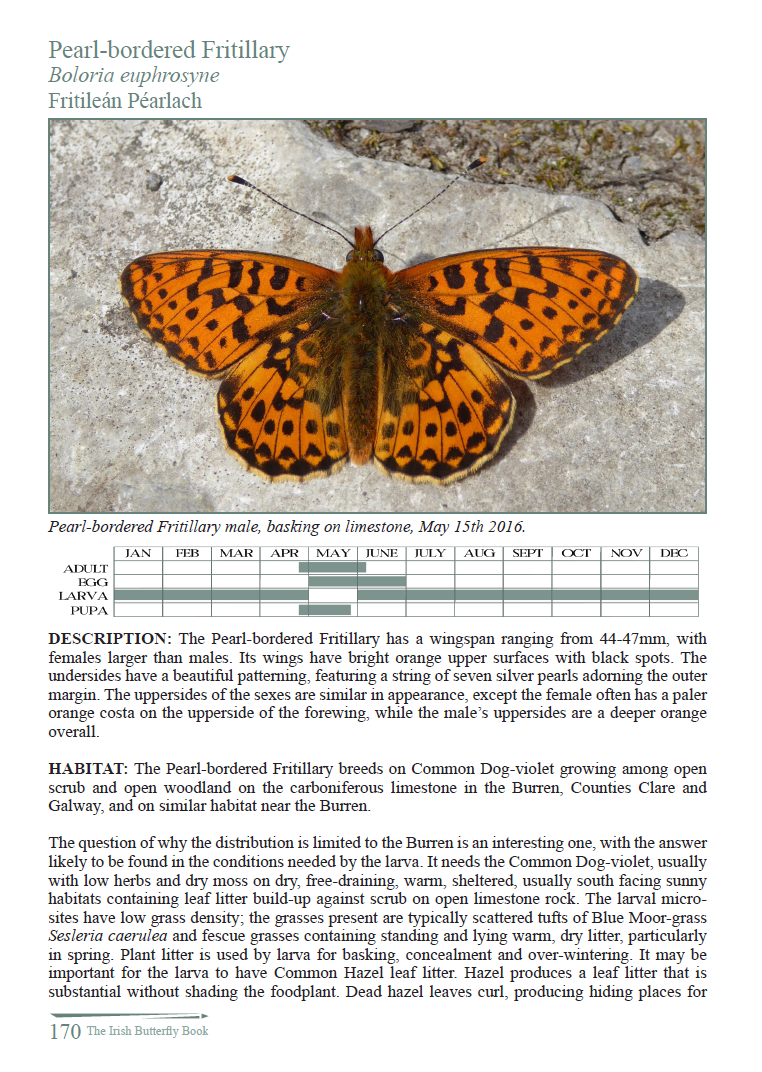

Submission to the Citizens’ Assembly on Biodiversity Loss by Butterfly Conservation Ireland

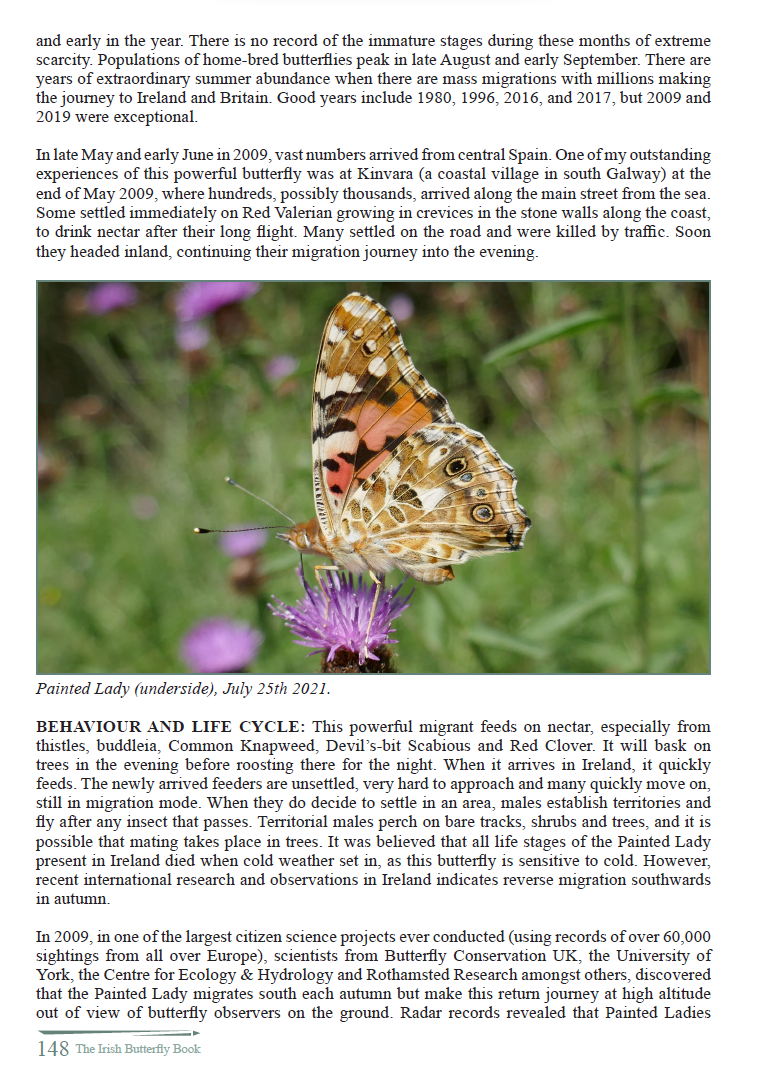

Executive Summary

The most urgent matter is preventing any further damage to our protected habitats. This requires monitoring protected areas and applying the highest penalties on anyone who damages our designated habitats. A programme of eradication of non-native biological threats to our habitats should be rolled out nationally, especially to target invasive, non-native Fuchsia, Montbretia, Rhododendron, Cherry Laurel, Japanese Knotweed, and Himalayan Balsam.

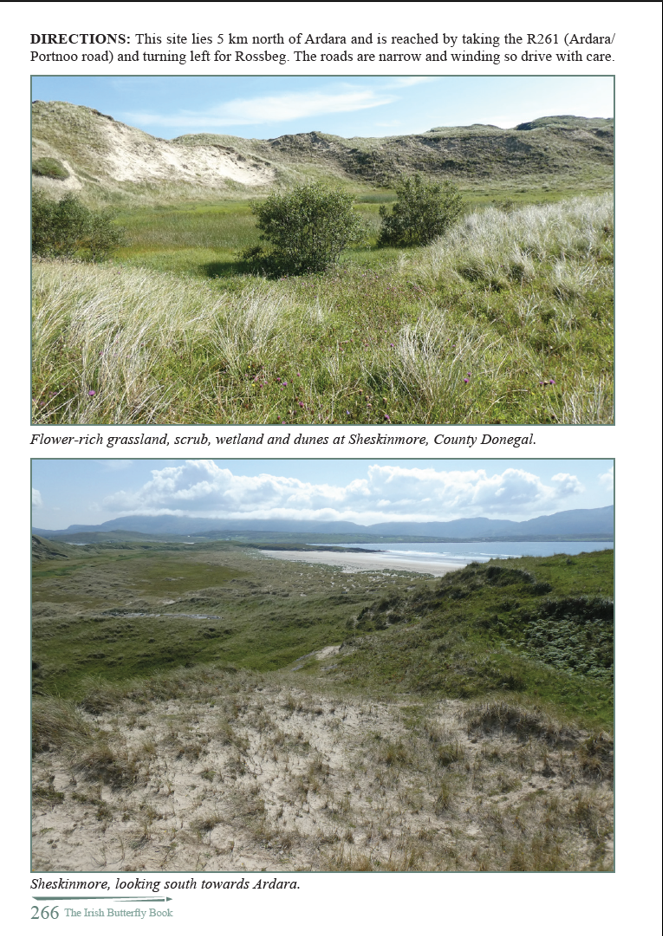

Extending protected areas is needed to adequately protect species and habitats and to meet the need to protect 30% of our land under the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030. A new National Park proposed for the Ballydermot area in northwest Kildare and east Offaly, the first in the midlands and the first to be located on raised bog habitat, will help to meet Ireland’s commitments to protect nature, tackle pollution threats and climate change.

