In a final column, the highest number of each butterfly species seen, and the peak date are given. Finally, surveyors are asked to indicate which of the following attractants are provided in their gardens: Buddleia, butterfly nectar plants other than Buddleia and larval food plants. Twenty butterflies are listed for recording. The following report comments on the 2024 flight season, outlines the status of these butterflies in gardens during 2024, offers interpretations and comments on the findings and concludes by urging conservation and involvement in recording garden butterflies.

Abundance

Michael Gray recorded 212 individual butterflies in his garden in Rathfarnham, Dublin, during 2023 but just 105 in 2024. However, during 2024 Michael recorded 56 Holly Blue compared with 48 in 2023. My peak count for a species was a paltry five Meadow Brown and five Small Tortoiseshell on 27 June and 12 September respectively.

During the period from near the of April to the end of the count period, Marilyn Farrell found 74 Speckled Wood, 37 Small White, 33 Green-veined White and 15 Red Admiral in her garden in Lispole, County Kerry, which lies c.8km east of Dingle. Marilyn’s garden on the southern side of the Dingle peninsula is well located to benefit migrating Red Admirals. The Red Admiral had a poor year overall; I have just one in my garden.

There were some astonishingly high abundance figures for garden butterflies recorded during 2023 but 2024 saw a shocking collapse from 2023 figures. A comparator of the decline is Robert Donnelly’s butterfly census over the past two years. Robert Donnelly, whose superb garden designed for nature is in Ballyknock, County Kilkenny, counted 158 Small Tortoiseshells on August 22, 2023. In 2024 Robert’s Small Tortoiseshell population peaked at 12, recorded on 9 September 2024. None of the 17 species recorded by Robert exceeded their 2023 totals; all but two species were recorded in lower numbers. The two species that achieved their 2023 peak in Robert’s garden in 2024 were Small Copper (four was the highest seen on any day) and Painted Lady (also four). However, Robert still found four Cryptic Wood Whites on 22 June, 19 Meadow Brown on 14 July and 14 Ringlet on 25 July.

One observer, Elaine Mullins from Portmarnock, County Dublin counted every butterfly she saw during the recording period. Elaine’s beautiful suburban garden returned 142 individual Holly Blue sightings between 31 March 9 September. Although Elaine saw more Holly Blue in 2024 compared with 2023, there was no October Holly Blue for Elaine, suggesting no third brood flew there. At least two Holly Blue generations featured in Enda Flynn’s garden in Dundalk with records spanning 13 April to 8 September.

The Comma flew in Elaine’s garden between 31 March to 23 October; 79 counts of the Comma were made by Elaine during this time. Among Elaine’s records were Red Admiral (27), Painted Lady (26), Peacock (76), Small White (123) but a mere six Small Tortoiseshell. Elaine counted 507 butterflies in her garden during 2024, a healthy count in any year but especially impressive during the bleak 2024 butterfly flight season.

Pat Bell, Maynooth, commented on his experience of butterfly abundance during 2024.

This (2024) was my worst year in 13 using the same counting methodology.

I did some analysis of my top six species:

1. Small Tortoiseshell (which accounts for nearly 40% of my total abundance) – down 74% on the 12-year average

2. Red Admiral – down 72%

3. Peacock – down 40%

4. Large White – down 31%

5. Small White – down 77%

6. Holly Blue – up 22% – typical of its numbers of recent years.

It is worth recalling Pat’s experience in 2023.

I had my best year ever with a total count of 400 compared to my previous high of 352 in 2021. This was driven in particular by new highs for Small Tortoiseshell (171) and Red Admiral (68) and a second highest for Peacock (57). I also had new highs for Holly Blue (25) and Comma (10). Whites still not great – Large White average at 30 and Small White second worst at 13.

Key dates

Key dates for butterfly abundance during 2024 were very hard to determine but the first two weeks in August, especially the 8-12 August saw slightly higher abundance. The highest air temperature for August was 24.3°C recorded at Casement Aerodrome, Co Dublin (4.8°C above its long-term average (LTA)) on Sunday 11 August. This was caused by a brief high pressure that arose on August 9th and 10th giving warm, sunny weather. September 6 and 7 had warm sunny weather. The highest air temperature was 25.2°Cat Claremorris, Co. Mayo (8.4°C above its LTA) on Friday 6 September. The problem in 2024 was that no period during the summer had prolonged sunny, settled weather when populations could emerge in numbers if these were available after the cold wet months before summer. Every month from June to September was cooler than usual. Only May was warmer than usual, but this might have been mainly accounted for by night temperatures, with May being dull with all available monthly sunshine totals below their LTA. On many days not one butterfly was seen in my garden.

