BUTTERFLY CONSERVATION IRELAND ANNUAL REPORT 2021

Common Blue mariscolore form Photo J. Harding.

Common Blue mariscolore form Photo J. Harding.

CONTENTS

• Introduction

• Butterfly Isle

• Butterfly Season Report

• Events Report

• Crabtree Nature Reserve Report

• Conservation News

• Garden Survey Report

• Butterfly Atlas in Kildare

• Habitat Special: How Important are Hedgerows for Butterflies and Moths?

• Introducing Ireland’s Hawkmoths

INTRODUCTION

Dear Butterfly Conservation Ireland Member,

Welcome to Butterfly Conservation Ireland’s Annual Report 2021. 2021 had beautiful dry, sunny weather in March and April, but May was very wet and cold. June was much improved, and the second half of July was hot, sunny and dry. Unusually August was cooler than July and much wetter. September was a pleasant, warm month but frequently overcast while October was mild but wet. Accordingly, we saw consistent reports of butterfly activity during early and mid-spring but lower than expected numbers in May and generally later start dates for the first appearance of some species. The summer was generally good, apart from the first half of July and the first three weeks in August. Our reserves performed very well thanks to your support and hard work put in by our volunteers and friends. Our small staff are fortunate in having excellent support from our active membership whenever help is needed in these endeavours. Butterfly Conservation Ireland’s membership grew again, reflecting perhaps the growing concern for the environment and owing to the increased interest in nature that has arisen under the coronavirus pandemic restrictions on movement and as a response to the global biodiversity crisis.

Your continued practical and financial support is greatly appreciated as we strive to ensure that our butterflies and moths continue to have an important voice for their conservation. We pursue the conservation agenda at every opportunity with many submissions to government bodies and other organisations concerning our habitats. Our recording scheme continues to provide important quantitative and qualitative data; this should prove very important for The Atlas of Butterflies in Ireland, 2017-2021, publication of which is planned for 2023. This data will feed into the revision of the Red List of Ireland’s butterflies so keep the records coming in 2022. Our financial accounts were approved thanks are due to our joint treasurers Michael Jacob and Joseph Harding. Thanks are due to Richella Duggan who looks after our social media platform and to all who contributed to this report’s contents and to all our members and supporters. We hope that you enjoy reading our Annual Report and we look forward to hearing from you in 2022.

Jesmond Harding (Secretary)

Butterfly Conservation Ireland

Butterfly House

Pagestown

Maynooth

County Kildare

Butterfly Isle

One lovely challenge one might set oneself is to see all of Ireland’s butterfly species in one year. Patrick Barkham, a journalist who writes for The Guardian, embarked on this task in the UK and published his experiences in The Butterfly Isles in 2010. Patrick had 60 species to find and managed all 60 in 2009. The smaller species tally in Ireland makes for a more modest challenge, but Patrick did not have to reckon with the travel restrictions and the more erratic weather we have in Ireland. In this article, our own Jim Fitzharris describes his efforts to find all our species in 2021.

Male Holly Blue with wings held widely apart, a rare sight in this lovely butterfly (Knocklyon, County Dublin, 23 April 2021).

Male Holly Blue with wings held widely apart, a rare sight in this lovely butterfly (Knocklyon, County Dublin, 23 April 2021).

In 2021, I set out on a mission to see all 35 of the regular Irish butterfly species in a calendar year. The small Irish list does have the advantage of making this quest quite feasible. It has been done before: I am aware of at least three people who have managed to do it in recent years.

I am primarily a birdwatcher (or birder as they are now called). Like many birders, I took more than a passing interest in other aspects of natural history over the years, especially wildflowers, mammals and butterflies.

My first task was to complete my Irish butterfly list. In late 2018, I sat down and worked out how many species I had seen: it was only 22 of the regular species, despite travelling the length and breadth of Ireland birding. Thus, I had plenty of work to do to see the missing 13 species! In 2019, I notched up Essex Skipper, Purple Hairstreak and Comma although overall, my efforts were desultory that year.

I made a much more determined effort in 2020 and, although hamstrung by Covid-related travel restrictions, I managed to see another new six species: Small Skipper, Cryptic Wood White, Brown Hairstreak, Small Blue, Marsh Fritillary, and Gatekeeper.

Female Gatekeeper/Hedge Brown basking on bramble (Raven Wood, County Wexford, 16 July 2021).

Female Gatekeeper/Hedge Brown basking on bramble (Raven Wood, County Wexford, 16 July 2021).

2020 was also meant to be the year of my attempt at the “Grand Slam” but this was not possible due to the travel restrictions. I did manage to see 30 species that year. I was still missing four butterflies that I had never seen: Dingy Skipper, Wood White, Pearl‑bordered Fritillary and Large Heath. Apart from these, the only other one I missed in 2020 was Wall which eluded me despite some extensive searches in south Wexford and elsewhere.

So, we come to 2021 and once again I made serious plans to attempt this quest.

Broadly speaking, butterflies can be divided into two groups: generalists and specialists. The generalists occur in a variety of habitats and many have long or multiple flight seasons. None of these species requires a special effort to see them: frequent field trips in various habitats should yield them all. Examples include most of the Whites and Blues, and the vanessids such as the Red Admiral, Painted Lady and Small Tortoiseshell.

The specialists are either locally distributed and/or quite habitat-specific, and often have just single broods with resultant relatively short flight seasons. Examples include the skippers, the hairstreaks, most of the fritillaries, the Burren specialities and some nymphalids which nowadays includes the Browns. To see these species requires good knowledge of their distribution and flight seasons, as well as the ability to move quickly to avail of a good day weather-wise when they are on the wing.

Some species do not fall readily into either category; examples include Small Copper, Silver‑washed Fritillary, Wall and Small Heath, widespread but with specific habitat requirements.

Everyone knows that the key months for butterflies are in the late spring and summer. That said, from early in the year I was on the lookout for my first butterflies. All would agree that there is nothing quite like that first glimpse of a butterfly in late winter or early spring to lift the spirits and act as a harbinger of summer.

In late February, I saw a Small Tortoiseshell on a sunny day at Rosslare Harbour, Wexford so the campaign was under way! March added only Holly Blue in the garden so a slow start, but not unexpected.

April brought the tally to ten with the addition of Small White, Comma (nice to see one of these early on), Green-veined White, Peacock, Orange-tip (a classic spring species), Red Admiral, Large White and Speckled Wood: all expected generalists.

May is an important month in the butterfly calendar because many species emerge this month and it is a key month for some of the specialists, especially those that occur only in the Burren.

Weather is key for a successfully butterfly field trip and early May was disappointing with less‑than‑ideal weather. A mid-month trip to Ballyteigue Burrow in south Wexford produced Small Copper and Small Blue: two bright, colourful, summer sprites that always gladden the heart.

Male Brimstone feeding on Common Bird’s-foot-trefoil (Lullymore, County Kildare, 27 May 2021).

Male Brimstone feeding on Common Bird’s-foot-trefoil (Lullymore, County Kildare, 27 May 2021).

I monitored the BCI website and Facebook regularly to see what species had emerged. I pored anxiously over weather maps and scrutinised weather apps, and finally, on a bright, sunny Sunday, I made my first long-distance foray to the Burren. Early morning saw me walking down the legendary Clooncoose Valley praying for sun and warmth to entice the butterflies to spread their wings! Almost on cue, my first ever Pearl-bordered Fritillaries must have sensed my anxiety as a couple suddenly zipped past but one sympathetic individual settled to give me a nice view. It was soon joined by my first Wood Whites who were much more leisurely. Things were looking up! I continued to the Gortlecka area where it was now quite hot and sunny – ideal conditions. The butterflies did not disappoint, with my first Dingy Skippers appearing, followed by Wall and lovely Brimstones. As I wended my way back up the valley that afternoon, I saw more Pearl-bordered Fritillaries and Wood Whites and arrived back at the car hot and tired, but well satisfied with my day. This was the high point of the year!

Later in the month, I paid a quick visit to Portrane in Dublin to see Small Blue and Small Heath while a trip to the legendary Lullymore in Kildare yielded Cryptic Wood White and Marsh Fritillary against a backdrop of Dingy Skippers and some nice Brimstones. The tally for the year now stood at 21 – 60% of the total, illustrating just how important May is.

June is not as critical as May but it was important to maintain momentum and Green Hairstreak is a must this month. I had looked in vain at a couple of sites but finally caught up with them at Mount Lucas in Offaly.

The other key species this month was Large Heath and I connected very well with them at Drehid Bog in mid-June. At least I had now seen all 35 regular species in Ireland! I also saw Painted Lady, Meadow Brown, Ringlet and Dark Green Fritillary in June, the last at beautiful Ballyteigue in County Wexford, thus bringing the year’s tally to 27.

Female Brown Hairstreak on bramble (Tulla, County Clare, 15 August 2021).

Female Brown Hairstreak on bramble (Tulla, County Clare, 15 August 2021).