Scientific research is needed to determine the causes of decline of our rarest butterflies and moths, and to calculate the Favourable Reference Value to judge how many sites should be protected. Management plans for such sites and for all protected lands and marine areas should be produced and implemented.

Semi-natural grasslands must be protected and farmed correctly to maintain and enhance their conservation status. Teagasc and the National Parks and Wildlife Service have crucial roles to play in supporting farming for nature.

Peatlands must be protected from any further drainage and depletion. Peat extraction and importation should be banned. Industrialisation and afforestation of peatlands must be prevented and reversed, and peatlands restored as fully as possible.

Clean/renewable energy generation should be promoted to reduce pollution, but associated infrastructure must be located in appropriate sites, and must not impact negatively on threatened habitats or species.

The area under native woodland must be greatly extended using native seed obtained from indigenous sources.

Hedges and extended field margins should be correctly managed and new hedges, comprising native species from indigenous sources, planted to reduce field sizes and create connectivity across the landscape. New legislation to prevent hedge removal may be needed.

Agricultural pollution must be greatly reduced to avoid further damage to our terrestrial and aquatic habitats.

Environmental education should be introduced as a discrete element across the primary and second level curricula, and training of ecologists reviewed to re-focus on the skills and knowledge needed to identify species and ecological conditions required for our most threatened species.

A restructured National Parks and Wildlife Service is required to discharge its remit to conserve, designate and advise on priority species and habitats, to implement nature conservation legislation and policies, to manage state-owned areas reserved for nature and promote awareness of natural heritage and biodiversity.