Number of species recorded during 2024

The number of species recorded in the gardens surveyed during 2024 was 20; in 2023 it was 18, 19 in 2022, 17 in 2021 and 2020 and 18 in 2019 and 2018. The total of 20 butterfly species is up from 15 in 2017, 14 in 2015 and 2016 and 17 in 2014. The counties represented are Cork, Kerry, Kilkenny, Donegal, Dublin, Louth, Meath, and Kildare.

Unusual garden visitors

The less common garden visitors during 2024 are Cryptic Wood White, (seen in Robert Donnelly’s garden in Kilkenny) and Silver-washed Fritillary seen in two gardens, (Robert Donnelly’s and Felicity Laws, West Cork). Another uncommon garden butterfly, the Hedge Brown/Gatekeeper, was recorded, by Felicity Laws in West Cork. Felicity’s wild garden is an extension of the semi-natural habitats in the Sheep’s Head peninsula, one of the less spoiled regions in Ireland. Felicity’s peak Hedge Brown count of four was on 13 August.

Felicity recorded this declining butterfly, a staple garden butterfly in the south of England, from 23 July to 27 August. Another two garden notables seen in 2024 are Small Heath (Felicity Laws) and Green Hairstreak, recorded by Eleanor Hort, in Donegal. Eleanor recorded this species from 2 May to 19 June, with a peak of seven on 18 May. Eleanor’s garden is c.6 km west of Ardara, surrounded by heath and bog.

How widespread butterflies featured in our gardens in 2024

The Red Admiral and Small Tortoiseshell were found in all gardens. They appear to have flown in three generations in gardens during 2024, from April to September. The Green-veined White appeared in all but one garden; the latest garden report for the Green-veined White in 2024 was on 12 September. The Large White did not perform badly in 2024 compared with 2023 with 12 seen on August 10 by Robert Donnelly; it appeared in all but one garden but in significantly lower numbers. Like the Green-veined White, it appears to have had three generations in 2024.

The Small White featured in most gardens too, but it often shies away from the more rural gardens unless brassicas are grown. Its recorded flight period in 2023 was from 18 April to 4 September. The Orange-tip has been in serious decline nationally (2008-2021: Strong decline -68%) so how well was it represented in our gardens? Happily, it occurred in all but two gardens but only one garden saw an abundance (13 on 15 May, Robert Donnelly, Kilkenny). It was recorded from 18 April to 10 June (at least, probably later).

The Common Blue was recorded in rural but not urban gardens, but it did poorly number-wise in 2024, even in the wilder places. Holly Blue featured in both rural and urban settings, especially in its favoured urban and suburban gardens, where it thrives on both native and cultivated berry-bearing shrubs. Unlike many species, its numbers held up in 2024. The Small Copper appeared in all three-month recording periods March-May, June-August and September-November in Felicity Laws’ wild garden on the Sheep’s Head peninsula in west Cork, between 19 May and 4 September. This suggests that two broods occurred in West Cork; it appears that three broods flew there in 2023. Elsewhere, it featured only in the June-August period and in fewer gardens than in 2023. The Red Admiral, Peacock and Small Tortoiseshell were ubiquitous, but Painted Lady was absent from around half the gardens, and nobody had high figures for it on any day.

The Comma’s expansion north and west is being picked up by gardeners, but it remains unrecorded in Felicity Law’s garden in west Cork or Marilyn’s garden in west Kerry. It should reach these areas if the expansion continues as expected. It was not as abundant in gardens as it was in 2023, but the 79 recorded over the season by Elaine Mullins in Portmarnock is likely the highest total. The furthest north it was recorded was in Enda Flynn’s garden in Dundalk, County Louth.

While the Speckled Wood and Meadow Brown were found in all but one and two gardens respectively the numbers varied; the male Speckled Wood is territorial so numbers in most gardens are usually low; the Meadow Brown and Ringlet are social and much more tolerant of their kind, allowing numbers to build if the habitat is sizable and suitable. Because the Meadow Brown is less specialised, occurring in open and partly shaded areas, in areas containing tall and shorter swards, it is often more numerous than the Ringlet in grassy gardens with mixed height swards. With the right mix of grassy habitats and space for both butterflies, more can be achieved. Healthy figures for Ringlets and Meadow Browns were noted by Robert Donnelly (Kilkenny). Robert also recorded a peak of eight Speckled Wood (8 and 9 September) a high figure for this butterfly. This might be explained by the size of the garden and habitat capacity. In a high-quality habitat, male Speckled Woods are likely to be more tolerant of other males or may require a smaller habitat patch.

First and the last

The earliest butterfly recorded was a Small Tortoiseshell on 27 February (Marilyn Farrell) and the last butterfly recorded was a Red Admiral in Sutton, Co. Dublin, on 30 October (Frank Smyth).