Now to July, another important month for the later emerging butterflies. The weather early on did not play ball, but by the middle of the month the right conditions occurred. It was time to make hay! A busy few days followed: after seeing Silver-washed Fritillary in Knocksink, Wicklow, I went to Drehid Bog, Kildare the next day and saw Small Skipper at this classic site. Then I went to Wexford for a few days. First up was the wonderful Raven Wood where I saw some nice Gatekeepers and a range of other species. The next trip was to Tacumshin Lake, a very reliable spot for Essex Skipper, and then a lovely day at Ballyteigue seeing many lovely butterflies at this superb site, albeit nothing new for the year. Finally, I saw Purple Hairstreak in the Phoenix Park high on oak trees later in the month – the total for the year was now 32.

I had some good trips in early August but nowt new. A quick visit to Howth in mid-month produced a nice bonus Grayling. Then another Burren pilgrimage beckoned and I risked travelling west on a dull, cool day. My faith was rewarded with a later spell of warm sunshine and I managed to see 13 species in one quiet bushy lane, the highlight being the very local and attractive Brown Hairstreak. I was now at 34 for the year and the only target species that remained was Clouded Yellow. So far, 2021 had been a very poor year for this somewhat elusive, migratory species.

My birding takes me to south Wexford a lot in the autumn but repeated visits to the southeast coast drew a blank. The year drifted into September and, although I had many enjoyable days in the field, the much‑needed southerly winds did not materialise. In October, I went to Cape Clear in Cork for my customary, autumn birding holiday. This was last chance gulch! The first day was damp and grey but the next day brought the start of a late Indian summer. Several observers saw Clouded Yellows but not yours truly! They just eluded me all day despite a total of 10+ being seen – always just “around the corner”. The next day, the weather was still fine: after trekking around the south of the island, a fellow birder called out to me: “Clouded Yellow!” It took me a few seconds to latch onto it but there it was: dancing along, a truly tropical burst of yellow, orange and black. Bingo! I later saw another three that day when 20+ were seen in total on the island.

Male Marsh Fritillary (Lullymore, County Kildare, 27 May 2021).

Male Marsh Fritillary (Lullymore, County Kildare, 27 May 2021).

So, my mission was finally accomplished – what a relief! Many might think that this was a mindless “ticking” exercise. Yes, maybe to some extent it was, but I went to many sites that were new to me, revelled in all the butterflies that I saw as well as the other wildlife on show, especially dragonflies & damselflies and moths, not to mention the usual birds and the magnificent Burren flora which I had not experienced for decades. I did not have one “bad” day: a trip to Lullymore and Timahoe on a cool breezy day in early May did not yield a single butterfly but I still saw a lovely Pine Marten at Lullybeg which was a fine compensation.

I dutifully recorded every single butterfly sighting (and other species) with the NBDC (well over 500 individual butterfly records alone) and sent all the better observations to BCI as well, so citizen science won out as well.

Text and photographs by Jim Fitzharris

BUTTERFLY SEASON REPORT 2021

The past two years have been very difficult for people. The limits on freedom, the endless health statistics and warnings have created an atmosphere of fear and trepidation. One anti-dote to the gloom is nature, and the ever-changing scene it delivers. No two butterfly years are alike, as Matthew Oates testifies in his splendid memoir In Pursuit of Butterflies. Oates takes his reader through his career from the early 1970s to 2013 and identifies four great butterfly years: 1976, 1989, 2006 and 2013. If his book extended to 2021, 2018 may have made the grade too. Alas, 2021 would not, but it certainly had its moments.

January was cold and wet in with above average rainfall in most places and below average temperatures throughout the country. Myrtle Parker reported the first free-flying butterfly of the year from near Minane Bridge, County Cork on January 16th but the next sighting of a butterfly had to wait until February 22nd when Michael Gray (at Ballinteer) and Niamh Lennon (at Booterstown Marsh) spotted a Small Tortoiseshell butterfly. The second half of February was much milder than the first half, and the final days saw a slew of sightings which included a Brimstone at Lullybeg, County Kildare (Pat Wyse and Jesmond Harding), and a Comma in a wildlife-friendly garden at Glenageary, County Dublin (Gillian Mollard), both on February 28th.

Amazingly, Frank Smyth saw a Red Admiral laying eggs at Howth on March 7th. This may be the earliest record of butterfly breeding ever reported in Ireland. Frank believes the female he saw laying her eggs to be a migrant, given he found no other adult Red Admirals in the area. Frank reported egg-laying by a Red Admiral a little later in the month, on March 16th. This lovely butterfly is telling us that our world is changing. More of this later. March was generally mild and dry with the month’s highest temperature, 17.6 °C, recorded on Tuesday 30th in Roscommon. Unsurprisingly, there were several records reported for that date, including the first Holly Blues (Anthony Mooney, near Maynooth, County Kildare and Peter Doyle, at Woodenbridge, County Wicklow), and the season’s first Green-veined White reported by John Lovatt from Portrane Burrow, County Dublin. The last day of March saw the first reported Small White (by Frank Smyth on Baldoyle Racecourse, County Dublin) and first Speckled Wood (two seen by Myrtle Parker at Minane Bridge, County Cork).

April was a very dry month, and sunny but cool. However, April 1st was a warm day, with the highest air temperature for the month recorded as 21.2°C, at Valentia Observatory, County Kerry. This day saw the season’s first Painted Lady, again seen by Myrtle Parker at Fountainstown, County Cork. However, we were to see very few Painted Ladies in 2021. The first days of April saw Small Tortoiseshells and Peacocks out in force and joined by the first Orange-tip of the year on April 3rd, a female reported by Con O’ Donnell from Eleven Ballyboes, Greencastle, County Donegal. Lisa Joy sent us word of the first Green Hairstreak on the 8th of April, seen at Comeen, Glenlough West, West Cork. On April 22nd Jesmond Harding reported the first Large White at Saggart, County Dublin. Throughout April, the spring butterflies were reported regularly, with no large gaps between dates, a sign of prolonged suitable weather. It was not until late in April that butterflies were reported in significant numbers, however. Some examples are the report by Con O’ Donnell on April 25th of over 20 Green-veined Whites, 15 Orange-tips and 7 Peacocks at Greencastle, County Donegal. Frank Smyth reported 8 Wall Browns at Howth on April 26th. The season was building nicely.

Then May arrived. It was cool and wet everywhere, with the east and south bearing the brunt of the rain. Sunshine levels were above average everywhere, but the rain did its damage. The Orange-tip seemed badly hit, and Cryptic Wood White was present in low numbers. The Dingy Skipper did not make its first appearance until May 7th when it was seen along with the season’s first Small Copper in Lullymore/Lullybeg, County Kildare, by Jesmond Harding. The first sighting date for the Dingy Skipper in 2020 was April 25th, nearly two weeks earlier. Even later was the first Cryptic Wood White reported on May 16th by John Lovatt from Ballyjamesduff, County Cavan; the first sighting in 2020 was on April 25th. Two early Small Heath records, one on May 8th, the next on May 13th both from Frank Smyth at Sutton and Bull Island, County Dublin, are unusually early. The next records for the Small Heath did not appear until near the end of May when Sean Feehan and Mary Jennings saw 12 on Bull Island. The first Marsh Fritillary was on the wing on May 13th , joined by the first Common Blues (notified from Bull Island by Frank Smyth). However, the early Marsh Fritillaries were outliers with substantial numbers appearing from May 26th.

Jim Fitzharris reported the first Pearl-bordered Fritillaries and Wood Whites of 2021 from Clooncoose, County Clare, on May 19th. These are under-reported because there are few observers in the Burren in May, but it is likely that the two species started their flight period later than usual owing to the cool April and cold, wet May. Also, on May 19th the first flight of the Small Blue was seen, by Frank Smyth at Sutton, County Dublin. On May 28th the first recorders to report more than 10 species sent notice of Dingy Skipper, Wood White, Large White, Small White, Green-veined White, Small Copper, Common Blue, Pearl-bordered Fritillary, Speckled Wood, Wall Brown and Small Heath, from the wonderful Clooncoose Valley in County Clare. The reporting of multiple species is a sign the season is well under way. On May 29th, the BCI outing counted over 100 individual butterflies at Lullybeg!

June brought much improved weather. It was dry everywhere, sunny and warm in the south and east with below average rainfall everywhere. The temperature was above average in most places. The highest air temperature was 25.6°C at the Phoenix Park, County Dublin, recorded on Sunday 13th. Butterfly numbers were considerably higher during early June, as many of the spring butterflies peaked. After the first week numbers fell, which is typical for most of June, when a clear gap opens between the end of the flight period of spring species and the flight period of the summer species becoming well established. This is an annual interregnum, and the vacuum includes species that have more than one generation, such as the Holly Blue and Speckled Wood. It often results in much of June feeling rather flat and confusing, with often few butterflies flying in good habitats despite good weather.

The first Meadow Brown and Ringlet of the year were recorded by Jesmond Harding at Mulhussey, Meath and Dunboyne, Meath on June 13th and 18th respectively. John Lovatt also recorded the Meadow Brown on June 13th, in Newbridge Park, County Dublin. One June 21st Sean Geraty saw the earliest Dark Green Fritillary on the magnificent Ballyteigue dunes in south Wexford. This species can be seen as early as the start of June after a warm May; in 2020 it first appeared on June 3rd. The Small Skipper was spotted for the first time in 2021 by Pat Wyse at Timahoe, County Kildare on June 28th, a not untypical start date for this species to take to the air. The 30th of June saw the first Silver-washed Fritillary, sighted at the Furry Glen in the Phoenix Park, Dublin, by Sean Geraty. This is a little early, but the site in question is dry, warm and sheltered, favouring early emergence.

