Cast your imagination back 125,000 years. The climate then was as warm, on a sustained basis, as it has been in the past decade. Where Trafalgar Square stands today, alligators, hippopotami, and lions roamed the savanna while elephants grazed the banks of the Thames. Today, Sir Edwin Landseer’s bronze lions guarding Nelson’s column grandly survey the Square where the wildlife consists mundanely of feral pigeons.

Imaginative indulgence conjures dreams of restoration ecology, beloved by hankerers for the recovery of ecosystems deficient in parts of the puzzle. In Ireland, such projects are usually concerned with iconic apex predators, such as the Grey Wolf, Red Kite, White-tailed Sea Eagle, and Golden Eagle. The latter three have been introduced to Ireland while the Grey Wolf is busy recovering lost territory throughout western Europe, under its own steam, but benefiting from the ban on poisoning and hunting that brought the animal to the edge of oblivion in most of Europe in the late 1970s.

But clocks are not easily turned back, and as the Covid pandemic demonstrated, we are not in control. The greater powers, the wrath of whom we have provoked, are in the ascendant. We are reactors, employing a scattergun approach to problem-solving that Manchester United’s transfer negotiator John Murtough would recognise, but be embarrassed by.

Our vulnerability to greater power than our meagre selves was spelled out to the cabinet committee on the environment and climate change in early May 2022 by Professor Peter Thorne, a lead author on the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and one of the world’s leading climate experts.

Professor Thorne told the Climate Committee, which consists of the Taoiseach (Prime Minister), Tánaiste (deputy Prime Minister), Ministers of Public Expenditure and Reform, Social Protection, Agriculture, Climate Action, Tourism and Housing, that to keep the temperature below 1.5 Celsius above the pre-industrial era temperature, we need net emissions to reach zero by 2050. This requires halving methane emissions and getting carbon emissions to net zero.

You probably knew that. But then the devastating news was delivered that stabilisation of all effects of climate change is impossible in the next few centuries. Sea levels will rise by five metres.

There is nothing we can do to change this.

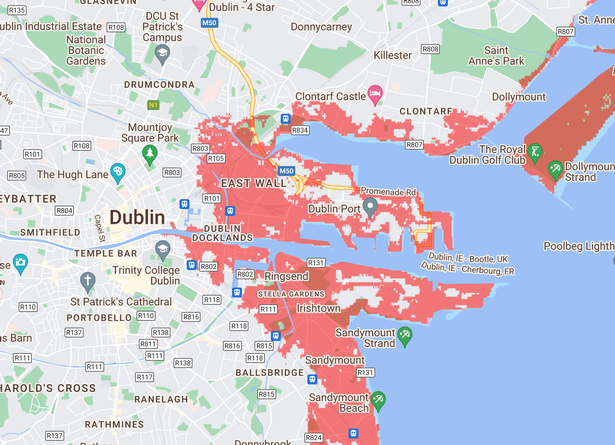

If you live in Cork City, Limerick, Galway, or Belfast you are in peril, especially if you are in junior infants’ class, typically a five-year-old. Here is what the sea level rise means for Dublin.

By the time our five-year-olds reach old age, Dublin will no longer contain Sandymount, Blackrock, Monkstown, Sandycove, Dun Laoghaire, and Ringsend on the south side and Malahide, Clontarf, Portmarnock and Sutton on the north side of the River Liffey. The Hill of Howth will be an island and there will be no Bull Island. The Liffey, by then hundreds of metres in width, will enter the sea at Phoenix Park. Dublin Bay will stretch from Cabra on the north side to Donnybrook to the south. The flooding will reach Lombard Street, near Trinity College.

The past 10,000 years have seen a remarkably stable global climate, allowing humans to develop from nomadic hunter-gatherers to settle in great urban centres facilitated by the industrial and agricultural revolutions. This climate stability is rapidly unraveling, according to Professor Thorne.

It will be worse elsewhere, such as on the Indian sub-continent, but we will feel the shocks, directly, economically, and in human terms, with mass migration to this country. We are at the edge of human livability in some areas already, such as the Horn of Africa, and this year, in parts of India.

If we are stupid enough to go to three Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures by the time our Junior Infants reach advanced old age, and this is where we are heading with current emission levels, 75% of all the planet’s biodiversity will be lost. Imagine what such a world would look like.

Many of our familiar plants and animals have ceased to exist. The photographs in The Irish Butterfly Book will likely show several extinct species. I wonder if the Wall Brown, Hedge Brown, Small Heath and Large Heath will still exist. These species are already in serious decline, and climate change and issues driving climate change are among the causes. The extinction list is also likely to contain the species that need well-drained skeletal soils: Dingy Skipper, Small Blue, and Pearl-bordered Fritillary.

There are studies concerning the link between the warming climate and butterfly declines. There are indications that a combination of climate change and pollution is damaging the habitat of the Wall Brown. Kurze et al. (2018) suggest that it is very likely that nitrogen enrichment from fertilisers is killing some species larvae on farmland while Habel et al. (2015) suggest that increased plant growth rates arising from nitrogen deposition, increased rainfall and climate warming are cooling the micro-climate at larval sites, driving declines of species that depend on nutrient-poor habitats.