The national picture

The National Biodiversity Data Centre run a garden recording scheme very similar to ours. They wrote:

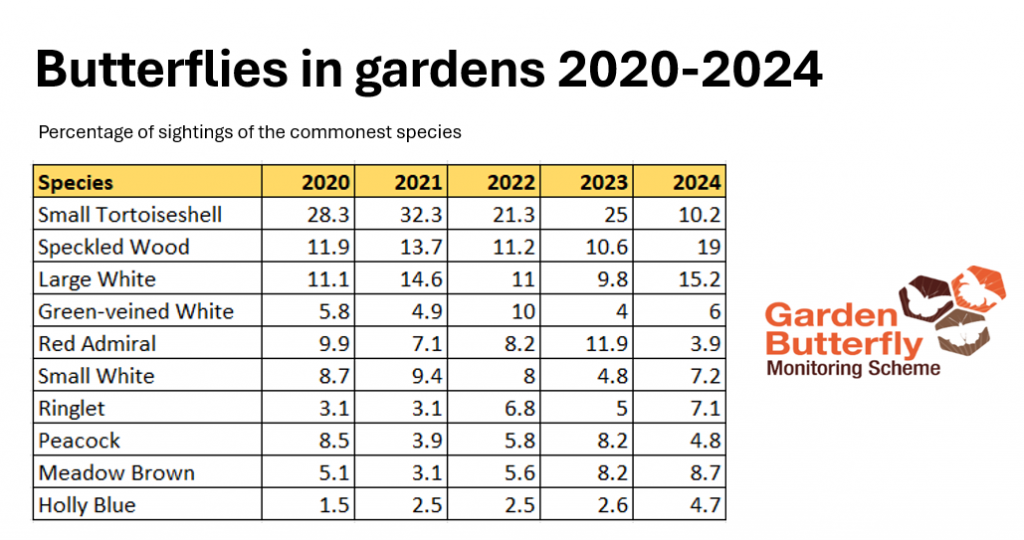

Anyone who has participated in the scheme in 2024 will know that this year was a very poor year for butterflies. The detailed analysis for the year has not yet been done but just looking at the counts of the commonest species, expressed as a percentage of all butterflies seen, shows that it was a catastrophic year for Small Tortoiseshell. In previous years Small Tortoiseshell accounted for between 21% and 32% of all the butterflies seen, but only just over 10% this year. The usual peak in numbers visiting gardens in August and September did not happen this year. It was a similar pattern for Red Admiral with fewer counted this year than any year since the scheme began in 2020.

Graphic copyright National Biodiversity Data Centre.

Graphic copyright National Biodiversity Data Centre.

Thank you

A very special thanks is due to all our garden butterfly surveyors, whose data form the basis of this report. Our gardens provide important places for our butterflies, which are only attracted to gardens that contain the resources they need. Without your help, your local butterflies might be under even more pressure than they are. Robert Donnelly and Jane Doughty from Ballyknock, Kilkenny, conserve butterflies in their extraordinary garden and send the proceeds from the sale of their garden produce to Butterfly Conservation Ireland to assist with national conservation. Robert and Jane publicise their efforts locally, and their good neighbours respond generously every year. Thank you, Jane and Robert.

GUIDE TO THE BUTTERFLIES OF THE BURREN by Jesmond Harding

The Burren region holds more butterfly and moth species than any region in Ireland. 1002 out of 1543 Lepidoptera species (butterflies and moths) have been recorded in the Burren (Nelson et al., 2024). Thirty of Ireland’s 35 butterfly species occur in the Burren (Harding, 2021).

For this guide, the Burren is the region in northwest Clare and southwest Galway predominated by karstic limestone and adjacent areas containing some karst limestone. The southeastern limit is R 31871 79852, just north of Lees Road Amenity Centre, near Ennis, County Clare. From here, the boundary extends north beyond Castletaylor, County Galway northwest to M 42788 16487, 1.5km south of Kilcolgan on the R458. From here the boundary extends west to the coast and along the coast south to Doolin at R 05789 97190.

The southern boundary which extends inland from Doolin to north of Lees Road excludes the areas of shale geology, passing north of Lisdoonvarna and south of Corofin, both County Clare. The area described consists of over 700 km2. Some of the area contains agriculturally improved grassland and valleys containing drift washed from the Burren uplands but most of the area contains exposed karst limestone and limestone grassland farmed in a low-intensity manner with light and often seasonal grazing, which maintains the habitats.

Several Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) containing limestone habitats have been designated within the Burren. These are Ardrahan Grassland SAC (M 44478 13019), Ballycullinan SAC (R 28987 86090), Ballyogan Lough SAC (R 37151 90963), Black Head-Poulsallagh Complex SAC (M 15112 06282), Caherglassaun Turlough SAC (M 40719 06142), Castletaylor Complex SAC (M 45427 15279), Coole-Garryland SAC (M 41116 03584), East Burren Complex SAC (R 32673 98291), Dromore Woods and Lough SAC (R 35152 86694), Galway Bay Complex SAC (M 36546 11099), Lough Fingall Complex SAC (M 41022 15008), Moneen Mountain SAC (M 24271 01621), Moyree River System SAC (R 38296 90058). The Aran Islands are geologically part of the Burren and are considered part of the Burren for this guide. All three islands are Special Areas of Conservation: Inisheer Island SAC (L 97451 01629), Inishmaan Island SAC (L 93411 04601), and Inishmore Island SAC (L 83976 10909).