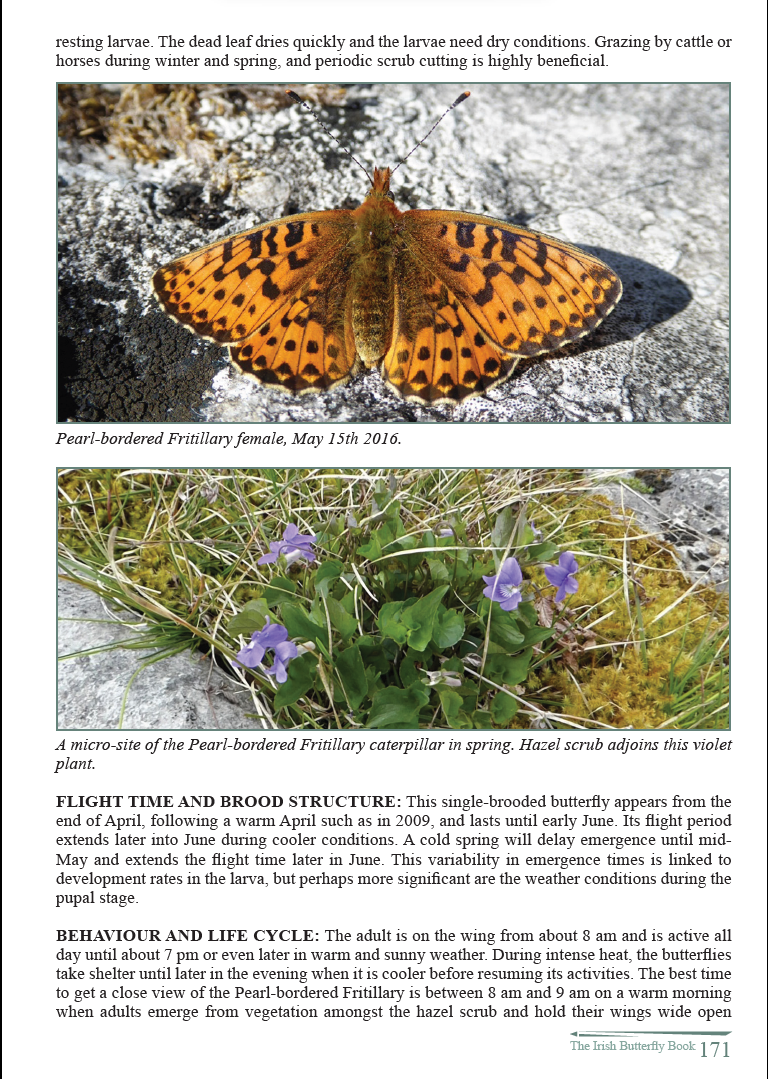

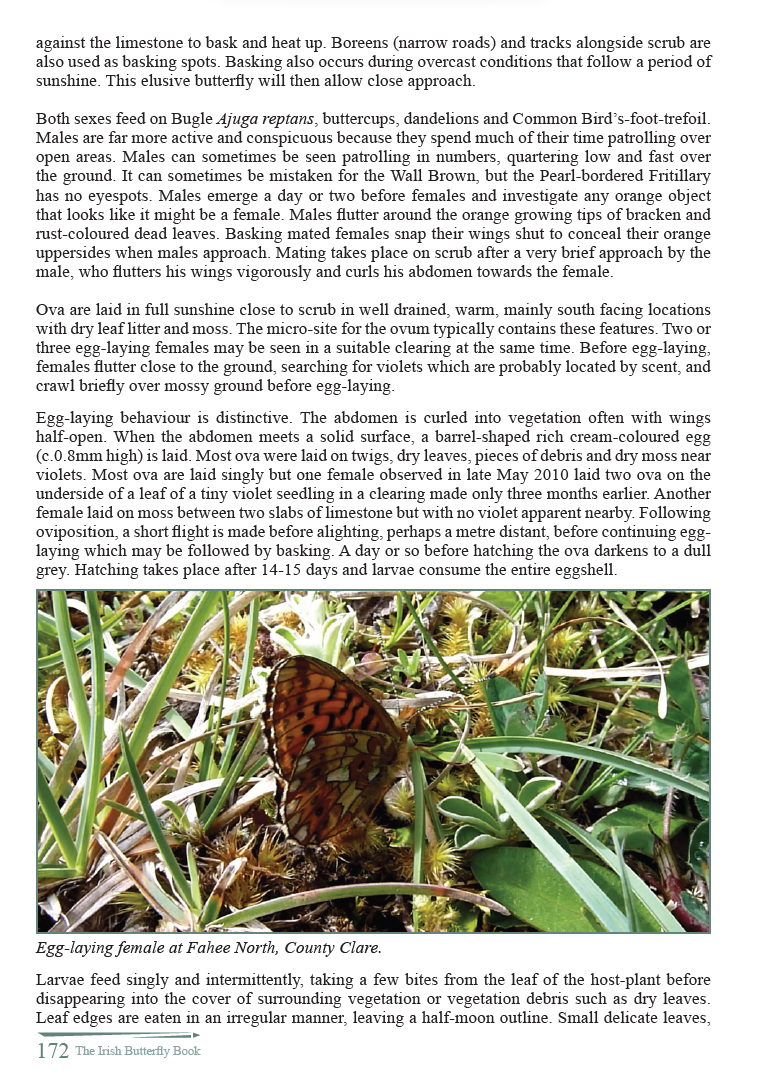

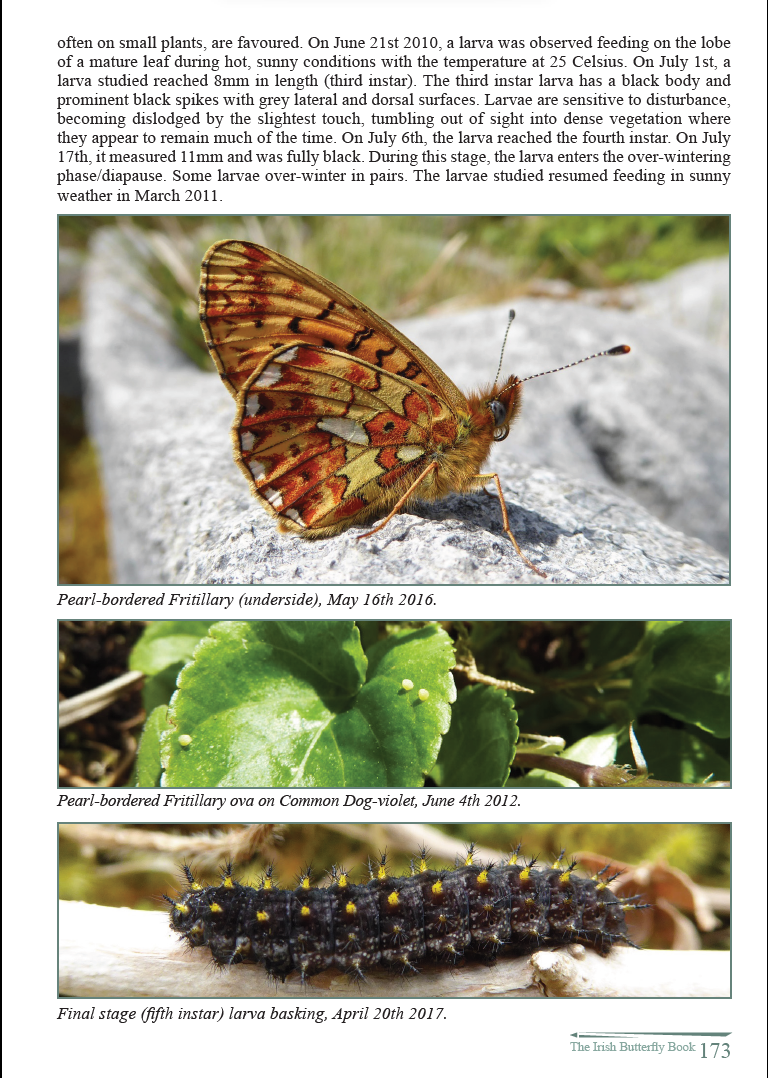

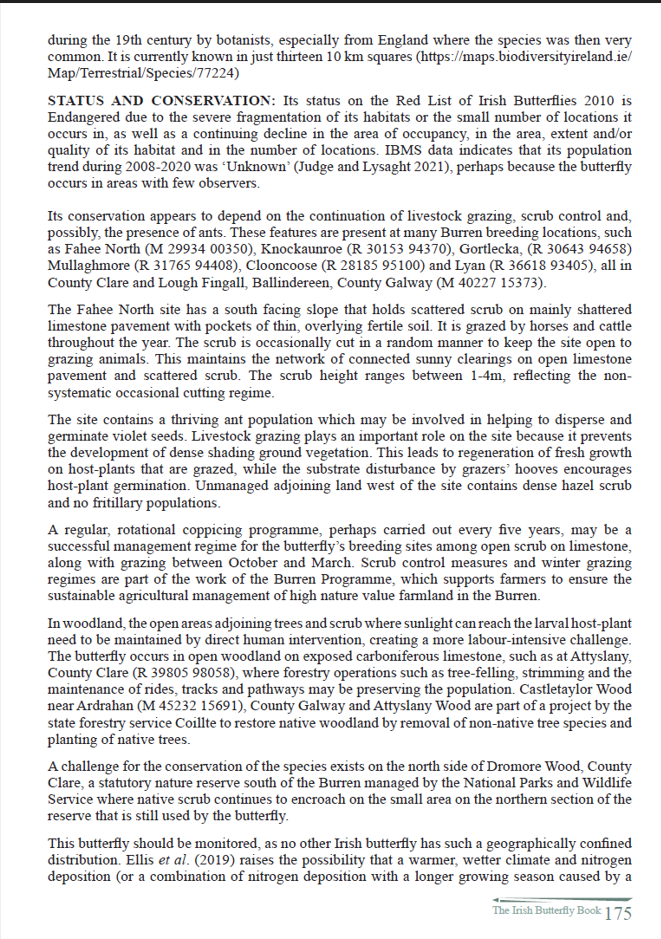

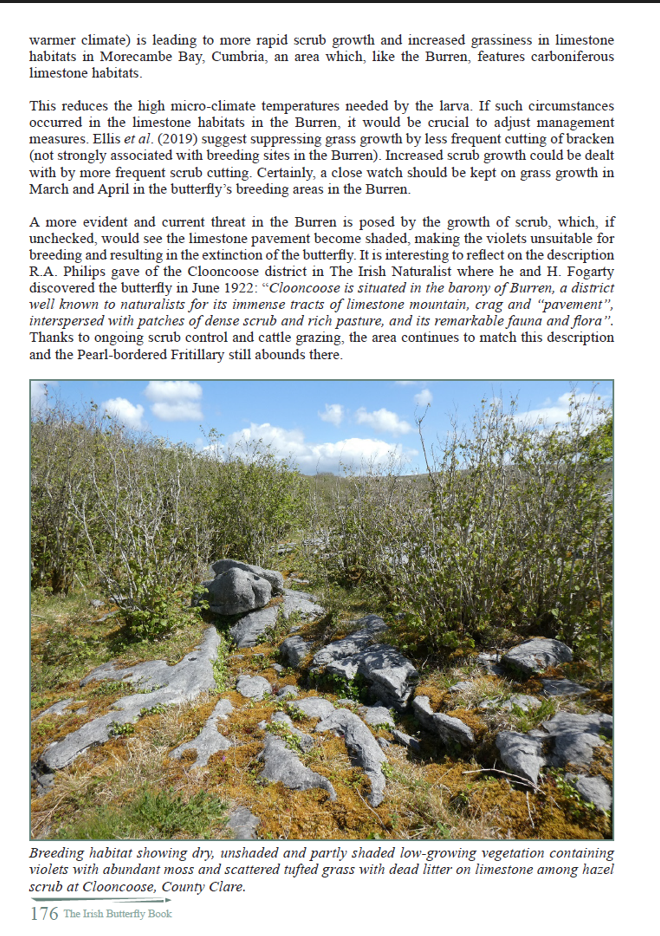

What path will our environment take? Semi-natural grassland, limestone pavement, scrub and woodland in the Burren, County Clare.