July opened with grey skies and murky, sullen conditions, dissembling the glory to come. On July 15th Con O’Donnell reported the first Graylings at the rocky coast at Greencastle, County Donegal. The 15th is the date the heat wave began. That date the temperature at Greencastle was 25°C. This was just the beginning. July had prolonged hot, dry weather in the second half of the month, with the west faring best, with very little rain compared with the east. The high maximum was reported on Wed 21st with a temperature of 30.8 °C, at Mount Dillon in County Roscommon. I was in the west during this time, and the heat was extraordinary. Extreme heat is beneficial for adult butterflies, and the numbers seen showed this.

446 butterflies were counted by Con O’Donnell on Doagh Isle, County Donegal on July 16th. Nearly 200 butterflies were recorded by Stephen Bolger at the Raven the next day, 218 counted at Gortnandarragh, County Galway by Denise and Jesmond Harding on July 21st, 242 by Maurice Simms at Sheskinmore, County Donegal on July 23rd. The way to observe butterflies during very hot weather is to look for them early and late in the day. Between around midday and 5pm many butterflies will seek shade.

The first record for the Purple Hairstreak was provided by Sean Geraty on the 8th of July from the Phoenix Park. The last record for the Purple Hairstreak was from Glendalough, County Wicklow on August 25th brought to us by Jim Fitzharris. Jim also recorded the first Essex Skippers at Tacumshin Lake, County Wexford on July 16th and the first Hedge Brown/Gatekeeper at the Raven on the same date. Second generation Wall Brown were first noted by James O’Donnell on Arranmore Island, County Donegal on July 22nd; overall we received 43 reports of this endangered butterfly in 2021, compared with just 30 reports in 2020.

August was cooler than July, with low pressure over the country for most of the month bringing bands of rain between drier periods. The month’s highest temperature was reported at Athenry, Co Galway on Thursday 26th with a temperature of 26.3 °C. The final week was sunny and warmer. Late July and August are when Peacock numbers reach a peak but in 2021 we received only 185 reports of the butterfly compared with 289 in 2020. In addition, there were only three reports of numbers of 50 or more; the highest was 60 plus from Bunbeg, County Donegal in late August. This lower abundance was shared with 2020, while in 2019 much higher figures were recorded. For example, 167 Peacocks were counted at Lullymore/Lullybeg on August 8th 2019 and 150 in the same area on August 24th 2019, by Jesmond Harding. On 29th of August 2019 Frank Smyth saw 76 at Knather Wood, County Donegal. Perhaps parasites reduced their abundance over the past two years. The latest butterfly to emerge each year is the Brown Hairstreak, and the only record we received came on 15th of August from Tulla, County Clare courtesy of Jim Fitzharris.

September 2021 was very warm, one of warmest recorded. The highest maximum temperature of 27.9 °C was reported at both Shannon Airport, County Clare (its highest maximum temperature for September on record (length 75 years) and Valentia Observatory, County Kerry (its highest maximum temperature for September since 1991), both on Tuesday 7th. There was no air frost reported in September. The one limiting factor was that sunshine levels were lower than usual. September is the big decline month for adult butterflies, when the number of butterflies and range of species declines sharply. This is reflected in the records; we received 40 reports of butterflies during September 2021, while August 2021 saw 83 reports. September opened with 16 species on the wing and closed with 10 species and much lower numbers. A lovely and pleasingly more frequent feature of our Septembers is the Comma butterfly, which was just confirmed breeding here in 2014. We received nine reports in September and around 50 overall in 2021.

October was mild, wet with above average temperature throughout Ireland. It opened with a high number of species: Large, Small and Green-veined Whites, Clouded Yellow, Small Copper, Holly Blue, Red Admiral, which showed in good numbers, Painted Lady, Small Tortoiseshell, Peacock, Comma and Speckled Wood all represented. Naturally by the end of October, most records were of Red Admirals; this is typical, as many of these are feeding on ivy prior to migration. We had three species in November/December: Red Admiral, Small Tortoiseshell and Peacock.

The final record of 2021 was a Peacock seen on December 29th by Joanna O’Kane in Lifford in County Donegal. The year 2021 began and ended with the Peacock. Both were roused from their winter sleep by warm sunshine.

May the sun shine on us all in 2022.

Source: Butterfly Conservation Ireland Records Page 2021

EVENTS REPORTS 2021

Outing to Lullybeg Reserve May 29th 2021

Free at last! But freedom must be managed with the caution and restraint that characterized our outing but it was so refreshing to be in nature, in great company.

The morning began overcast but mild and the forecast promised sunshine. It kept its word.

Blackcaps and Song Thrushes were sweetly and prominently vocalizing the day’s rapture, and soon the first butterfly, a lovely male Marsh Fritillary, as fresh as the morning, flitted into our ken. Netted then released, he calmed obligingly, wings outstretched, with photo ops for all. What we did not know yet was he was the first of around 100 Marsh Fritillaries (all but one were males) we would see on our ramble, for the sun shone liberally for much of the duration.

Shortly after seeing our first Marsh Fritillary, an erratic flyer in an area of poor fen and wet heath stopped us. A Green Hairstreak, the first I have seen off a bog in Lullymore. Looking around, the presence of Cross-leaved Heath, a breeding plant, provides a potential context.

Next, we entered the “corridor” linking Lullymore and Lullybeg, expertly managed by Pat Wyse over the winter months to bring in light and regenerating heath to an area under encroachment. Here the amazing Narrow-bordered Bee Hawkmoth reigns-all the ones we sighted as pristine as the Marsh Fritillaries. Some amazing close photos were taken-see below. Again, they posed nicely for us; it was warm enough for activity but cool enough to discourage freneticism.

Marsh Fritillaries love this corridor too, having moved in to breed following scrub clearances. As a result, we now have an almost contiguous breeding habitat extending from the Irish Peatland Conservation Council Reserve in Lullymore to BCI’s reserve in Lullybeg. Brimstone egg-laying, with the female contorting her powdery abdomen in what looks like a painful procedure to deposit her precious egg, was observed close-up. Pat’s clearance means more Alder Buckthorns are now available for egg-laying Brimstones, so they can distribute their eggs over more plants, which may relieve predation pressure on the butterfly.

We passed through the corridor into the BCI reserve, looking fairly flowerless and bleached, but soon the colour of multiple Marsh Fritillaries brightened proceedings. I have not seen so many on the reserve on one day for at least a decade. This made for a momentous visit.

Another butterfly that seems to be thriving on the reserve is the Dingy Skipper-we saw at least 20, most of them in good condition. A large female Red Admiral fussed around some Meadowsweet plants, evidently mistaking the dark, wrinkled leaves for Stinging Nettles. Flashes of red revealed Small Coppers, with one tattered female laying on a tiny Sheep’s Sorrel on bare peat.

Cryptic Wood White, never numerous on the reserve, numbered five during our sojourn-a very respectably tally on this site. The southern side of the reserve was our last stop, and there were Marsh Fritillaries throughout-this is a new development-it was hitherto very scarce here. It is days like this that show that our hard work in managing the reserve is working-our resources are yielding tangible conservation results. This is thanks to all our supporters for all your help, both financial and practical.

We spent over three hours enjoying nature on this gentle, lovely day, enjoying everything from the tiny Small Purple-barred moth flitting jaggedly over the Common Milkwort to the mighty Buzzard soaring proprietorially above us.

I, for one, was delighted to be out. Thanks to everyone who took part in our walk, making the day so enjoyable.

Event Report: Moth Morning and Walk from Lullymore to Lullybeg, June 26th 2021

Cool nights rarely produce high moth counts because moths, like their diurnal relatives, need heat for activity to take place. The temperatures during the night of June 25th and 26th ranged from lows of six to 10 Celsius, not really optimal for moths. However, winds were very light, and trapping in woodland meant good shelter prevailed, encouraging activity. Prime habitat helps too. The trapping habitat holds a range of trees and shrubs, wild grasses, flowers, and habitats including the adjoining cutaway bog, bog woodland containing bramble and Bilberry, and amenity parkland with shrubs.

We improved our chances by setting several light traps in locations with different conditions to draw in as many species as possible. We were not denied.

While no trap held very high numbers, the area’s species were well represented across the traps with at least 75 species recorded. A few expected species, such as Large Emerald, Green Silver-lines, and Cinnabar, were marked absent. But some lovely moths, such as Elephant Hawkmoth, Poplar Hawkmoth, Buff and White Ermine, Light Emerald, and True Lover’s Knot were found, as well as the rare Waved Carpet. The intriguingly sculpted Scalloped Hook-tip appeared along with the Lesser Swallow and Pale Prominent moths. Great enthusiasm characterised the trap openings, with many lovely photos taken.