The most important habitats for butterflies in the Burren are the habitats on karst limestone, especially orchid-rich calcareous grassland, open scrub on limestone pavement containing areas of orchid-rich calcareous grassland, wet grassland and heath, lowland hay meadows, open areas in native woodland, alkaline fens, marshes and dunes. Areas containing these habitats in proximity are often rich in butterfly diversity and abundance.

Habitat quality, mixture and extent are responsible for the high butterfly diversity. The quality is maintained by the largely unmechanised agriculture, with low fertiliser use in much of the region combined with light grazing including the use of cattle to graze uplands during winter and allowing vegetation to grow during spring and summer. Cattle create soil disturbance promoting germination of fresh plants, and their grazing develops a varying sward height ideal for butterflies like the Marsh Fritillary and Common Blue.

Scrub is controlled to maintain the priority orchid-rich grassland but over-clearing is avoided to retain the valuable scrub/orchid-rich grassland mosaics vital for the rarest butterflies, the Pearl-bordered Fritillary and Wood White.

The rocky surface and thinness of rendzina soil hinder agricultural use but this soil is rich in humus and calcium. The soils support many sensitive plants including nectar plants for adult butterflies and foodplants for the caterpillars. As well as contributing to the development of rendzina soil, limestone rock creates a warm micro-climate vital for the development of butterfly and moth caterpillars. The regular rainfall ensures plants remain in good condition while the porosity of the carboniferous limestone prevents damp conditions from developing which is vitally important for our scarcest species, especially Wood White and Pearl-bordered Fritillary, as well as for more widespread butterflies like Dingy Skipper, Wall Brown and Grayling. Their caterpillars need succulent food in dry, warm conditions, which are ecological needs not met in much of the countryside beyond the region.

In parts of the Burren, especially on lower land in the eastern and central areas, habitats occur in intimate mosaics, adding to the botanic diversity, and insect richness. Habitats such as orchid-rich calcareous grassland, wet grassland, scrub, dry limestone heath, and limestone pavement frequently occur in intimate proximity, making it hard for ecologists to assign such zones to a particular habitat category, but create ecological conditions that are the richest in Ireland. The wide availability of such habitats and the large extent of the Burren allows butterflies and other animals to move throughout the region, to take advantage of the habitats that are in the best condition.

This ensures that populations do not become isolated, which is very important because it means that a butterfly population does not become adapted to remaining in small areas where it is more vulnerable to extinction due to chance events such as severe flooding, drought or other sustained unsuitable weather conditions. It has been observed that some butterfly species that have become highly reluctant to fly away from their birthplaces in small nature reserves in England, such as the Pearl-bordered Fritillary and Wood White, are much more mobile in the Burren. This shows the Burren region continues to provide excellent conditions at landscape scale for the rarest species.

Five of the six Threatened Irish butterflies and four of the five Near Threatened species, are found in the Burren (Regan et al., 2010). Some of these, such as the Dark Green Fritillary, occur in great abundance in the region. More common species, such as the Brimstone, Meadow Brown and Ringlet, occur in high numbers in most years.

The great variety of flora and its abundance supports these high populations. Plants that feed the caterpillars include Common Dog-violet, Common Bird’s-foot-trefoil, Cuckooflower, Bitter-Vetch, Tufted Vetch, Meadow Vetchling, Kidney Vetch, Common Nettle, Devil’s-bit Scabious, Common Sorrel, Sheep’s Sorrel, Oak, probably Sessile Oak, Common Buckthorn, Alder Buckthorn, Common Blackthorn, Common Holly, Red Fescue, Wood Brome, Cock’s-foot Grass, Purple Moor-grass. Adult butterflies use some of these plants as nectar sources, as well as Common Knapweed, Greater Knapweed, Wild Thyme, Common Spotted Orchid, Pyramidal Orchid, Bloody Crane’s-bill, Red Clover, Common Hawthorn, Primrose, Meadow Thistle, and other thistles.

This guide shows all the butterflies that occur in The Burren. The Aran Islands hold 21 species, lacking the woodland and scrub species because of the extreme scarcity of woodland on the islands.

The Burren has 27 resident and three regular migrant butterflies. Dingy Skipper and Grayling exist as distinct subspecies unique to The Burren. In recent decades there have been declines in many species in the rest of Ireland. The data from the Burren is insufficient to determine if declines have occurred in the region. Population trend data comes from the National Biodiversity Data Centre. ‘Uncertain’ means the population trend is unclear; ‘Unknown’ means data is lacking, and migrants are not rated. Flight periods vary according to seasonal conditions, altitude, latitude and site characteristics.