A study that looked specifically at the Wall Brown’s decline, Impact of nitrogen deposition on larval habitats: the case of the Wall Brown butterfly Lasiommata megera by Klop et al. (2014) found that nitrogen addition to potted foodplants on which larvae were fed had beneficial effects on larval development. However, the study found the influence of nitrogen deposition on larval micro-site cooling the most likely reason for the decline: “The raised levels of green plant biomass under excessive nitrogen availability leads to an increase of both shading and green: dead ratios in the vegetation, which should be expected to result in a cooling of microclimatic conditions.”

Like Habel et al. (2015), Klop et al. (2014) believe the decline of heat-loving species “could be explained by a combination of excess nitrogen and climatic warming, with both factors enhancing plant growth in early spring and reducing the availability of warm microclimates.” Elevated temperatures at the larval micro-site, typically arising from a combination of unshaded bare patches of ground containing sparse foodplant vegetation and warm, dry, dead plant litter are critical to the caterpillar in spring when air temperatures are cool. If these findings are correct, geographical scale pollution reduction measures must be implemented along with measures to tackle climate change. If not, we could be lamenting the extinction of one of our formerly common and widespread butterflies.

However, in such a devastating context that Professor Thorne outlined, the fate of our butterflies may seem of small consequence, a trivial footnote to a doomsday of mass extinction and global crisis for mankind, with continued human existence at stake.

Thorne stated that a brief and closing window exists to secure a livable future if concerted global action takes place.

But the past decade has had the highest greenhouse gas emissions in human history.

Professor Thorne stated that technological solutions exist to produce low emissions, but investment, which is available, and leadership, are needed.

How, then, did the cabinet committee react to Thorne’s presentation? A few polite questions later, the ministers began to discuss sectoral contributions to emission reduction targets. The Irish Government reacted by producing, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) report published three weeks (May 31, 2022) after the briefing, an emissions policy that adds up to 28% of greenhouse gas (carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide) reductions by 2030, not the required 50%.

When RTE’s HOT MESS programme sought an interview with any of the ministers who attended the briefing, no minister was made available.

Before we blame the Government, let’s look at ourselves. Do you want to sell your second car, get rid of your beloved SUV, pay higher taxes, and pay more for food?

I doubt it. But politicians need to lead public opinion, not follow it. Opportunities for leadership exist. Jim Hacker, the fictional minister in the British comedy, ‘Yes, Minister’, when asked to defy public opinion for the good of Britain, responded, “I am their leader. I must follow them.”

No more of that.

Policies that are unpopular now, will become more popular, over time, as people realise how crucial they are. Let us act so we don’t run out of it.

Sources

Dublin Live (2022) Terrifying flood map shows what Dublin will look like by 2030 https://www.dublinlive.ie/news/dublin-news/terrifying-flood-map-shows-what-23608348 (Accessed 19 August 2022)

EPA (2021) EPA Greenhouse Gas emissions projections highlight the need for urgent implementation of climate plans and policies. Available at: https://www.epa.ie/news-releases/news-releases-2022/epa-greenhouse-gas-emissions-projections-highlight-the-need-for-urgent-implementation-of-climate-plans-and-policies-.php (Accessed 19 August 2022)

Habel, J., Segerer, A., Ulrich, W., Torchyk, O., Weisser, W., and Schmitt, T., (2015). Butterfly community shifts over two centuries. Conservation Biology, Volume 30, No. 4, 754–762, accessed 28 December 2020, https://conbio-onlinelibrary-wiley-com.jproxy.nuim.ie/doi/epdf/10.1111/ cobi.12656

Harding, J.,(2021) The Irish Butterfly Book, privately published, Maynooth.

Klop, E., Omon, B. & Wallis DeVries, M.F. (2015) Impact of nitrogen deposition on larval habitats: the case of the Wall Brown butterfly Lasiommata megera. Journal of Insect Conservation 19, 393–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-014-9748-z

Kurze, S., Heinken, T. & Fartmann, T. Nitrogen enrichment in host plants increases the mortality of common Lepidoptera species. Oecologia (2018) 188: 1227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442- 018-4266-4

Natural History Museum (2014) London’s Wild Times: Past and Present https://www.nhm.ac.uk/natureplus/blogs/whats new/tags/britain_one_million_years_of_the_human_story.html (Accessed 19 August 2022)

RTE (2022) Episode 12 Getting Hotter. Available at: https://www.rte.ie/radio/podcasts/22110709-ep-12-getting-hotter/ (Accessed 19 August 2022)

World Wildlife Fund (2021) The Return of the Wolf in Europe https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/the-return-of-the-wolf-in-europe#:~:text=Wolves%2C%20along%20with%20other%20predators,effort%20to%20prevent%20livestock%20predation. (Accessed 19 August 2022)