What path will our environment take? Semi-natural grassland, limestone pavement, scrub and woodland in the Burren, County Clare.

Introduction: The Context of this Submission

The Citizens’ Assembly on Biodiversity Loss has much loss to consider. The following presents Butterfly Conservation Ireland’s view on the biodiversity circumstances pertaining to Ireland and its implications for butterflies and moths and general biodiversity, and actions that can be taken to attempt ameliorate or remedy the environment degradation that besets this country.

According to the Natural History Museum in London, out of all EU countries (including the UK) only Malta is worse in terms of biodiversity loss than Ireland. This puts Ireland in the bottom 10% of countries globally in terms of biodiversity intactness. [1]We have no natural habitats left, and many of our semi-natural habitats continue to suffer neglect and direct removal. The greatest reason for biodiversity loss in Ireland is the change in land use, mostly for agriculture, especially since Ireland joined the EEC in 1973. Other drivers include invasive non-native species, afforestation, pollution, and climate change.

- The Problems

Grasslands

Many of our butterfly and moth species depend on semi-natural grassland habitats. Grassland butterflies and butterflies associated with other habitats are excellent indicators of the health of the environment. Data on the abundance of most of Ireland’s butterfly species is easily recorded, given the high visibility of butterflies and their popularity with the public. The Irish Butterfly Monitoring Scheme run by the National Biodiversity Data Centre in Carriganore, Waterford, presents the data in annual reports, which are fed into the European Grassland Butterfly Indicator. The EU Grassland Butterfly Indicator is one of the indicators of the status of biodiversity in the European Union. It is an abundance indicator based on data recording the population trends of seventeen butterfly species in 16 EU countries.

The European Grassland Butterfly Indicator is based on the national Butterfly Monitoring Schemes (BMS) in 19 countries across Europe, most of them in the European Union. The Irish Butterfly Monitoring Scheme data is represented in these findings.

The EU Butterfly Indicator for Grassland species: 1990-2017 showed the following grassland species that occur in Ireland have declined across Europe, including Ireland: Wall Brown Lasiommata megera (strong decline), Small Heath Coenonympha pamphilus, Small Copper Lycaena phlaeas and Common Blue Polyommatus icarus (moderate decline). The trend status for the Marsh Fritillary, our only legally protected butterfly, was ‘uncertain.’[2] The data from Ireland supports the decline trend.

The results of the Irish Butterfly Monitoring Scheme 2021 show, as they did in 2020, that there was a moderate decline in the number of butterflies flying in 2021 when compared the baseline year of 2008 (the start of the monitoring scheme). In terms of the individual species trends, none of our butterfly species showed a positive trend with only two species having ‘stable’ trends. All other species showed either ‘declining‘ or ‘uncertain’ trends when compared to the baseline year of 2008[3].

While this decline exists across the EU, it is worse in Ireland. Furthermore, being an island, Ireland is isolated from European butterfly populations and a rescue effect, with individual butterflies migrating to areas that have again become suitable, is unlikely as most of our butterfly species are non-migratory.

Considerable significance should be interpreted in the decline of our most abundant species, the Meadow Brown Maniola jurtina which showed a trend 2012–2021 of moderate decline (-70%). The reason that this is especially significant is that this is a widespread species with low specificity in its grassland habitat requirements. It breeds on any semi-natural grassland even when fertiliser is applied. When an undemanding species is declining, widescale environment degradation is indicated[4].

The problems affecting grassland habitats in Ireland and across the EU are known from the Article 17 Reports provided by EU member states, including Ireland, to the European Commission. Under Article 11 of the EU Directive on the Conservation of Habitats, Flora and Fauna (92/43/EEC), commonly known as “the Habitats Directive”, each member state is obliged to undertake surveillance of the conservation status of the natural habitats and species in the Annexes and under Article 17 to report to the European Commission every six years on their status and on the implementation of the measures taken under the Directive. In April 2019, Ireland submitted the third assessment of conservation status for 59 habitats and 60 species (including three overview assessments of species at a group level).

The most important grassland habitats for Ireland’s butterflies and the assessment of their conservation status in the 2019 report are: machair (Inadequate), Marram Dunes/White Dunes (Inadequate) Fixed Dunes/ Grey Dunes (Bad), Calcareous Grassland/Orchid-rich (Bad), Molinia Meadows (Bad), Lowland Hay Meadows (Bad), Alkaline Fens (Bad).[5] The report provides reasons for the assessments. The most cited reason for a negative rating is agricultural intensification (fertiliser use). Other causes mentioned are inappropriate grazing, land abandonment (where farming that had been beneficial has ceased), drainage, disturbance, and afforestation.

The reason for butterfly and moth declines and general biodiversity loss is linked, not with climate change but with the condition of habitats. Analysis of Article 17 Reports submitted by EU member states carried out by Butterfly Conservation Europe noted the following problems with protected grassland habitats. The prevalence of threats to grasslands described in the Article 17 reports show that abandonment of grassland management (no grazing or cutting of vegetation) is the chief threat, with 385 mentions in the reports. The second most prevalent is mowing or cutting of grasslands at 254 mentions, followed by overgrazing (240), natural succession resulting in a change in the species present (148), use of chemicals to protect certain agricultural plants (111), afforestation (110), conversion from one type of farming use to another (87), conversion from other land uses to housing, settlement and recreational use (78), use of synthetic fertiliser on farmland (76), collection of wild plants and animals (72) and conversion to other forest types including monocultures (70)[6]. All these factors, except the collection of wild plants and animals, applies to Ireland’s grasslands. This information is derived from EU member state Article 17 reports, so the causes of decline across Ireland (and the EU) and the improvement steps needed are known. This needs to start in protected areas and in any new protected areas.

Peatlands

The butterfly species monitored for the grassland butterfly indicator are mainly widespread species. There are some habitat specialists dependent on habitats that are less common in our landscapes or that were common but have since been significantly altered or destroyed. One example is the Large Heath butterfly Coenonympha tullia which relies on bogs containing large areas of characteristic wet bog vegetation. Widescale peatland drainage and harvesting operations have impacted populations greatly but calculating distributional change by mapping at 10km resolution carried out by the National Biodiversity Data Centre fails to show the population decline that has occurred in Ireland over the last half-century or so. Given the specialised habitat requirements of this species, without habitat restoration projects which specifically recreate favourable breeding conditions for Large Heath, the conservation outlook for the species, (ranked ‘Vulnerable’ on the Irish Butterfly Red List[7] ) remains poor in Ireland.

However, most bogland is so severely degraded that recreating these conditions within any reasonable time frame is impossible, even when re-wetting is applied. The habitats produced on re-wetted bogs are typically reed swamp, poor fen and open water, unsuitable for the Large Heath and a range of butterfly and moth species, and for many other high bog specialist species.

The protected raised bog areas that remain continue to deteriorate. According to the 2019 Article 17 Report,

The main pressures on active raised bog are peat extraction, drainage, afforestation and burning. Climate change is also considered to pose a threat in the future. The Overall Status of the habitat is Bad and deteriorating, unchanged since the last assessment.

If this continues, species that rely on this habitat type will disappear.