Descriptions of appearance refer to the upper surfaces of wings unless the undersides are specifically described. “Sexes alike” refers to appearance. “Sexes similar” indicates that small differences exist.

T= Trend in population abundance H=Habitat Fl=Flight period Fp=Larval foodplant

SKIPPER

Dingy Skipper: Variegated grey and brown. The paler Burren form is described as a subspecies: Erynnis tages baynesi; skipping flight. Sexes alike. T: Uncertain, but common in Burren. H: Mainly grassland/limestone pavement, quarries. Fl: April-June. Fp: Common Bird’s-foot-trefoil, possibly Greater Bird’s-foot-trefoil in damp areas.

WHITES

Wood White: Weak, low flight. Sexes alike. Two generations. T: Uncertain. H: Open scrub on limestone. Fl: May-June, July-August. Fp: Tufted Vetch, Bitter Vetch, Meadow Vetchling, probably Common Bird’s-foot-trefoil.

Clouded Yellow: Migrant. Mustard coloured: black forewing margins spotted in female; undersides alike; whitish-grey female form occurs. H: Grassland. Fl: April-October. Fp: Common Bird’s-foot-trefoil, clovers, etc.

Brimstone: Male daffodil yellow, female paler, almost white. T: Uncertain. H: Woods, scrub. Fl: March-June, July-September, then overwintering until March. Fp: Purging Buckthorn and Alder Buckthorn.

Large White: Female has two forewing spots; male lacks these; has a broad black wingtip; undersides alike. T: Declining. H: Wide range, including gardens. Fl: April-June, July-September, October. Fp: Cabbage family.

Small White: Looks like a small Large White but the uppersides are milky white, not bright white as the Large White. Female has two forewing spots; male has one. T: Declining. H, Fl, Fp: See Large White.

Green-veined White: wing veins marked with dark scales, especially undersides; male: one forewing spot, female: two. T: Declining. H: Damp areas, ditches. Fl: April-June, July-September. Fp: Cuckoo Flower, Watercress, etc.

Orange-tip: The female is white with black wingtips; she lacks the male’s extended orange wingtips. Hindwing underside has a mottled pattern in both sexes. T: Declining; in The Burren, it occurs on wet grassland and marshes and in wooded areas containing damp rides and clearings. H/Fp: As above, wood edges. Fl: April-June.

HAIRSTREAKS AND COPPER

Green Hairstreak: Small, settles with closed wings, upper surfaces brown; undersides green with white streak; sexes alike. T: Unknown, but very rare in The Burren; known from Ballindereen. H: Wet heaths, wet coastal grassland. Fl: April-July. Fp: Gorse, Bilberry, Common Bird’s-foot-trefoil, possibly Purging Buckthorn and Alder Buckthorn, vetches.

Brown Hairstreak: Male lacks broad orange forewing patches; otherwise, sexes alike. T: Unknown. H: hedges, scrub, chiefly in the Burren, with outlying populations in karst areas outside The Burren in Galway and Mayo and one away from limestone in west Tipperary. Fl: July-September. Fp: Common Blackthorn.

Purple Hairstreak: Male’s purple visible only in sunlight; female’s purple always visible; undersides silver-grey. T: Unknown; scarce in the Burren; known from Garryland and Ballyeighter Woods. H: Deciduous and mixed woodland containing oak. Fl: July-August. Fp: Native oaks.

Small Copper: Highly active. Sexes alike. H: Grassland. Fl: May-June, July-August, September, occasionally October. T: Declining. Fp: Sheep’s Sorrel, Common Sorrel.

BLUES

Small Blue: Tiny and easily overlooked. Male only has dusting of blue. T: Declining; commoner between Poulsallagh and Black Head. H: Limestone grassland with scrub; occurs in small numbers in areas with low swards containing the foodplant. Highly vulnerable to overgrazing. Fl: May-early July Fp: Kidney Vetch.

Common Blue: Male blue; female variable amounts of blue and brown with orange markings near the edge of the forewings. T: Declining. H: Grassland. Fl: May-June, August-September, early October. Fp: Trefoils, clovers.

Holly Blue: Male all violet, female violet with black forewing tips/edges. T: Increasing. H: Woods, scrub, hedges. Fl: April-June, July-September, occasionally October. Fp: Holly, Alder Buckthorn in spring, Ivy in summer/autumn.

VANESSIDS AND FRITILLARIES

Red Admiral: Powerful migrant. Sexes alike. H: Wide range, anywhere flowers and nettles occur. Fl: April-November, especially August and September. Fp: Common Nettle.

Painted Lady: Powerful migrant. Sexes alike. H: Wide range, anywhere flowers and thistles occur. Fl: Mainly June-September. Fp: Marsh Thistle, Spear Thistle, and Creeping Thistle, etc.

