In the introduction to my post of last week, Jesmond referred to scientific research into the Small Tortoiseshell. This set me thinking and I would hazard a guess that the Monarch of North America is the most researched butterfly in the world. However, we have our own much-studied butterfly in this part of the world and that is the Painted Lady. This remarkable migrant butterfly has intrigued scientists for centuries and is still the subject of much research.

The BBC devoted an entire programme to the Painted Lady in 2016 entitled “The Great Butterfly Adventure – Africa to Britain with the Painted Lady”. This gets reshown from time to time on BBC4 and may be accessible in other ways. There is a fascinating behind the scenes look at the Natural History Museum in London which has the largest collection of Painted Ladies in the world. The museum was originally built to house the vast collection of Dr Hans Sloane, a 17th-century Irish scientist and collector born in Co. Down, whose collection contains the oldest Painted Lady ever collected. This is preserved in a wonderful scrapbook put together by the Rev. Adam Buddle the botanist after whom the buddleia is named.

The star of this BBC programme is Dr Constanti Stefanescu of the Granollers Museum of Natural Sciences in Catalonia. He is the foremost expert in the world on the Painted Lady and we see him do everything from chasing around netting butterflies in Morocco to dissecting their larvae back in his lab for the purpose of studying their parasitic wasp. I was lucky enough to attend a presentation he gave in the Botanic Gardens in Dublin in October 2013, entitled ‘The incredible journey of the Painted Lady butterfly’, and subsequently exchange an email with him. He is well located as Catalonia is where the first generation touch down when they migrate northwards from Morocco towards the end of March. They don’t just refuel here, they produce a whole new generation. Although these adults will only live about three weeks they breed very quickly. The host plants on which they lay are primarily thistles and mallows but they can use a range of plants, unlike most butterflies, which likely contributes to their success.

Before I acquired a remarkable book ‘The Migration of Butterflies’ by C. B. Williams published in 1930, I was curious as to how much earlier scientists knew about this subject and how could they know? Williams had formerly been an entomologist with the East Africa Agricultural Research Station and at the time of publication was lecturing in Edinburgh University. In addition to his own observations and research, he corresponded with a wide network of scientists and naturalists all over the world long before the advent of computers, the internet or social media. I was surprised at the large number of butterfly references in scientific and entomological publications of 100 years ago and more and newspapers even reported on butterfly topics.

Interest in the subject had picked up in 1879 with the largest migration in Europe for a century when clouds of Painted Ladies ‘cast shadows on the ground’. There was much correspondence during 1879 on the subject of ‘butterfly swarms’. J. H. A. Jenner wrote to Nature in July “With reference to the swarms of butterflies referred to by M. Forel, in NATURE, vol. xx. P. 197, it may be interesting to mention that Vanessa cardui is this year very common in the south of England. This butterfly is known to all English lepidopterists to be ‘periodical’ –in some seasons it occurs in great numbers, in others—perhaps for several years in succession—not one specimen is to be seen.”

There was still some scepticism in the scientific community that insect migration occurred at all. Williams painstakingly accumulated the evidence from recorded observations including many of his own. Two of the key indicators looked for by Williams as evidence for migration are ‘observation of unidirectional flights’ and ‘periodic occurrence’. He logged records and constructed flight charts based on data he collected. He knew that Painted Ladies originated in North Africa and flew northwards, “crossing the Mediterranean with ease” and that they produced new generations in Europe. However, as evidence of return movement was not established, the general belief was that they died out at the onset of winter and we had to wait almost another century before this mystery was solved.

It was cracked at Rothamstead Research Centre in Hertfordshire using vertical-looking radar which detected that the Painted Ladies were flying at a height of over 1,000 metres. No other migrating insects fly at such a height and explains why their return flights are not seen. They calculated that 11 million butterflies arrived in Britain in the spring of 2009 but that 29 million started the journey south that autumn. Rothamstead is the world’s leading centre on insect science and we also see in the BBC documentary some of their other amazing research such as fixing tiny radio antennae to individual butterflies to study their flight patterns using tracking radar and research into how they use the sun to navigate.