Moths are a world apart for humans, very much creatures of the night, of mystery and enigma. Seeing even the small fraction of the 1500 or so species we have generates much wonder, and we have much to admire and much to delight us.

We repaired to the café in the wonderful Lullymore Heritage and Discovery Park which hosted our moth event before setting off for nearby Lullybeg for our butterfly walk.

This was very well-attended, as we were joined by more BCI members and others eager to see what the wonderful Ballydermot Bog Group area has on show,

But it remained cloudy, and few butterflies were spotted. This means one must search more sensitively, more diligently, applying knowledge of the area garnered over years of experience of the good spots. Vegetation must be scrutinised, and additional eyes really help with this.

Happily, we saw several species-Common Blue, Meadow Browns, Ringlets, Small Heaths, Clouded Border moths, Silver Hook moths, a Cinnabar, Narrow-bordered Bee Hawkmoth, looking very fresh for late June, the ubiquitous Burnet Companion, as well as the larvae of the Dark Tussock, Oak Eggar, Ruby Tiger, Emperor moth, and Brimstone. We saw several dragonfly/damselfly species too including Common Hawker, Four-spotted Chaser, Blue-tailed Damselfly, and others.

Taking one’s time really enhances the experience of nature as does sharing sightings with people who love nature. The warmth and interest shown by all, and our collective learning, is the day we had.

Workday Report October 30th 2021

The days immediately before October 30th saw heavy rain but the appointed day was bright, sunny, dry, and even warm.

Our enthusiasm brightened by the conditions, we tacked willow re-growth and birch saplings on the southern side of BCI’s reserve at Lullybeg. This herb-rich area contains Common Dog-violet, Common Milkwort, Common Valerian, Devil’s-bit Scabious, Cuckoo-flower, Common Bird’s-foot-trefoil, Tormentil, vetches, and a range of grasses, all important features for moths and butterflies.

This area is used for breeding by two rare moths, Narrow-bordered Five-spot Burnet and Small Purple-barred, and a threatened butterfly, the Dark Green Fritillary. The main challenges to the habitat on Lullybeg Reserve are the growth of willow and birch which, if left untackled, will change the habitat from species-rich wet grassland to scrub and eventually woodland. While these habitats are important for other species, these habitats are very well represented on the site and in the general area.

Thanks to the wet peat soils and their shallow roots, the birch saplings were easy to uproot. The willow needed to be cut back and uprooted applying more force and all the plants were placed in piles and later moved into an area of dense scrub to leave the grassland clear.

We took a break for lunch and basked in the late autumn sun, which beamed warmly on us and our conversations. We managed to see a few late insects, including a late Small Tortoiseshell, a few micro-moths, including Acleris notana, a species that breeds on birch and hibernates as an adult moth. Three dragonflies, Black and Common Darter and Migrant Hawker were spotted, their gauzy wings gleaming in the sharp, shallow autumn light.

By the time we finished our work, a large amount of open grassland was achieved. We found some Common Dog-violet plants with mature leaves showing feeding damage, probably from Dark Green Fritillary caterpillars earlier in the year. Thanks to our work, the plants remain unshaded and available for the next generation which we hope to see flying next June.

A very special thanks to all who worked so hard to keep the habitat in the best condition for our reserve’s butterflies.

CRABTREE RESERVE REPORT 2021

| Species Recorded | Site Total 2020 | Site Total 2021 | Site Total 2021 less Site Total 2020 | Transect

Total 2020 |

Transect Total 2021 | Transect Total 2021 less Transect Total 2020 |

| Dingy Skipper | 10 | 47 | 37 | 9 | 8 | -1 |

| Brimstone | 52 | 47 | -5 | 25 | 26 | 1 |

| Cryptic Wood White | 6 | 6 | No change | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| Green-veined White | 7 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 10 | 5 |

| Orange-tip | 2 | 1 | -1 | 2 | 1 | -1 |

| Large White | 2 | 2 | No change | 1 | 0 | -1 |

| Small White | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Green Hairstreak | 1 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | No change |

| Common Blue | 36 | 31 | -5 | 36 | 21 | -15 |

| Holly Blue | 1 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | No change |

| Small Copper | 20 | 13 | -7 | 9 | 4 | -5 |

| Red Admiral | 13 | 2 | -11 | 4 | 1 | -3 |

| Painted Lady | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Small Tortoiseshell | 231 | 270 | 39 | 150 | 198 | 48 |

| Peacock | 48 | 39 | -9 | 21 | 30 | 9 |

| Comma | 0 | 0 | No change | 0 | 0 | No change |

| Dark Green Fritillary | 21 | 11 | -10 | 14 | 8 | -6 |

| Silver-washed Fritillary | 9 | 6 | -3 | 4 | 3 | -1 |

| Marsh Fritillary | 163 | 287 | 124 | 97 | 182 | 85 |

| Wall | 1 | 1 | No change | 0 | 0 | No change |

| Speckled Wood | 11 | 7 | -4 | 5 | 4 | -1 |

| Meadow Brown | 204 | 417 | 213 | 132 | 295 | 163 |

| Ringlet | 588 | 1097 | 509 | 424 | 775 | 351 |

| Small Heath | 44 | 74 | 30 | 37 | 58 | 21 |

| Large Heath | 0 | 0 | No change | 0 | 0 | No change |

| Total | 1472 | 2373 | 901 | 979 | 1633 | 654 |

The butterflies on Butterfly Conservation Ireland’s Crabtree Reserve at Lullybeg are counted by walking the transect route (a fixed route walk through a range of habitats that reflect those found on the reserve) on part of the reserve from April to the end of September and in October if conditions favour butterfly activity. Results are sent to the National Biodiversity Data Centre for the Irish Butterfly Monitoring Scheme. Butterflies seen outside the transect route are counted separately. Both counts are reflected in the table above. In 2020, 24 transect counts were made; in 2021, 21 counts were made. The figures for 2020 are compared against the 2021 figures.

Abundance variations between years even within sites are normal. A cumulative ongoing decline in abundance is a cause of concern especially for species that are ranked as threatened or near threatened on the butterfly red list. The table shows that 11 out of 25 species showed declines on the 2020 figures and another three species were not seen on the reserve in 2021. None of the declines are large and mostly represent ecological conditions unrelated to reserve quality. The one decline that is worrying is the drop in the Dark Green Fritillary, which has fallen over the past three years, despite the presence of suitable breeding conditions in various parts of the reserve. We will be attempting to address this decline by removal of birch saplings on the southern side of the reserve to add more breeding habitat; some of this work was carried out during a management day in October 2021.

The major successes on the reserve in 2021 are two priority species, the Small Heath and the Marsh Fritillary. The Small Heath has shown worrying declines on the reserve, and we are very concerned about this situation. In last year’s report we mentioned that the reliance of the Small Heath on finer grasses for breeding makes it vulnerable to the development of ranker grasses on the reserve. This latter issue might be addressed by soil disturbance to interrupt successional change and summer grazing and to create warmer conditions at ground level where vegetation abuts on bare soil. We have noticed that dense tufts of Red Fescue, growing at a high density in open, unshaded situations are where the highest numbers of the Small Heath are concentrated.

We will avoid disturbing the soil or grassland vegetation in these areas, but we will ensure these remain unshaded. The good news is that 2021 saw the butterfly increase by 30 individuals in 2021, up from 44 in 2020 to 74 in 2021.

The Marsh Fritillary hit a record high of 287 individual butterflies in 2021, and we suspect we undercounted the species. The population has been increasing since 2016, and we are delighted that our management of the reserve has paid off for this endangered butterfly.

The other species to show a large increase is the Ringlet, nearly doubling its numbers in 2021 to 1097 individual Ringlets. This grass feeder may have benefited from the wet May weather, which may have boosted grass growth. In 2020 numbers were well down, probably because very heavy rain in February may have drowned some larvae, which at that time of the year lie tucked away at the base of grass tufts. Following that flooding, the spring of 2020 had a drought, which may have affected foodplant quality. Whatever the reason for the recovery, we are delighted to see it bounce back.

Two species that usually show in high numbers on the reserve and throughout the wider area, the Brimstone and Peacock, remained in low numbers again in 2021. There seems to be no reason related to habitat quality or foodplant availability to explain these sharp falls, so it appears that a feature such as larval losses due to direct predation by birds in the case of the Brimstone and parasites and viruses in the case of both Brimstone and the Peacock might be responsible.

Provided we maintain the habitat conditions needed, these species will be in position to benefit when predation levels fall.

We did not see the Holly Blue, Green Hairstreak, Comma or Large Heath on the reserve in 2021 although the former three were seen in the area. We expect the Holly Blue and Comma to become regular inhabitants in the years ahead, given the expansions in their distribution and the suitability of the habitat on offer on our reserve.

Thanks are due to all who helped with reserve management during 2021. Without your help, our reserve would not be the butterfly hotspot it is.