Small Tortoiseshell: Familiar garden visitor. Sexes alike. Overwinters as adult. T: Declining. H: Wide range. Fl: March-early June, July, late August-September then overwintering until March. Fp: Common Nettle.

Peacock: Beautiful; powerful flier. Undersides black. Sexes alike. Overwinters as adult. T: Stable. H: Woods, scrub. Fl: Late March-June, July-early September then overwintering until March. Fp: Common Nettle.

Comma: Ragged edges distinctive. Sexes similar. Overwinters as adult. T: Increasing. H: Woods. Fl: March-June, July-August, late September-October, overwintering until March. Fp: Common Nettle, Wych Elm.

Pearl-bordered Fritillary: Deep orange, black markings; named for underside pearl markings along hindwing margin. Sexes alike. T: Uncertain. H: Open, sunlit, sheltered scrub on limestone. Fl: Late April-June. Fp: Violets.

Dark Green Fritillary: Dramatic flier. Female larger, darker, more rounded forewing. T: Uncertain. H: Flower rich limestone grassland, vegetated dunes, grassy woodland clearings, open scrub. Fl: June-August. Fp: Violets.

Silver-washed Fritillary: Our largest butterfly. Graceful flight. Female darker, is spotted and lacks male’s forewing bars. T: Uncertain. H: Woodland, open, mature scrub. Fl: Late June-early September. Fp: Violets.

Marsh Fritillary: Low flier with distinctive chequered pattern. Basks often. Sexes alike but the male is smaller and body thinner. T: Uncertain. H: Grassland rich in larval foodplant. Fl: May-early July. Fp: Devil’s-bit Scabious.

BROWNS

Speckled Wood: Chocolate brown with cream speckles. Sexes similar. T: Declining. H: Woods, scrub, hedges, lanes. FI: April-October. Fp: Grasses, e.g. Cock’s-foot, Yorkshire Fog, False Brome.

Wall Brown: Sun-lover. Male darker with a diagonal brown band across forewing. H: Limestone grassland, rocky places, green roads, dunes. T: Declining, endangered. Fl: May-June, August, occasionally late September-early October. Fp: Fescue grasses, Cock’s-foot, Yorkshire Fog, False Brome.

Grayling: Hides well, closes wings on landing; paler Burren form is known as subspecies: Hipparchia semele clarensis. Sexes similar. T: Declining. H: As above. Fl: July-September. Fp: Marram, fescue grasses, Blue Moor-grass when the larva is larger.

Meadow Brown: Sexes similar but female with more orange on the forewing. T: Declining. H: Grassland. Fl: June-October; flies later in the west Burren. Fp: Grasses, probably favouring fescues, Annual Meadow Grass, Smooth Meadow Grass.

Ringlet: Dark chocolate-coloured forewings. Sexes alike. T: Declining. H: Damp, tall, usually partly shaded grassland. Fl: June-August. Fp: Grasses e.g. Cock’s-foot, Yorkshire Fog, Purple Moor-grass.

Small Heath: A bright butterfly with bobbing flight, sexes similar, settles with closed wings. T: Declining. H: Grassland, usually well drained. Fl: May-August. Fp: Fine-leaved grasses, especially fescues containing leaf litter.

Note: All photos for this guide were taken in the Burren.

Key References

Harding, J.M., 2021. The Irish Butterfly Book A Complete Guide to the Butterflies of Ireland. Privately published, Maynooth.

Regan, E.C., Nelson, B., Aldwell, B., Bertrand, C., Bond, K., Harding, J., Nash, D., Nixon, D., & Wilson, C.J. (2010) Ireland Red List No. 4 – Butterflies. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Ireland.

Nelson, B., O’Donnell, M., Bond, K.G.M., O’Connor, A., Marnell, F. Cotter, S. (2024) ‘CHECKLIST OF THE BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA) OF THE BURREN REGION OF WESTERN IRELAND’, Entomologists’ Record and Journal of Variation. Edited by C.W. Plant, Volume 136 ((Part 5 Supplement)).

THE MYSTERIOUS WORLD OF THE WOOD WHITES by Jesmond Harding

Introduction

For years, butterfly observers have wondered why the Wood White, Leptidea sinapis, is common in Ireland in open, even unwooded, habitats, while in Britain it is rare and confined to specific woodland and scrubland habitats. In 2000, Maurice Hughes and Brian Nelson who carried out genitalic measurements of specimens at the Ulster Museum went some way to explaining the mystery; there are two wood whites in Ireland. The ‘new’ species is the one found in most of Ireland, while the Wood White Leptidea sinapis occurs only in limestone areas in Counties Clare and Galway. In 2000, this new species was thought to be Réal’s Wood White Leptidea réali, a species unknown in Britain, but known in France.