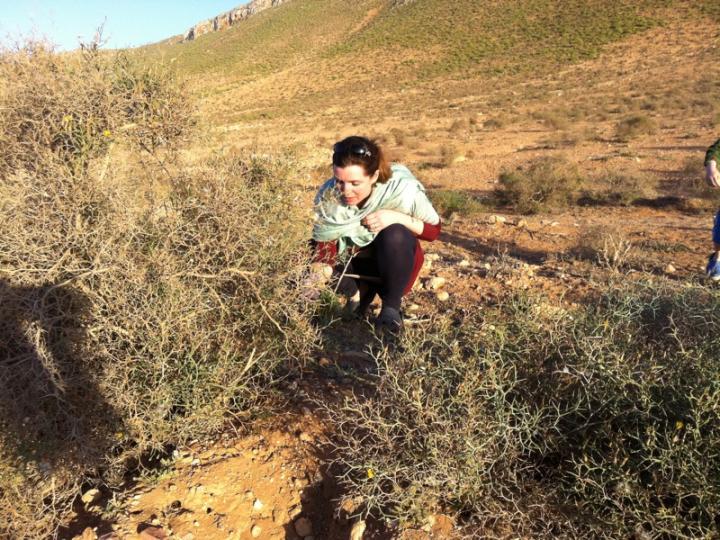

Irish scientists have also researched the Painted Lady. In February 2012 Dr Eugenie Regan, then with the National Biodiversity Data Centre, undertook a field trip to Morocco. Eugenie had collaborated with Constanti on some of his research and was following up on a field trip made by him a month earlier. The aims of the trip were to confirm known breeding sites identified by Constanti, collect larvae to analyse for parasitism and to search for possible new breeding sites. She had limited success with the first two objectives as it was possibly just past the peak pupation period but she had a notable success with the third objective. She found evidence of breeding in the Draa Valley in Southern Morocco on the edge of the Sahara and observed adult Painted Ladies flying in from the south thus raising the possibility that their range extends to sub-Saharan Africa. This has now been confirmed by subsequent studies and Constanti’s team analysed hydrogen isotopes in the wings of butterflies collected in tropical Africa which revealed that most of the autumnal Painted Ladies caught in sub-Saharan Africa had emerged in southern or central Europe and must, therefore, have undergone one of the longest migratory journeys recorded for any insect.

In July 2013 Eugenie and Dr Emily Gleeson of Met Éireann published a paper in the Irish Naturalists’ Journal entitled ‘The Painted Lady (Vanessa cardui L.) migration of 2009 as recorded by the Irish Butterfly Monitoring Scheme and an investigation into the origin of the migration’. The paper describes the Painted Lady migration of 2009 highlighting the large arrival at the end of May. Only a small proportion of these butterflies appear to have successfully reproduced that summer unlike in Britain. Weather data and back trajectories were used to investigate the origin of the May migration and these analyses showed that the butterflies probably travelled through France, England and/or Wales before arriving in Ireland. The next big Painted Lady year was 2019 and Jesmond has documented this in Butterfly Conservation Ireland’s 2019 annual report. The authors acknowledged the contribution of the network of citizen science recorders across Ireland.

There were many forerunners to the modern-day citizen scientist; amateur enthusiasts and naturalists who recorded, kept diaries and published. Some of these were in the far-flung corners of the British Empire as was Williams himself. Sydney B.J. Skertchly wrote to Nature in July 1879:

“Some, at least, of the swarms of V. cardui originate in Africa, one of which I witnessed a day’s march west of Sowakin, in Nubia [modern day Sudan], in March 1869. Our caravan had started for the coast, leaving the mountains shrouded in heavy clouds, soon after daybreak. At the foot of the high country is a stretch of wiry grass, beyond which lies the rainless desert as far as the sea. From my camel, I noticed that the whole mass of the grass seemed violently agitated, although there was no wind. On dismounting, I found that the motion was caused by the contortions of pupae of V. Cardui, which were so numerous that almost every blade of grass seemed to bear one. The effect of these wrigglings was most peculiar, as if each grass stem was shaken separately—as indeed was the case—instead of bending regularly before a breeze. I called the attention of the late J. K. Lord to the phenomenon, and we awaited the result. Presently the pupae began to burst, and the red fluid that escaped sprinkled the ground like a rain of blood. Myriads of butterflies limp and helpless crawled about. Presently the sun shone forth, and the insects began to dry their wings; and about half-an-hour after the birth of the first, the whole swarm rose as a dense cloud and flew away eastwards towards the sea. I do not know how long the swarm was, but it was certainly more than a mile, and its breadth exceeded a quarter of a mile.”

Your own observations can contribute to our knowledge of the Painted Lady. Your records to the Butterfly Conservation Ireland recording scheme is one way of doing this. See https://butterflyconservation.ie/wp/records/ Another way is participation in our garden survey, see https://butterflyconservation.ie/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/National-Garden-Butterfly-Survey.pdf.

Pat Bell, March 2020