CONSERVATION NEWS

During the winter months of January and February 2021, lockdown measures meant that the planned work party could not proceed. Some scrub clearance by hand was undertaken by individual members and this made a great difference to the habitats, particularly for the Marsh Fritillary, Dingy Skipper and Brimstone. Scrub on the broad ride through woodland connecting Lullymore and Lullybeg was cut back to ensure that the two excellent areas remain linked so that butterfly populations in the area do not become isolated. Machinery from Lullymore Farm cut back an extensive area of scrub along the access route to the site and along the silt pond on the northern edge of the reserve which allowed flora to bloom which was used as a feeding area by butterflies, especially Peacock and Painted Lady. On September 7th, 2021, 65 Marsh Fritillary larval nests were found on the reserve up from 29 nests found in September 2020. These nest counts represent a booming population. Our recording scheme begun in 2013 continued in 2021. The recording season was less impacted by government restrictions in 2021 which eased during spring.

Our online platforms were used to promote conservation throughout 2020. Various blogs were written to draw attention to butterfly and moth species that may be seen at the various times of the year, to conservation measures one can take to enhance gardens and public spaces for butterflies, to promote recording, to comment on findings of various reports on butterfly and moth populations and to report on Butterfly Conservation Ireland outings. Our Facebook page presents very attractive images sent in by members and by the public, as well as publicising our work/events. Conservation and habitat enhancement advice was provided to a range of bodies and members of the public

Following the announcement by Bord na Móna of government and EU-funded peatland rehabilitation schemes which involve re-wetting cutaway and cutover bogs, Bord na Móna has produced Cutaway Bog Decommissioning and Rehabilitation Plans for several bogs. Butterfly Conservation Ireland made submissions to Bord na Móna regarding the plans for these bogs. Butterfly Conservation Ireland is alarmed that these plans do not make any commitment that the rehabilitation works for the selected bogs will permanently secure these bogs for biodiversity and climate action. We have argued that no future use that compromises the rehabilitation of any rehabilitated peatland be considered.

Despite the cessation of peat cutting on Bord na Móna bogs, illegal cutting on some bogs has been taking place. We have reported this to Bord Na Móna’s land management team, with photographs of equipment used to cut the bogs. It is Bord na Móna’s responsibility to secure their landholding and report illegal, unlicenced activity to the Gardaí.

Serious challenges remain because many legally protected bogs that are not state-owned are being destroyed and little or even nothing is being done to uphold the law. We will continue to lobby the government to stop this illegal activity. This is a scandalous breach of the law, and no one should expect to escape punishment for this criminal activity. Mouds Bog, County Kildare is an example of a protected bog that is being damaged in plain sight of the state and no prosecution has been taken to punish criminal wrongdoing. While this lack of commitment on the state’s part exists, our bogland butterflies and moths and their habitats stand little chance.

During 2021 conservation we raised concerns on behalf of two sites, Gortnandarragh Limestone Pavement Special Area of Conservation in County Galway and Harristown Common in County Kildare. Both sites sustained damage to their habitats. Issues arising were reported to the National Parks and Wildlife Service. The issue-raising is important because it encourages the Wildlife Service to conduct site visits to ensure that the conservation values of the site, typically reflected in the conservation status of the features that qualify the sites for designation are not being adversely affected by prohibited activities.

A major project that Butterfly Conservation Ireland became involved in during 2021 is the campaign to obtain a new national park for Ireland. This campaign involves seven local and national environmental organisations. In June the campaign group on which Butterfly Conservation Ireland has a seat presented a proposal for a major new 7,000-hectare National Peatlands Park in Kildare and Offaly, at a meeting with Bord na Móna. The Group have already presented its proposal to Government and to the Strategic Policy Committees in Kildare County Council. The proposals have received endorsement by the Committees and have been identified for attention in the proposed new County Development Plan for Kildare.

The habitats involved contain some of the best habitats in Ireland for butterflies, moths, a range of other invertebrate groups, mammals, birds and plants. The proposal would deliver protection for a vast area of bogland, woodland, river and other wetlands and create a major opportunity for the social and economic development of a less advantaged area in Ireland’s midlands. Five of our six national parks lie on the western seaboard with the remaining park near the east coast (Wicklow Mountains National Park). There is no national park for the midlands and none at all based on raised bog habitat.

This project is ongoing and has resulted in intensive engagement and planning. We hope to have some positive news on this venture in 2022.

BCI members have continued to work hard, organising and carrying out fundraising, recording, participating in practical conservation work and, very importantly, enjoying our butterfly and moth heritage.

Please continue your recording and conservation work in 2022; no matter how small your work may seem you can make a difference. Some man-made habitats, such as gardens, often contain a greater range of biodiversity than semi-natural habitats because of the diversity of habitats and micromanagement possible in a garden.

Finally, Butterfly Conservation Ireland thanks everyone who helped with our conservation work in 2021. Conservation is a battle for the preservation of everything that is good about our natural world and we greatly appreciate your commitment to the most elegant emblems of our natural heritage, our butterflies and moths.

GARDEN SURVEY REPORT 2021

The Comma is becoming a more frequent visitor to gardens in parts of eastern Ireland, a scenario unthinkable just 20 years ago. Photo J. Harding.

The Comma is becoming a more frequent visitor to gardens in parts of eastern Ireland, a scenario unthinkable just 20 years ago. Photo J. Harding.

Butterfly Conservation Ireland members and members of the public participated in our garden survey from March to November inclusive. The survey form, available as a download from our website www.butterflyconservation.ie and available by post on request asks the participant to record the first date each butterfly listed on the form was first recorded in their garden in each of the following three-month periods: March-May, June-August and September-November. In a final column, the highest number of each butterfly seen and the peak date is given. Finally, surveyors are asked to indicate which of the following attractants are provided in their gardens: Buddleia, butterfly nectar plants other than Buddleia and larval food plants. Twenty butterflies are listed for recording. The following report comments on the 2021 flight season, outlines the status of these butterflies in gardens during 2021, offers interpretations and comments on the findings and concludes by urging conservation and involvement in recording garden butterflies.

With many of us somewhat restricted in our movements during parts of 2021 we had ample time to observe our local butterflies including those visiting our gardens. We saw some high abundance figures in some gardens. Robert Donnelly, with his superb garden in Ballyknock, County Kilkenny counted 137 Small Tortoiseshells on August 24th. One recorder, Michael Gray, whose flower-rich garden is in Rathfarnham, Dublin, recorded fewer butterflies (115) in 2021 than in the previous four years 2017-2020. The peak year in Michael’s garden was 2017 when 166 butterflies were recorded. One observer, Elaine Mullins from Portmarnock, counted every individual butterfly she saw during the recording period. Elaine’s beautiful suburban garden returned 69 individual Holly Blues between March 31st and August 28th and and 71 reports of the Large White between April 21st and September 24th. Marilyn Farrell, whose wonderful County Kerry garden featured in The Irish Times on August 29th 2020 (https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/homes-and-property/gardens/you-could-stick-a-broom-handle-in-the-kerry-ground-and-it-would-grow-1.4335891) yielded 524 individual butterflies.

August 24th, 2021, was a key date for many observers with some season peaks recorded on that date. The day was warm and sunny, with a peak temperature of 24 Celsius. Early September, especially between September 1st and 5th were also important for many recorders, especially with continued warm weather, with the temperature in the low 20s Celsius. As was the case in 2019 and 2020 the last week in August and the first week in September saw high butterfly counts but this pattern was not repeated across the country. For example, Marilyn Farrell, in Ireland’s southwest, saw her peak butterfly numbers in mid-September, especially on September 15th.

The total number of species recorded in the gardens surveyed was 17, the same as in 2020 but down from 18 in 2019 and 2018. The missing butterfly is the Clouded Yellow. The total of 17 garden butterfly species is up from 15 in 2017, up on 14 in 2015 and 2016, and level with 2014. Interestingly, only the Small Tortoiseshell and Peacock were recorded in all gardens 2020 but in 2021, the following appeared in all the gardens surveyed: Large White, Small White, Red Admiral, Small Tortoiseshell, Peacock and Speckled Wood. The Green-veined White and Meadow Brown were recorded in all but one garden in 2021. It appears that our recorders are improving their garden habitats or recording skills or both! The Holly Blue, a species that likes to breed in gardens was reported by all but one surveyor in 2020 but was marked absent in a few gardens in 2021, including mine! The Holly Blue loves to breed in warm, sunny gardens with warm, bare walls and shelter, and is especially happy in Dublin city centre and in gardens near the Dublin coast.

Female Holly Blue, spring generation. This one laid an egg on the buds on the plant she has settled on, a dogwood (Cornus spp) in a garden in Clontarf, County Dublin. Photo J. Harding.

The Large White had another very good year and bred in some gardens, especially on nasturtiums. Pat Bell, whose garden is in Maynooth, County Kildare had a peak of eight on August 22nd, Jesmond Harding, some miles to the north in Mulhussey, County Meath had 10 on August 13th while Robert Donnelly counted 22 on May 29th. Elaine Mullins, Portmarnock counted 151 individual Large Whites over the survey period. The Large White butterfly probably produced a third generation with some recorders reporting adults at the end of September and into October. Interestingly, in Elaine Mullin’s garden, there is evidence of a clear gap between the end of the first generation at the end of May (it began flying in Elaine’s garden on April 21st) and the start of the second generation from July 12th. From July 12th, it remained in flight until September 24th, without a defining gap. Typically, when assessing the number of generations that a butterfly produces, a gap between each generation’s flight period is identified. However, no gap appears in Elaine’s records after July 12th, suggesting that the Large White produced an extended second generation or two overlapping broods, with the second generation overlapping with the third. Given the late dates of a small number of individuals, it is likely that a third generation flew in the Dublin area during 2021, and in Donegal, but it is very difficult to be certain. The situation becomes more complex when one considers the possibility that some of the Large Whites may have been inward migrants.