However, a study published in 2011 that used genetic techniques and genitalic measurements discovered a new species, the Cryptic Wood White Leptidea juvernica, which appears identical to the Wood White Leptidea sinapis and Réal’s Wood White (Dincă, V. et al., 2011). This study also discovered that the wood white that is widespread in Ireland is the Cryptic Wood White. Réal’s Wood White has not been found in Ireland. The Cryptic Wood White can be separated from the Wood White based on examination of the genitalia. However, the Cryptic Wood White cannot be separated from the Réal’s Wood White based on appearance or genitalia.

This explains the initial identification in 2000 of the then-unknown Cryptic Wood White as Réal’s Wood White, but the genetic analysis results published in 2011 has shown the Cryptic Wood White to have a much higher chromosome count than Réal’s Wood White (80, 82, 84 compared with 52, 53, 54) and a higher chromosome range. All three wood white species look identical in the field. However, the Cryptic Wood White is apparently fully synmorphic (identical) to Réal’s Wood White (although genetically distinct) explaining why it remained unnoticed for such a long time despite intensive research (Dincă, V. et al., 2011).

Description

Ireland’s wood whites (Wood White and Cryptic Wood White) have a wingspan of about 42mm. Both species and sexes have spot-free, milky white uppersides and black wing-tips, which are darker, more defined and slightly more extensive in the male. Both sexes have darker undersides with the hindwings, wing-tips and base of the costa suffused with a greenish tinge. The sexes look similar, but the male has a conspicuous white spot on the antenna club, which is brown in the female. Another feature distinguishing the sexes is that the female has a rounder forewing tip (apex). Both wood white species always settle with closed wings. In male Wood Whites of the second generation, the black wing-tips on the forewing uppersides are smaller but darker, while in the female the dark markings on the wing-tips are paler in the second generation and are often just a light grey smudge. The undersides are also paler in the second brood.

Differences

While the two species look identical in all life stages, use the same plants for their caterpillars and adult feeding, there are some differences to separate them. Our two wood whites (Leptidea butterflies) differ in their brood structure. In Ireland, apart from a single example (Harding, 2021), the Cryptic Wood White does not fly in a second generation while the Wood White does; the Wood White flies from May to late June or early July, while the much less numerous second generation flies in late July to mid-August. The second brood of the Wood White is a partial brood with most of the pupae formed by the spring generation’s offspring overwintering until the following spring.

The Wood White is tied to warm, dry breeding sites on exposed carboniferous limestone in County Clare and County Galway, especially the Burren. The Wood White does not breed on open grassland in Ireland, only in areas in scrub and woodland on limestone that receive abundant sunlight but with some shade. The Cryptic Wood White breeds in damp, humid grassland, both in open, well-developed semi-natural herb-rich grassland and in tall, unshaded herb-rich grassland adjoining scrub and woodland. The Cryptic Wood White does not occur in the Burren but occurs throughout Ireland in suitable habitats.

Individual butterflies wander, and this might account for the occasional finding of a Cryptic Wood White near or in areas known to be occupied by the Wood White. This has been noted in Merlin Park, Galway and Dromore Wood, Clare. Follow-up searches in Dromore did not find the two species overlapping, reaffirming the finding that these species are allopatric (occurring in separate non-overlapping geographical areas).

Mate Identification

However, what would happen if a virgin female met a male of another wood white species?

Interestingly, this has happened in the wild and the laboratory. Before I go further, I need to describe the courtship process.

When a male encounters a female, a remarkable courtship takes place. The courtship ritual occurs with the settled pair face to face. The male unrolls his proboscis and waving his head from side to side, strikes the female on the edge of each hindwing, alternately. The male Wood White will then engage in wing clapping. This distinguishes this species from the Cryptic Wood White, as the male of that species does not perform this wing-clapping ritual. However, wing clapping is not especially conspicuous. A receptive female bends her abdomen towards his and joining occurs. Mating lasts around 30 minutes.

Females often refuse to mate, probably because they have mated already, but the male’s courtship ritual continues, often for over 15 minutes. Although the unwilling females of both wood white species flick their wings at males, this is not interpreted by males as a rejection signal. Eventually, the male departs, but he often returns to the still-settled female and resumes his efforts. Why this waste of energy by the male and of egg-laying time by the female should occur is hard to interpret; it must reduce survival rates and breeding success. Frequently, when mating has been completed and the pair separate, the male quickly returns and attempts to mate with the same female again, and the courtship ritual is repeated, but mating is not.