Scrub and Woodlands

Aside from grasslands, marsh, and bogs, the other main butterfly habitats are scrub and woodland. These often exist as mosaics with grasslands and wetlands. Ireland is deficient in native woodland. The remnants are generally hillside woods in Counties Kerry and Wicklow with small patches on old estates or inaccessible sites such as lake islands and eskers. Few native woods on fertile soils remain in Ireland. Plantations of non-native species, undertaken especially on what is considered marginal farmland and upland blanket bogs, not only removes important habitat but creates woodland that is unsuitable for Ireland’s biodiversity, including butterflies and most moths.

The total national area of forest is about 10% of the land surface, less than one-fifth of which consists of native woodland.[8] The result is that woodland butterflies are generally thinly distributed because their habitats are absent from many areas. The Purple Hairstreak butterfly Favonius quercus which requires native oak trees, is known from a single location in County Dublin (Phoenix Park) and County Kildare (Leixlip Castle). The species has a restricted distribution by the scarcity of habitat that would, without human interference, be common across our landscapes.

The pressures that affect the annexed habitat, Old Oak Woodland (Habitat Code 91AO) are non-native species such as Rhododendron ponticum, Cherry laurel Prunus laurocerasus and Common Beech Fagus sylvatica and overgrazing by deer. These impacts severely reduce tree regeneration, which is essential for the long-term viability of woodlands in conjunction with the continued fragmentation of remaining stands, lead to an Overall Status of Bad with a deteriorating trend[9]. The aim of the development of native woodland should be to have woodland throughout the landscape, connected by well managed hedgerows and scrub, and to have native woodland large enough to ensure that woodland animals and plants can move across the landscape, and woods large enough for people to get lost in.

Hedgerows

Hedgerows usually contain native trees and are very important for butterflies, moths, and biodiversity generally, especially in our farmed landscapes. In Ireland, hedgerow trees and shrubs are mainly Common Hawthorn, Common Blackthorn, Common Hazel, Common Holly with gorse and Grey Willow commoner on wetter soils. Other plants that occur in hedges are Common Yew, Common Spindle, Common (Purging) Buckthorn, and occasionally Alder Buckthorn. Many hedgerows contain trees, especially Pedunculate Oak, Rowan, Common Ash, and Common Beech. 65% of our butterflies and many of our moth species are associated with hedges and extended field margins. Hedges that have large native trees that are allowed to grow are especially valuable[10].

Severe and widescale cutting of hedgerows is damaging to biodiversity. many species that breed on hedges lay eggs on the newest growth. Unfortunately, it is this outer part of the hedge that is removed by cutting. The Brown Hairstreak butterfly Thecla betulae is extremely vulnerable for this reason, and Berwearts and Merckx (2010) report studies that found that annual mechanical cutting of hedges removes 80-99% of Brown Hairstreak eggs. A rotational cutting system that involves cutting one-third of the hedgerows in an area each winter resulted in the butterfly’s longer-term survival.

Even more serious is the removal of hedgerows by farmers who want to increase field sizes. Outside protected areas, this can be done between August 31st and March 1st. Given the importance of hedgerows to butterflies, moths, and many other species, our landscape cannot afford such losses. Another damaging though smaller-scale practice is the replacement of hedgerows comprising several native species with a single species hedge, often non-natives such as Common Beech, laurel, leylandii, among others. In some parts of the west, non-native fuchsia hedging has become naturalised, along with Montbretia, disfiguring the landscape, displacing native plant species and reducing biodiversity, including in our most important habitats, such as in the Burren region. These alien species are of much less value because they have not co-evolved with the other species naturally present here.

Pollution Threats

The findings in a German study by Habel et al. (2015) entitled Butterfly community shifts over two centuries looked at the impact of atmospheric nitrogen loads and climate change over the period 1840-2013. The study found that high rates of atmospheric nitrogen deposition (from exhaust emissions, the burning of fossil fuels, wood, industrial incineration and the application of nitrate fertilisers) change nutrient-poor ecosystems, resulting in the replacement of plants in nutrient-poor habitats with plants that enjoy soils enriched with nitrogen. This results in butterflies that depend on nutrient-poor habitats, such as limestone grassland and heathland, disappearing, leaving a smaller number of butterfly and moth species that are adapted to plants containing high nitrogen levels.

The study further suggests that while habitat generalists (like the Peacock butterfly Aglais io) have benefited from increasing temperatures, habitat specialists have been negatively affected by increasing temperatures and rainfall. These effects may be explained by increased vegetation growth rates triggered by the combination of increased moisture, temperature, and atmospheric nitrogen. Greatly increased vegetation growth may also explain the apparently paradoxical situation that heat-loving species are declining in response to increased temperatures. However, higher vegetation growth rates, fostered by the combination of increasing plant nutrients, precipitation, and higher temperatures may produce a cooler and more humid microclimate close to the soil. The environment just above the soil is of particular importance in the development of the larvae of many butterfly species, such as the Small Heath and Wall Brown. Eeles (2019) [11]reports elevated levels of carbon dioxide which increases larval development times as another possible reason for the decline in the Small Heath.

The Small Heath is a widespread butterfly across Europe and attention is mostly focused on much less widespread species that are judged to require special protection. However, the decline in widespread grassland butterflies should set the alarm ringing, the proverbial canary in the mine. Unless the drivers of climate change are tackled, site protection may be insufficient save some of our more sensitive biodiversity over the longer term. However, the immediate priority is to deal with the damage being directly caused to our semi-natural habitats.

- Recommendations

Solutions to be tailored to Species’ Habitats

It is impossible to protect butterflies, moths, or any animal or plant group without protecting its home.

We have the data and scientific knowledge to identify new areas that require protection under the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030 which aims to protect 30% of the land area of the EU. Often the current protected areas are too small, and not well managed. Such distribution data and knowledge of the needs of specialised butterflies (butterflies with highly specific habitat needs) can be applied to expand protected areas or create new protected areas, such as former Bord na Móna peat extraction bogs, including the Ballydermot Bog Group area in northwest Kildare, a large wilderness area very rich in biodiversity, currently proposed as a new National Park by Ireland’s conservation NGOs, including Butterfly Conservation Ireland, Birdwatch Ireland and the Irish Peatland Conservation Council[12].

For protected habitat specialist butterflies the approach being used is to calculate the Favourable Reference Value for the population to judge how many sites must be placed under protection. To calculate Favourable Reference Value, required viable population size or species-specific or habitat type-specific features such as habitat suitability or required area for proper functioning are considered (Bonelli et al. 2021). Such an approach has been described which may protect some of the rarest species in Ireland possibly those listed below[13].

For rare species, such as the White Prominent Leucodonta bicoloria, Irish Annulet Gnophos dumetata, Sandhill Rustic Luperina nickerlii and Pearl-bordered Fritillary Boloria euphrosyne, specific action plans are needed to cover issues such as monitoring population size, high-resolution distribution data and management of protected areas. Some of the management carried out under agri-environmental schemes do not give sufficient protection to scrub, which is often removed to increase the area of high nature value grassland, such as Calcareous /Orchid-rich Grassland. For some species, a mosaic of scrub and grassland is vital.