Interestingly, there was a boom in the Small White population in my area of south Meath in early August, but this was not clearly reflected in the findings overall, so this abundance may have been localised to a small area.

The Comma was reported from gardens in Kilkenny (the highest number on one day is nine, an unusually high number, especially for a garden), Kildare and Dublin. I was thrilled to see at least two in my Meath garden, in late August and late September. The Silver-washed Fritillary, not really considered a garden butterfly, presented its stately credentials in two gardens, Robert Donnelly’s and Pat Bell’s. The Painted Lady, ubiquitous in 2019, appeared in smaller numbers in fewer gardens. However, Robert and Jane still got 9 on August 13th in Kilkenny. A boom-and-bust pattern in this migrants’ appearance in Ireland is the norm!

Other less common garden visitors in 2020 were the Orange-tip, Cryptic Wood White, Small Copper and Common Blue (a low-flying grassland breeder which contrasts with the high-flying hedgerow-inhabiting Holly Blue).

The Orange-tip visited many gardens in 2021, but in low numbers in most. Photo J. Harding.

The Orange-tip visited many gardens in 2021, but in low numbers in most. Photo J. Harding.

Regarding the brown family, the Meadow Brown was found in most gardens but numbers varied; the Speckled Wood, recorded in all gardens is territorial in the male so numbers in most gardens will be low; the Meadow Brown and Ringlet are more social and much more tolerant of their own kind, allowing numbers to build if the habitat is sizable and suitable. Because the Meadow Brown is less specialised, occurring in open and partly shaded areas, in long and short swards, it is often more numerous in gardens; Jesmond Harding had a peak count of 10 Meadow Browns but just single Ringlets. With the right mix of grassy habitats and space for these, more can be achieved. Peak counts of 26 Ringlets and 23 Meadow Browns were made by Robert Donnelly.

The earliest garden butterfly recorded in gardens in 2021 was Small Tortoiseshell seen on February 28th. The last butterfly reported from a garden in 2021 was a Small Tortoiseshell seen on October 9th. Some recorders sent notes of other notable species; Pat Bell, Maynooth, was very lucky to record a Currant Clearwing, a rare day-flying moth. Pat also had the Cinnabar moth and Migrant Hawker in his garden. Habitat mosaics, where a range of habitats are built together as is the case in Pat’s garden pays off when you want to cater for as many species as possible.

Current Clearwing moth. Photo Pat Bell.

Current Clearwing moth. Photo Pat Bell.

Butterfly Garden Tips

And with the ravaging of our natural and semi-natural habitats, that approach to gardening for nature is increasingly important. A pond and associated wetland will be used by a range of animal groups including dragonflies, amphibians, hoverflies as well as butterflies and moths. With the climate models showing longer periods of dry weather in spring and summer, species that breed in damp grassland may become highly dependent on permanently wet areas for survival. The Green-veined White and Orange-tip will become increasingly needful of marshy ground. In short, they will need our help. The great pioneer of wildlife gardening, Professor Chris Baines, commented that a garden without a pond is like a theatre without a stage. An unshaded pond and wetland, stocked with native plants will generate great activity in your garden. Make this your conservation project in 2022.

Other important points concern the overall management of your garden habitats. If growing a semi-natural, flower-rich grassland, opt for a cutting regime that allows your flora to bloom and set seed. If it is a spring flowering meadow, leave it uncut until late in June. If your meadow plants are mainly summer flowering, leave it uncut until later in September, depending on seasonal conditions. Thus, in some years the flowering and seed-setting occurs earlier and the meadow can be cut accordingly. Avoid cutting on a low setting unless you want bare patches. There may be a very good reason for wanting bare soil, which adds warmth to a meadow providing basking sites and enhancing breeding conditions where bare soil abuts caterpillar foodplants.

Please do not use chemicals in your garden. Many gardeners, no doubt influenced by the horticultural industry are obsessed with spraying shrubs to kill aphids. Aphids have a range of natural controls in a healthy garden to keep their numbers in check. Aphids also produce ‘honeydew’, a sugary substance excreted on the surface of leaves. This is food for several shrub and tree-loving butterflies, including Holly Blue, Brown and Purple Hairstreaks, Speckled Wood and most likely the Red Admiral too. Allow nature to exert its own influence on events. In a balanced habitat, rarely does any species dominate.

Avoid fertiliser use. Fertiliser often boosts plant growth but suits the aggressive species most, crowding out more delicate plants that prefer to have less nitrogen. There is recent research to show that grassland fertiliser poisons butterfly and moth larvae. It also causes excessive greening of grassland vegetation, cooling temperature close to the ground which makes conditions unsuitable for growth for caterpillars that need warmth to develop.

For the same reasons, remove the cut vegetation from your meadow. Place it in a compost heap to use on your vegetable patch, or even in a place in your garden where the ground slopes downwards, such as near a hedge, where the extra fertility will encourage Stinging Nettles, a vital plant for many of our moths and butterflies.

Get Involved

We hope to expand the garden recording scheme further in 2022. Our website www.butterflyconservation.ie contains information about butterfly gardening; click on the “Butterflies” tab and select “Gardening for Butterflies” for details. The survey form can be downloaded from here but if you need a hard copy please request one by emailing us at conservation.butterfly@gmail.com or by letter to Butterfly Conservation Ireland, Pagestown, Mulhussey, Maynooth, County Kildare. If you have any doubts about the identity of any butterfly check our Gallery by clicking on the “Butterflies” tab. Thank you for taking part in the scheme and please continue your recording. Recording begins again in March and here’s hoping for a good season in 2022.

Wilder gardens with Meadow Vetchling may attract the Cryptic Wood White. Photo J. Harding

Wilder gardens with Meadow Vetchling may attract the Cryptic Wood White. Photo J. Harding

Butterfly Atlas in Kildare

While many butterfly lovers rightly flock to the Burren in County Clare to sample its amazing butterfly diversity and abundance, there is a county much closer to our greatest population centre with much to offer the nature lover in general and the butterfly enthusiast in particular. In the following article, our own Pat Bell, a native of County Kildare, highlights the recording effort that has helped to highlight Kildare’s importance for butterflies and their habitats.

Kildare must be one of the best counties in Ireland for butterfly enthusiasts! It has Ireland’s only two butterfly reserves, unique habitats such as the Curragh and Pollardstown Fen not to mention the vast Bog of Allen. You are never far away from a waterway in Kildare whether it is one of the major canals or their feeders and branches or the beautiful Liffey and Barrow rivers and not forgetting the Boyne as it flows from its source at Carbury and wraps around Rahin Wood before leaving the county. There are renowned heritage houses such as Carton, Castletown and Leixlip Castle and nationally important woodlands like Donadea Forest and Killinthomas Wood.

Surveys and Recording

Not surprisingly, with such attractions, there are many butterfly enthusiasts in the county. At the start of 2017 there were nine sites in Kildare participating in the National Biodiversity Data Centre’s (NBDC) Irish Butterfly Monitoring Scheme (IBMS) including two of the original sites at the start of the scheme in 2008, Jesmond Harding on Butterfly Conservation Ireland’s (BCI) reserve at Lullybeg and Irish Peatland Conservation Council’s (IPCC) reserve at Lullymore.

Running from 2017 to 2021 the Butterfly Atlas will bring together information from all butterfly recording activities into one over-arching project. These include the IBMS, 5-visit and single-species monitoring schemes and casual records of butterflies. The project is an all-island initiative being coordinated by the National Biodiversity Data Centre in collaboration with BCI, Butterfly Conservation UK and the Centre for Environmental Data and Recording, supported by the Dept. of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht and the Northern Ireland Environmental Agency.

A remarkable total of 11,321 casual records from Kildare were submitted online by recorders with even more yet to be added from BCI’s recording system which will consolidate the county’s position on top of this recording table. In the 5-visit scheme 36 sites were surveyed making Kildare the best-surveyed county under this scheme also – approximately 300 survey walks were undertaken contributing more than 4300 records to the Atlas, a phenomenal achievement! A big job lies ahead for the National Biodiversity Data Centre of validating records, undertaking a complicated statistical analysis bringing all three elements together leading to publication of the Atlas, targeted for 2023.

The first 5-visit survey was undertaken in 2017 on the beautiful Barrow Way south of Athy by this writer who in early 2018 got together with Paddy Sheridan of Wild Kildare and Eddie Gilligan to plan their approach to the 5-visit surveys in 2018 and coordinate with other enthusiasts in the county. The target at this point was to ‘green’ the 10km square survey map of Kildare produced by the National Biodiversity Data Centre with an emphasis on the identified priority squares.