In Finland, the Cryptic Wood White encounters the Wood White where open grasslands adjoin woodland. In Finland and Poland, the Cryptic Wood White is expanding its distribution while the Wood White is declining. In Poland, the Cryptic Wood White is replacing the Wood White. The different ecological requirements of the two species are likely related to this change. Due to their different ecological preferences, it has been assumed that opposing population trends in these species are related to anthropogenic (man-made) habitat changes rather than direct competition between them. The observations of those involved in a Finnish study (Lehtonen et al., 2017) are congruent with this view; they only observed Cryptic Wood White in heavily modified open habitats, but most Wood Whites were observed in forested landscapes. It therefore seems likely that Cryptic Wood White benefits from anthropogenic disturbance, possibly at the expense of Wood White. Population trends and habitat selection in these species may also be driven by courtship pressure on less abundant species (Friberg et al., 2008c, 2013). The current situation in southern Finland provides an excellent opportunity to study the factors and possible interactions causing the opposite population trends in these two species.

Only females recognise mates

Male Cryptic Wood Whites and Wood Whites court females of both species. This suggests that males do not recognise conspecific females (their own species) or heterospecific females (not their species). However, females recognise conspecific males. To my knowledge, the basis of female discernment in these species has not been discovered. Male Wood Whites and male Réal’s Wood Whites do not recognise each other’s females. Friberg et al., (2008) found the lack of clear-cut between-species differences further explains the lack of male species recognition, and the overall similarity might have caused the long-lasting elaborate courtships, if females need prolonged male courtships to distinguish between conspecific and heterospecific suitors.

In the Freiberg study, conducted in 2004 and 2005, in which male Wood Whites and Réal’s Wood Whites courted females of their own species and the other wood white females, no female accepted a mate that was not her species, in the laboratory or the wild. In the wild, the experiment was carried out where both these wood white species occur together and fly at the same time. Interestingly, virgin females of both species rejected courtship by conspecific males. In the laboratory experiments, Réal’s Wood White females courted by conspecific males accepted mating in 16 of 26 cases (62%) and 18 of 29 (62%) Wood White courtships ended with female acceptance. Some males failed to impress the ladies!

The males of both wood whites, unlike the females, were not able to recognise their species. The time it took for males to recognise refusal and end courtship was measured. On average, male Wood Whites gave up after 4 minutes 48 seconds. This was regardless of whether he courted a female Wood White or a female Réal’s Wood White. Male Réal’s Wood Whites spent longer courting female Wood Whites before giving up than they did courting their females.

No female Wood White waited for longer than 230 seconds before accepting a mate, but four out of 16 female Réal’s Wood Whites waited for longer than the longest Wood White courtship before accepting a mate; one male Réal’s Wood White displayed for almost 12 minutes (593 seconds) before mating occurred. However, about 13 of 18 Wood White females (72%) and 7 of 16 Real’s Wood White females (44%) accepted mating after less than 20 seconds of male courtship. These swift acceptances tally with my observations of female acceptance in white butterflies. I have not seen a lengthy courtship in any white butterfly, including in the Wood White and Cryptic Wood White, that resulted in mating.

In the wild, 13 of 24 Réal’s Wood White interactions (54%) and 9 of 12 Wood White interactions (75%) led to mating, while none of the 16 occasions of Réal’s Wood White males courting Wood White females or the ten courtship interactions between Wood White males and Réal’s Wood White females ended in mating. There was no difference in male giving-up time between con- and heterospecific courtships for males of either species. No difference in time to female acceptance could be detected between the two species in the field experiment.

How do females recognise their males?

Butterflies usually recognise conspecifics by their appearance, at least when initially approaching or being approached by a potential mate but how is recognition achieved when appearance is identical or near identical? The Friberg study measured UV reflectance in the wings but found no significant difference in white areas. Only one difference was noted: the apical black patch on the forewing upperside is darker in the Réal’s Wood White (and Cryptic Wood White). This difference is between males and females and between species. However, is this important for species recognition, given courtship occurs with closed wings in Réal’s Wood White? The study concludes that colour difference is not important for females in mate recognition.

Chemicals emitted during courtship to signal presence, species and sex identity and willingness to mate are important in reproduction. The study analysed the chemicals emitted. The composition of the volatile cocktail (range of chemicals emitted into the air) varied between the different species and sexes. All females, of both species, emitted ocimene, a volatile that was not emitted by males of either species. Limonene and methyl salicylate were present in the chemical cocktails of all butterflies, and all individuals tested, except one Réal’s male, emitted octyl alcohol. Two compounds were unique to Wood White; five of 10 females (50%) and 10 of 21 males (48%) emitted dihydroisophorone, and the same 15 individuals also emitted cyclonol. The significance of these findings is described under Chemical signalling below.

Antennal morphology

Because males wave antennae during courtship and both sexes are face to face, differences in antennae might be cues to recognition. Wood White individuals of both sexes had a higher number of light brown segments on the outermost tips of the antennae than Réal Wood White (and Cryptic Wood White) individuals. In both species, the white patch on the antennal club is larger in the male than in the female. No significant difference in white patch size was found between the males and females of the two species. The investigators conclude that patch size was unlikely to serve as a species-determining cue.

Wing-clapping