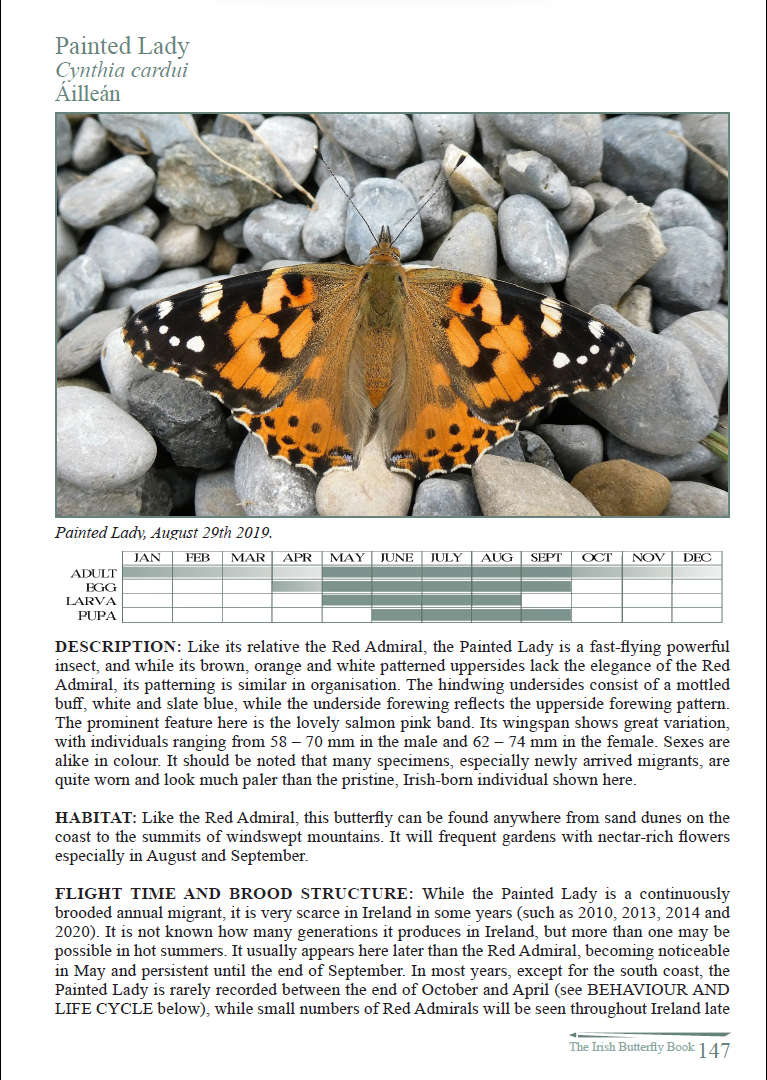

A further approach that can be applied in Ireland is the umbrella approach. Some habitats regarded as priority habitats under the EU Habitats’ Directive such as Calcareous /Orchid-rich Grassland (EU Habitat Code 6210) are butterfly-rich. By identifying areas of this habitat containing endangered butterflies protected under the EU Habitats’ Directive, such as the Marsh Fritillary, a case can be made for including such areas within the enlarged protected areas required under the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030. Protecting habitats for the Marsh Fritillary protects many other species, making the Marsh Fritillary an umbrella species.

For species that appear to remain widespread, but which are suffering from changes such as changing farming practices, we need to work to persuade farmers to adopt measures to protect the habitats. Beautiful, charismatic species like the Small Copper should be used to promote protective practice, using funding from the CAP and other sources. Agricultural intensification is a great threat to this and many butterflies.

Some species, like the Dark Green Fritillary Speyeria aglaja and Marsh Fritillary need a different approach. The larva needs structured grassland vegetation with leaf litter. Populations are being lost from protected sites because of natural succession. Action plans need to be written with a clear management prescription.

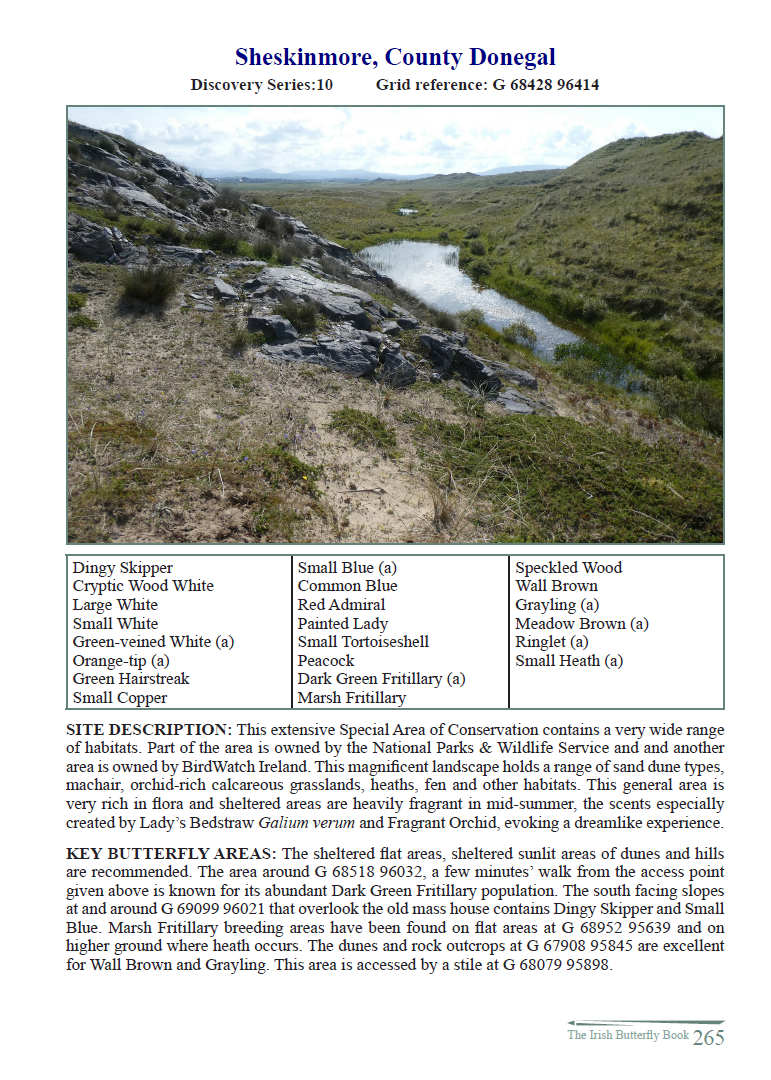

Management and monitoring (especially the use of citizen science), as well as protection from damaging activities are key to butterfly recovery. We suggest integrating the Butterfly Monitoring Scheme with specific guidelines for monitoring species listed in the Habitats’ Directive (in Ireland’s case, the Marsh Fritillary, currently under-monitored here). This approach requires working with citizen scientists and experts. While Butterfly Conservation Ireland, the Irish Peatland Conservation Council, and the National Biodiversity Data Centre monitor the Marsh Fritillary, we simply do not have enough transects (fixed-route walks carried out annually) to monitor this butterfly. A serious effort to apply the Favourable Reference Value to assess the Marsh Fritillary’s populations in landscapes important for its conservation, like the Burren, County Clare and Galway, Sheskinmore in County Donegal and Ballydermot in County Kildare, should be made through the National Parks and Wildlife Service to increase the protected areas that Ireland needs to pledge to the EU by the end of 2022 to help to address the biodiversity crisis afflicting this country.

If applied across our landscapes these measures will be of great value, but they may not be adequate to protect butterflies and biodiversity in the longer term. Most of our landscapes will not be strictly protected and even strictly protected areas will not benefit fully from these measures in the absence of much wider changes in how society operates because pollution is playing a role in the loss of some butterfly populations.