This effort was successful and by the end of 2018 approximately 60% of the 10km squares had been surveyed. Paddy also did a huge amount of casual recording in 2018 to such an extent that an outline of Kildare could be seen on the map of Ireland’s casual records at the end of the year – Paddy had been in literally every corner of the county! He had by now also caught the 5-visit surveying bug and he undertook no less than 11 new transects in 2019. Getting all this effort online was quite the job and with the 10km square map now well filled in we started looking at the 5km level to identify sites of interest.

2020 was our annus horribilis with the Covid-19 lockdown and then in December Paddy suddenly passed away, a terrible shock to all wildlife lovers in Kildare and beyond. As 2021 was the last year of the Atlas this writer liaised with several recorders and some missing iconic locations in the county were surveyed such as Carton House, The Curragh of Kildare, Killinthomas Wood and Pollardstown Fen – a fitting tribute to Paddy who loved his county.

Results and Outcomes

Analysis of results is beyond the scope of this article at this time as there is a huge job of validation and statistical analysis yet to be carried out by the National Biodiversity Data Centre. The following is a preliminary look at some of the available online data and information on the 5-visit scheme provided by the National Biodiversity Data Centre.

Approximately 30 of Ireland’s 35 species of butterfly may be seen in Kildare but not all at the same time or same place of course due to factors such as seasonality and habitat specialisation. The uncertainty regarding the exact number is due to unvalidated records of some marginal species. In the National Biodiversity Data Centre’s database of casual records, the 12 most recorded species for the Atlas period in Kildare are: Small Tortoiseshell (1482 records), Green-veined White (1371), Speckled Wood (1218), Peacock (986), Small White (916), Orange-tip (633), Red Admiral (633), Meadow Brown (629), Large White (555), Common Blue (497), Ringlet (496) and Painted Lady (435).

A preliminary analysis of the two survey schemes has a similar outcome but with the Ringlet and Meadow Brown ranking higher, perhaps because they are recorded more thoroughly in these schemes than by casual sightings. The migrant Painted Lady is very variable and had one of its ‘big years’ in 2019. Analysis of abundance has yet to be carried out.

Two species that have been doing well in Ireland in recent years, the Brimstone and Silver-washed Fritillary, have also been doing well in Kildare and are just outside the top 12. The distribution maps below are produced from unvalidated casual records from 2017 to 2021.

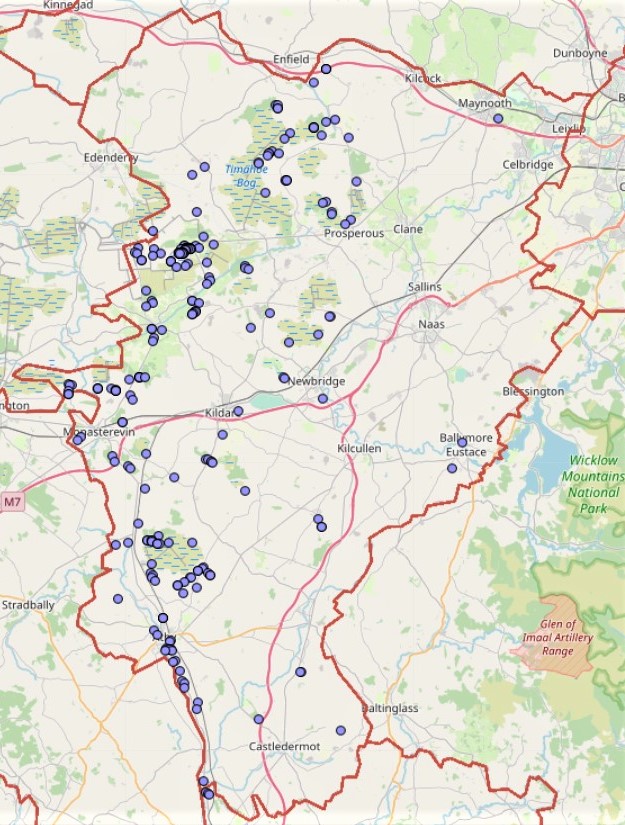

Brimstone casual records 2017-2021 NBDC

Brimstone casual records 2017-2021 NBDC

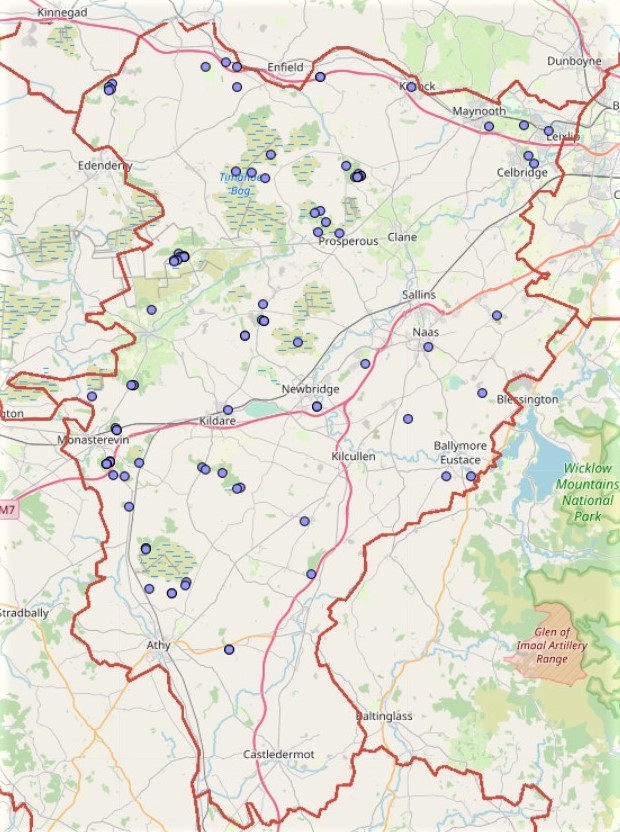

Silver-washed Fritillary casual records 2017-2021 NBDC

Silver-washed Fritillary casual records 2017-2021 NBDC

Although the Brimstone is more numerous than the Silver-washed Fritillary here, the latter performs strongly in some of the site surveys. Both butterflies are habitat specialists and while there are similarities in these two distribution maps there are also interesting differences. The Brimstone’s larvae feed exclusively on buckthorn leaves and the alder buckthorn is widely distributed in the acid conditions found in bogs. This is evident in its broad sweeping distribution down the western bogs from Timahoe through Lullymore/Lullybeg, Umeras and Kilberry and then into the Barrow Way.

The Silver-washed Fritillary on the other hand is a butterfly of woodland with an intriguing lifecycle whose larvae feed on violets. While occurring in young bog woodland it has notably been recorded in mature woodland at Rahin Wood, Moyvally, Donadea Forest, Carton House, Castletown House and Louisa Bridge. Encountering these stunning butterflies is always a joyful experience.

Sites and Habitats

The number of butterfly species on a site is a good indicator of habitat variation and richness. A preliminary analysis of the 46 surveyed sites shows up three sites with an impressive 20 or more species, Lullymore West, Lullybeg Butterfly Reserve and Hortland. It’s interesting to note that these three sites are all cutaway bog with some woodland also at least nearby – great mixed habitat in other words and the first two have important colonies of Marsh Fritillary. They are also IBMS sites with weekly counts which might give them an edge over 5-visit sites in picking up occasional species. In addition to the three species just mentioned, other less common species found here include Dark Green Fritillary, Dingy Skipper, Small Copper and Small Heath.

Brimstone at Lullymore.

Brimstone at Lullymore.

Silver-washed Fritillary at Castletown (Rory Finnegan)

Silver-washed Fritillary at Castletown (Rory Finnegan)  Louisa Bridge Special Area of Conservation at Leixlip (Eddie Gilligan).

Louisa Bridge Special Area of Conservation at Leixlip (Eddie Gilligan).

Five more sites with just under 20 species are Ardmore on the southern fringe and Cloney Beg on the northern fringe of Kilberry Bog, Ballinafagh Bog, Christianstown and Louisa Bridge . The non-bog site of Louisa Bridge in Leixlip is a Special Area of Conservation and is rich in wildflowers with a good variation in habitat also as it extends down to the Ryewater. Sites with less varied habitats are not necessarily less important and can hold important specialist colonies such as Small Heath on the Curragh and Large Heath on Ballinafagh Bog. This latter species is also the subject of a single-species collaborative project between the National Biodiversity Data Centre and the Irish Peatland Conservation Council on their Lodge Bog site at Lullymore. A similar project is also carried out by the Irish Peatland Conservation Council with Marsh Fritillary on their butterfly reserve in Lullymore West.

There are many other stories still to tell such as the mystery of Kildare’s rare skippers, the Purple Hairstreak in the castle not to mention the ongoing amazing expansion of the Comma. At the start of 2017, the Comma was primarily to be found only in the southwest of the county on the Barrow Way, as it expanded its range out of the southeast of the country, and at the end of 2021 it is being recorded in gardens in northeast Kildare and beyond – the story never stands still!

Jesmond Harding leads a group walk on Butterfly Conservation Ireland’s reserve at Lullybeg. Photo Pat Bell

Survey Sites and Recorders in Kildare for Butterfly Atlas (2017-2021)

| Survey Site | Recorder | Survey Type | Years | Grid Ref | |

| 1 | 15th Lock, Grand Canal | Pat Bell | 5V | 2021 | N916242 |

| 2 | Ardenode Stud | Theresa Bennett | IBMS | 2020-2021 | N908093 |

| 3 | Ardmore | Paddy Sheridan | 5V | 2019-2020 | S689986 |

| 4 | Ballina | Paddy Sheridan | 5V | 2020 | N720420 |

| 5 | Ballinafagh Bog | Pat Bell | 5V | 2018 | N822279 |

| 6 | Ballyteague | Paddy Sheridan | 5V | 2019-2020 | N740239 |

| 7 | Barrow Way, Ardreigh, Athy | Pat Bell | 5V | 2017-2019 | S692916 |

| 8 | Burtown House | Paddy Sheridan | 5V | 2019-2020 | S760945 |

| 9 | Calverstown Demesne (farm) | Mireille McCall | IBMS | 2017-2019 | N808034 |

| 10 | Calverstown Demesne (garden) | Mireille McCall | IBMS | 2017-2019 | N805034 |

| 11 | Carton House | Pat Bell | 5V | 2021 | N954376 |

| 12 | Castletown House Parklands | Pat Bell | 5V | 2019-2021 | N985340 |

| 13 | Christianstown | Paddy Sheridan | 5V | 2019-2020 | N747196 |

| 14 | Cloncurry Bridge, Royal Canal | Sandra Sheridan | 5V | 2018-2020 | N815424 |

| 15 | Cloney Beg | Val Swan | 5V | 2019-2021 | N683023 |

| 16 | Corballis Hill | Paddy Sheridan | 5V | 2019-2020 | S825869 |

| 17 | Corbally (Branch of Grand Canal) | Theresa Bennett | 5V | 2019 | N842147 |

| 18 | Cornamucklagh | Paddy Sheridan | 5V | 2019-2020 | N666411 |

| 19 | Cromwellstown | Paddy Sheridan | 5V | 2019-2020 | O012217 |

| 20 | Curragh of Kildare | Val Swan | 5V | 2021 | N761129 |

| 21 | Davidstown House, Castledermot | Alberto Villarejo | IBMS | 2017-2020 | S813891 |

| 22 | Derrylea | Paddy Sheridan | 5V | 2019-2020 | N596154 |

| 23 | Donadea Forest | Sandra Sheridan | 5V | 2019 | N833329 |

| 24 | Fisherstown Bridge, Barrow Line | Val Swan | 5V | 2018 | N615070 |

| 25 | Grand Canal, Lyons Demesne | Eddie Gilligan | 5V | 2018 | N964288 |

| 26 | Grand Canal, Rathangan | Vanessa Mack | 5V | 2018-2021 | N664183 |

| 27 | Hortland | Paddy Sheridan | IBMS | 2017-2020 | N795366 |

| 28 | Kill Hill | Jimmy O’Byrne | 5V | 2019-2020 | N951228 |

| 29 | Killinthomas Wood | Vanessa Mack | 5V | 2021 | N671215 |

| 30 | King’s Bog | Paddy Sheridan | 5V | 2019-2020 | N713088 |

| 31 | Leixlip Castle | Eddie Gilligan | 5V | 2019 & 2021 | O003357 |

| 32 | Leixlip (Hill) | Paddy Sheridan | 5V | 2019-2020 | O011365 |

| 33 | Leixlip Reservoir, Barnhall | Eddie Gilligan | 5V | 2021 | N994342 |

| 34 | Louisa Bridge, Leixlip | Eddie Gilligan | IBMS | 2017-2019 | N994365 |

| 35 | Lullybeg Butterfly Reserve | Jesmond Harding | IBMS | 2017-2021 | N685256 |

| 36 | Lullymore East | Pat Bell | 5V | 2021 | N718252 |

| 37 | Lullymore West | IPCC | IBMS | 2017-2021 | N693261 |

| 38 | Maganey | Paddy Sheridan | 5V | 2019-2020 | S718852 |

| 39 | Moyle Abbey | Paddy Sheridan | 5V | 2020 | S810977 |

| 40 | Philipstown | Paddy Sheridan | 5V | 2018-2020 | N974169 |

| 41 | Pollardstown Fen | Michael Jacob | 5V | 2021 | N771157 |

| 42 | Ponsonby Bridge, Grand Canal | Pat Bell | 5V | 2019 | N928256 |

| 43 | Rahin Wood (Russellswood) | Pat Bell | 5V | 2019-2020 | N627393 |

| 44 | Royal Canal, Kilcock | Pat Bell | 5V | 2021 | N885396 |

| 45 | Royal Canal, Maynooth | Pat Bell | IBMS | 2017-2021 | N940375 |

| 46 | Stacumny | Pat Bell | IBMS | 2017-2018 | N997318 |

5V = 5-visit Survey; IBMS = Irish Butterfly Monitoring Scheme

Hedgerows in our landscapes-how important are they for Butterflies and Moths?

A hedgerow is a linear feature consisting of a row of closely planted bushes or trees which, when clipped, can form a dense barrier. Typically, they are planted as boundary markers and to divide fields. They are man-made in the sense that hedgerows are planted but in the Irish, British and European countryside, hedgerows consist mainly of native plants. In Ireland, these are mainly Common Hawthorn, Common Blackthorn, Common Hazel, Common Holly with gorse and Grey Willow commoner on wetter soils. Other plants that occur in hedges are Common Yew, Common Spindle, Common (Purging) Buckthorn and occasionally Alder Buckthorn. Many hedgerows contain trees, especially Pedunculate Oak, Rowan, Common Ash and Common Beech. Hedges bordering roads are often planted on top of or into the side of a bank of soil dug to form a drain. In farmland extended field margins comprising native flora, such as herbs and grasses, often extend outwards from the hedge for a metre or more, providing adjoining grassland habitat.

This species-rich hedgerow contains around 14 tree species.

This species-rich hedgerow contains around 14 tree species.

When we walk, cycle, or drive along our rural roads, hedgerows give our countryside a far more wooded appearance that belies the true low state of woodland cover in this country. Native woods cover less than 2% of our total land area, while another 8% is under plantation forestry, mostly non-native conifers (Cross 2012) which have a much lower value for our native plants and animals.

Just how important are hedgerows in a landscape largely denuded of native trees? Personal experience suggests that hedgerows are extremely important, containing as they do native trees and shrubs and native flowers and grasses. A walk along the sunny side of a hedge in spring offers a joyous experience of fragrance, texture, sound and visual stimuli. The heady, dreamy cascades of flowering hawthorn, the myriad leaf shapes, the unreal burst of herbaceous growth, bee hum and birdsong of spring are exciting releases from the drabness of winter. Add to these joys the sight of spring butterflies to increase one’s pleasure in the awakened landscape.

Most of the action occurs within a metre or so of the hedge. Walk into most fields and the biodiversity count plummets. Scientific studies support our impressions of how rich hedgerows are.

According to Lysaght and Marnell (2015) there are 450,000 km of hedgerows in Ireland. Catherine Keena of Teagasc, the Farmers’ Advisory Service, states the figure to be significantly higher at 689,000 km. Sullivan et al. (2017) quotes previous studies that demonstrate the importance of linear features, like hedgerows, for many species. Hedges influence micro-climate, providing shelter and warmth to animals, especially cold-blooded animals such as reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates, including butterflies and moths. Hedges increase connectivity in the farmed landscape by providing warmth, food, shelter and cover to allow animals to move.

The Brown Hairstreak relies on hedges for its life cycle.

The Brown Hairstreak relies on hedges for its life cycle.

Hedges are especially important for butterflies and moths. 65% of Irish butterflies use hedges. Some use hedgerow trees as breeding plants, some use grasses and flowers growing on the warm margins for breeding. In addition, many adult butterflies use hedges as territory, mating stations, nectar sources, flight paths, dispersal routes and hibernation sites. The Brimstone butterfly uses hedgerows for all these reasons, while the Brown Hairstreak uses hedges for breeding, meeting and mating, feeding and as a flight path.

A study by Merckx et al. (2012) found the hedgerow trees and extended width margins locally increased the number of larger moth species (also known as macro-moths) but not abundance. Interestingly, they found that species richness and abundance was not affected by intensive farming, measured by the amount of arable land in the landscape. Both mobile and less mobile larger moths did better when extended width margins and hedgerow trees were present. The benefits of trees in the hedgerow were especially strong for tree-feeding species. Increasing the density of hedgerow trees was recommended to lessen the effects of agricultural intensification. The study underlined the value of hedgerow trees, claiming “a disproportionate effect on ecosystem functioning given the small area occupied by any individual tree”.

The study also found a link between increased macro moth populations and ecosystem functioning (in other words, the higher moth abundance and species richness improves biological community functioning). Why is this? Moths are associated with higher pollinator success, which benefits crops and animals, and moths are an important prey base for a range of species.

A study by Coulthard et al. (2016) showed that hedges are very important flight paths for moths. 68% of moths in the study were observed at 1m from the hedge and of these 69% were moving parallel to the hedge. Hedges are believed to provide the sheltered corridors needed by flying insect in our generally open, farmed landscapes.