Grasslands

The correct management of our grasslands begins by not destroying any more semi-natural grassland. Because most of our land is farmed, the role of farmers is vital, and the role played by the farm advisory service, Teagasc (The Agricultural and Food Development Authority), is crucial. Teagasc has an advisory and instruction/education role. Unfortunately, it advises farmers to apply pesticides, herbicides, and fertilisers to their land, which destroys biodiversity, increases pollution, and drives climate change. It also promotes or has promoted single-species swards, devastating for most biodiversity. When Butterfly Conservation Ireland wrote to Teagasc to draw attention to research on the impact of nitrates on the mortality of some of our grassland butterflies[14], and offer our help to research nitrogen tolerance, our letter went unanswered. Teagasc must be much more responsive to ecological concerns, and not simply directed to ever-increasing production.

In some areas, farmland is being abandoned, which can result in improved biodiversity outcomes for a short time but eventually leads to habitat change and reduced biodiversity. Scrub and woodland follow with some woodland often comprising non-native self-sown conifers such as Lodgepole Pine.

Biodiversity-led agri-environmental programmes with well-researched results-based outcomes may benefit farming in areas of low agricultural productivity. Re-wetting drained farmland to restore habitats such as hydrophilous tall-herb swamp and marsh, with low intensive grazing using traditional cattle breeds, is highly sympathetic to biodiversity.

Peatlands

The destruction of peatlands is the most egregious affront to the integrity of our landscapes. The race to drain, extract and burn peat is the gravest offence to our environment since World War II. The damage is done and is effectively irreversible on most peatlands where mechanised, large-scale exploitation occurred. All that can be done is to properly protect the remaining designated peatlands, applying the full penalties allowed to those who destroy legally protected habitats. We want the state to purchase bogs that are capable of regeneration instead of paying owners and holders of turbary rights to refrain from cutting peat.

We advocate a full ban on peat extraction and peat importation. We should not be importing peat at the expense of any other country’s biodiversity.

Re-wetting, calibrated according to the ecological circumstances of each site, should be extended to all bogs in state ownership, at a minimum. Industrial infrastructure, such as wind turbines, should be located at appropriate locations offshore, not on bogs.

Scrub and Woodland

The amount of land under native woodland and scrub must increase to restore biodiversity and restore the natural vegetation pattern. This may be done directly by planting native trees sourced from seed obtained from indigenous sources as close to the planting site as possible, and by allowing land to re-wild of its own accord. The interventions needed in a natural re-wilding to produce the best results will be the removal of any non-native trees, such as Sycamore, which offer little by way of food for native invertebrates.

Woodland should not be planted on highly biodiverse grassland unless a managed grassland/scrub/woodland mosaic is to be created. Farmers should be incentivised to allow a proportion of their land to develop scrub, rather than being penalised.

Ancient woodland sites that have been planted with non-native trees or which contain invasive non-native plants should have their native tree cover restored; a project to remove exotic conifers and Rhododendron and restore Sessile Oak woodland is currently in progress albeit on a limited scale, in Glengarriff, County Cork[15].

Any new tree planting along roads, especially motorway embankments, should avoid the use of non-native species, which are completely needless in such locations. The choice of species should be the same as those found in the locality. This advice also applies to planting in public parks, public green spaces and verges.

Hedgerows

The law in relation to the closed season for hedge cutting and removal must be enforced throughout Ireland and should not rely on the selective and sporadic dedication of individual Conservation Officers.

Hedgerow management advice provided by Teagasc must take account of the needs to biodiversity and farming. Rotational cutting, allowing individual hedgerow trees to grow, and encouragement for hedgerow retention (grants and other incentives) should be advised by Teagasc.

No non-native species should be planted in hedgerows. Extended field margins adjoining hedges should not be ploughed, re-seeded, or sprayed with agricultural chemicals.

Pollution Threats

In addition to the comments made under the Grassland heading, more funding to increase grants to all homeowners to install solar panels is recommended to reduce pollution from the burning of fossil fuels. All public buildings should be fitted with solar panels. Power derived from wind energy must be increased with turbines located in areas where carbon sequestration, important habitats and species are not adversely affected.

The creation of more native woodland, re-wetting drained land will help to mitigate pollution.

Clear labelling should be introduced to inform consumers of the carbon and pollution cost of products such as mushrooms grown on peat substrates.

Farmers should be encouraged to deliver slurry and effluent to treatment plants instead of spreading the material on farmland. Treatment plants must be upgraded to deal with increased loads. Slurry should never be spread on semi-natural grassland.

Education

There is a great lack of biodiversity education in our primary and second-level schools. What coverage there is appears dependent on the enthusiasm of the individual teacher. In second-level schools, it is practically non-existent apart from the biology syllabus. Climate change is not the main driver of biodiversity collapse; habitat loss is the key problem.

Concern about climate change is often a celebrity-driven phenomenon, monopolising space better occupied by an awareness of the ravages caused by habitat destruction, especially of our wetlands, grasslands and woodlands. Remedying this damage will play a role in mitigating climate change impacts.

A broad appreciation for wildness, a love of nature, should be encouraged in our children. There is space in the second level curriculum, occupied by wellbeing, that can be dedicated to nature study. This can easily be integrated into the wellbeing programme: a day of tree-planting, a ramble in Glendalough, drain-blocking on a bog, pond-dipping, scrub control on a nature reserve, camping in a woodland, butterfly breeding and nature treasure hunts are all happy, healthy activities that can be carried out with or even without a detailed ecological context. Appreciation of such experiences can prompt curiosity, a desire to learn and to love nature.

The Transition Year programme particularly lends itself to environmental education. Modules should be developed by the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) for Transition Years to grasp the basics of ecology. This can feed into project work and may increase take-up of biology at senior cycle. The Environmental Studies module (optional for schools) (https://ncca.ie/media/2520/environmental_studies.pdf) could be developed further by developing the resources and connecting the material studied with complementary actions that effect or instigate real change, even if it is on a small-scale initially.

The worrying feature of the education of our professional ecologists is the dearth of knowledge frequently exhibited in ecological reports and in the field. The basics of habitat and species identification and knowledge of the ecological requirements even of species of conservation concern is disturbingly thin or entirely absent in some ecologists. There may be over-specialisation in the higher education training of ecologists; whatever the cause, it is disconcerting to see so few younger people with the knowledge required at this time of great need.

A Restructured National Parks and Wildlife Service

It should not take ten phone calls to reach the correct District Conservation Officer when attempting to report suspected damage to a Special Area of Conservation. The National Parks and Wildlife Service requires the correct complement of dedicated staff who are empowered to act to protect the environment without fear that their career progression will be negatively impacted by taking an ‘inconvenient’ case. Efficient, well-managed, well-supported competent staff are essential to any organisation. The courtroom should be the natural habitat for District Conservation Officers when environmental legislation is breached.

The capacity of the organisation to respond to planning applications that have the potential to negatively impact protected sites and species must be increased and maintained. The workload of conservation officers is frequently excessive with extensive geographical areas to cover. Some initiatives, such as the Burren Invertebrates Conference 2022, are excellent at showcasing the wonders of Ireland’s special places. To this end, the organisation’s website could be made much more attractive to view; while it contains important information, it lacks appeal for the general user. Furthermore, the premises used by the service are often hard to find, small and unattractive with little to inspire people. This should be remedied.

4 Conclusion

An integrated approach is required, involving in the first instance, farming, forestry, government, both local and national, planning bodies, especially An Bord Pleanála, professional ecologists and conservation and recording bodies, and conservation and recording volunteers. However, biodiversity loss is a challenge for society not just for those who can directly apply solutions on a more immediate level, because without a societal demand for change, the political will to effect change continues to be absent. We ask The Citizens’ Assembly to urge these recommendations on the Irish Government, to let those in power know that citizens want a healthy, butterfly-filled, nature-rich environment.

The Marsh Fritillary butterfly, Ireland’s only legally protected insect.

The Marsh Fritillary butterfly, Ireland’s only legally protected insect.

Jesmond Harding, Conservation Officer, Butterfly Conservation Ireland

About Butterfly Conservation Ireland

Butterfly Conservation Ireland (BCI) is a volunteer-run non-governmental conservation charity (Revenue Number 18161, Charities Regulator Number 20069131) founded in 2008 in response to the decline of our butterfly populations. BCI is dedicated to the conservation of butterfly habitats. BCI has a reserve at Lullybeg, County Kildare which we manage with Bord an Móna where conservation measures are applied to protect the excellent habitats so that the extraordinary butterfly and moth populations continue to thrive. We manage a reserve at Fahee North in the Burren in conjunction with the Burren Conservation Volunteers to protect Ireland’s rarest butterflies. BCI operates a recording scheme and shares the data with the National Biodiversity Data Centre. BCI holds events to showcase butterfly conservation and we provide regular educational content on our website and in our Annual Report. BCI provides advice concerning the conservation of butterfly habitats and advocates the protection and correct management of our landscapes.

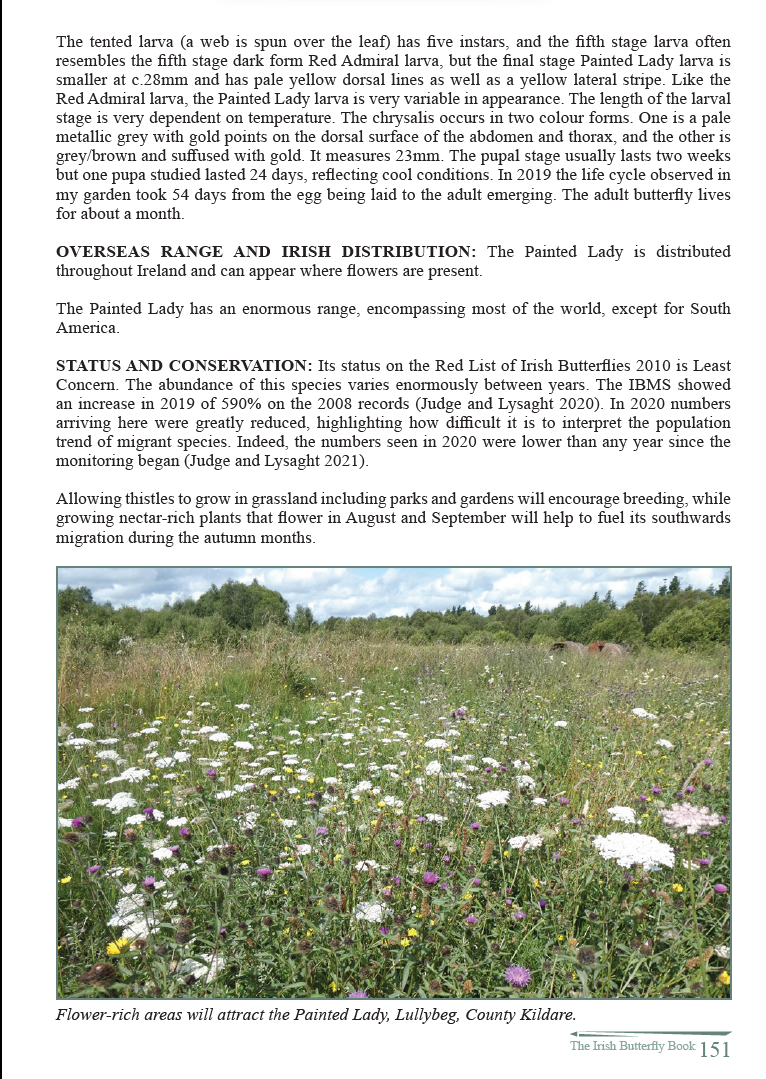

The Ballydermot Bog Group area, County Kildare, is the ideal location for a new national park for Ireland.

The Ballydermot Bog Group area, County Kildare, is the ideal location for a new national park for Ireland.

Footnotes

[1] https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2020/september/uk-has-led-the-world-in-destroying-the-natural-environment.html#:~:text=While%20countries%20such%20as%20Canada,UK%20only%20has%2050.3%25%20remaining

[2] https://butterfly-monitoring.net/sites/default/files/Publications/Technical%20report%20EU%20Grassland%20indicator%201990-2017%20June%202019%20v4%20(3).pdf

[3] Judge, M and Lysaght, L. (2022), The Irish Butterfly Monitoring Scheme Newsletter, Issue 14.

[4] Harding, J. (2021) The Irish Butterfly Book. Privately published, Maynooth.

[5] https://www.npws.ie/sites/default/files/publications/pdf/NPWS_2019_Vol1_Summary_Article17.pdf

[6] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D1PUk__cO_o&t=2180s

[7] Regan, E.C., Nelson, B., Aldwell, B., Bertrand, C., Bond, K., Harding, J., Nash, D., Nixon, D., & Wilson, C.J. (2010) Ireland Red List No. 4 – Butterflies. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Ireland, p.13

[8] https://www.npws.ie/sites/default/files/publications/pdf/Woodlands%20booklet.pdf

[9] NPWS (2019). The Status of EU Protected Habitats and Species in Ireland.

Volume 1: Summary Overview. Unpublished NPWS report, p.39

[10] Merckx, T., Marini, L., Feber, R.E., Macdonald, D.W., Kleijn, D. & Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet 2012, “Hedgerow trees and extended-width field margins enhance macro-moth diversity: implications for management”, The Journal of applied ecology, vol. 49, no. 6, pp. 1396-1404.

[11] Eeles, P. (2019) Life Cycles of British & Irish Butterflies. Pisces Publications, Berkshire, p138

[12] https://www.nationalpeatlandspark.com/

[13] Bonelli et al. (2021) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.108356

[14] Kurze, S., Heinken, T. & Fartmann, T. 2018, “Nitrogen enrichment in host plants increases the mortality of common Lepidoptera species”, Oecologia, vol. 188, no. 4, pp. 1227-1237.

[15] https://www.glengarriffnaturereserve.ie/

What path will our environment take? Semi-natural grassland, limestone pavement, scrub and woodland in the Burren, County Clare.

What path will our environment take? Semi-natural grassland, limestone pavement, scrub and woodland in the Burren, County Clare. The Marsh Fritillary butterfly, Ireland’s only legally protected insect.

The Marsh Fritillary butterfly, Ireland’s only legally protected insect. The Ballydermot Bog Group area, County Kildare, is the ideal location for a new national park for Ireland.

The Ballydermot Bog Group area, County Kildare, is the ideal location for a new national park for Ireland.