One of life’s annoyances is arriving back in Ireland after a break in a sunny clime to be told by a grinning neighbour, “The weather was amazing here when you were away. It only started to rain yesterday.”

Anticipating this scenario while in Malta, I checked the weather report and forecast for Ireland online on RTE Radio. Rain, wind, thunderstorms, flooding, etc, etc! No mention of sunshine! Just lots of the wet and windy stuff.

That morning I gazed through the window of the apartment in Għajnsielem, Għawdex (Gozo, nicknamed Il-Gżira tat-tliet għoljiet, the island of the three hills), at clear skies lit by the Mediterranean sun. The smug feeling that comes from knowing that I wouldn’t be on the receiving end of a meteorological putdown and that I was feeling that glorious Vitamin D delivering sunshine on my pale skin was delicious.

Gozo, also known by its residents as Għawdex is the second largest of the Maltese Islands, which are the sunniest in Europe with over 3000 hours of sunshine a year. The sun shines for about 300 days each year. The winter temperatures are benign, with highs of 16-18 Celsius on many days. The average annual temperature is about 23 Celsius. In Ireland, the average is 9.4 Celsius. This is considerably lower than the average of 12.4 Celsius in Malta’s coolest month, February.

Temperatures in April this year (2023) reached around 23 Celsius, a comfortable heat. It rained once during my two-week stay. It gets hot later, with June to September regularly having temperatures in the 30s Celsius and sometimes higher. The highest temperature in 2022 was in August when 39.2 Celsius was recorded. Being surrounded by sea means the very extreme high temperatures seen on the European mainland are avoided. Rainfall is low compared with Ireland and occurs mostly during winter. Summer rain is very rare. The islands get about 600mm of precipitation per year, sometimes much less.

The inhabitants accommodate themselves to the high day-time summer temperatures by closing businesses from 11 am to 4 pm (typically). Heat can be troubling for those with an aversion to high temperatures so if that’s you, avoid visiting from June to September because you will not enjoy your stay. During these months, there is persistent heat, even at night.

The islands are special for their history, culture, and extraordinary architecture. The main island’s buildings were largely reconstructed after World War II when the island was essentially flattened by Axis bombing; Field Marshal Kesselring told the German High Command that “There is nothing left to bomb.”(Holland, 2003). The formerly iconic opera house in the capital Valetta (named after the French nobleman Jean de la Valette, who is recalled in the city’s name for his incredible feat in defeating the Ottoman invasion of Malta in 1565, one of the greatest sieges ever fought in Europe) remains a bombed ruin, a memorial to the devastation wrought on the island, a major strategic target in the Mediterranean war theatre.

For me, the islands are of immense interest, some of them rooted in the personal, given my Maltese heritage. The islands’ biodiversity is a big draw. As with isolated islands, the biodiversity count is lower than it is on continental land masses, but some of the species have developed unique characteristics, probably by being geographically isolated for thousands of years.

There are, for example, several endemic species and subspecies (an endemic is a species or subspecies that is confined to a restricted area) as well as near-endemics present, adding interest. Its strategic importance during conflicts also applies to biodiversity; it remains strategically important as a migration stop-over for many birds and insects.

The most eye-catching butterfly is Papilio machaon melitensis, the unique endemic subspecies of the swallowtail butterfly that occurs only on the Maltese Islands. Large, elegant and powerful in flight, it is undeniably beautiful. The subspecies rank of this butterfly was established in a study carried out by the University of Munich in 1936. Karl Eller researched the species based on specimens caught in September (probably the third generation).

Eller concluded that the Maltese swallowtail has a very long forewing, that the broad dark band running along the submarginal area of the forewing is strongly wedge-shaped and that this band, continued on the hindwing, is very broad there where it almost merges with the red spot. He also noted the finely scaled veins on the hindwing upper surface and found the red flame markings on the hindwing underside to be prominent. Eller considered the swallowtails he found in Malta similar in appearance to those in Africa.

Recently, Leraunt (2016) stated his belief that the swallowtail in Malta is in fact a different species of swallowtail, mainly found in North Africa and the Middle East: “Illustrations on the Internet of melitensis Eller from Malta convinced me that it is indeed P. saharae melitensis Eller, 1936, stat. rev.” This view that the Saharan Swallowtail occurs in Malta was challenged by Louis Cassar (2018) of the Institute of Earth Systems at the University of Malta:

Leraut does not provide convincing evidence based, for example, on morphometric analysis (the study of shape variation of organs and organisms and its covariation with other variables) or molecular characterization to substantiate his hypothesis.

Given Louis Cassar’s morphometric study of both species (all life stages), I concur with his view. Differences exist, for example, in the antennae, the size and shape of the red hindwing spot, overall size, the appearance and length of the pupal stage, egg size and larval colour and the length and colour of the osmeterium (this is an eversible forked organ concealed just behind the larva’s head that emits an unpleasant smell used to repel bird attacks). This does not mean that the Saharan Swallowtail never appears in Malta; given the nomadic habits of many swallowtails, it may occasionally migrate there from North Africa and from Lampedusa, an island about 150 km WSW of Malta where the Saharan Swallowtail was recently confirmed (Cassar et al. 2023).

Butterflies don’t care about their own taxonomic identity, but we must. Species confined to a small island group deserve study and may require protection and our appreciation as we marvel at the ability of nature to adapt to conditions that may differ significantly from those on a continent.

Certainly delightful, the swallowtail in the Maltese Islands appears to be successful, moving throughout the landscape and even island-hopping to seek mates and breeding sites. Netted with black veins and bands over yellow wings, the sharp blue hindwing band and flame-red spot and black tails spell sophistication. So does its behaviour. It flutters delicately above blooms while dipping its proboscis to suck nectar, then surges powerfully away, defying gravity and gale in its onward propulsion.

One of the loveliest sights is a primrose yellow swallowtail fluttering around red or purple Bougainvillea climbing on mellow yellow ochre Maltese walls.

This butterfly is oddly elusive. You can look for it for hours, be on the brink of admitting defeat and then see three at once, battling for possession of ground or pursuing a mate. The courtship is dramatic. The sexes flutter around each other before rocketing to an impressive height and then plummeting to pair on a low shrub. Territories are often held on a patch of ground containing larval foodplants and nectar sources.

Some of these are at altitude and may also function as hill-topping sites where territorial possession and mate-seeking may occur at the same time or transition to hill-topping behaviour. This is when some butterflies, especially males, fly for hours around an exposed elevated site, with little or even no clear or discernible purpose. Mates may be encountered at hill tops but in some species, this appears not to be the purpose; for example, Peacock butterflies that are in a breeding delay phase (diapause) have been seen hill-topping in the Burren.

The swallowtail in Malta breeds mainly on Fennel Foeniculum vulgare which occurs widely and is often abundant. Fennel is also a nectar source. Fringed Rue Ruta chalepensis is also used for breeding. According to online sources, the adult butterfly flies from late February until November. It passes the winter in the pupa.

When I visited in the last two weeks of April, the adults I saw were mainly very fresh specimens. I also found young caterpillars on Fennel. It is possible that I was seeing some second-generation butterflies by late April, but I am not sure. The larvae were, I presume, the offspring of the first generation and will be second-brood butterflies.

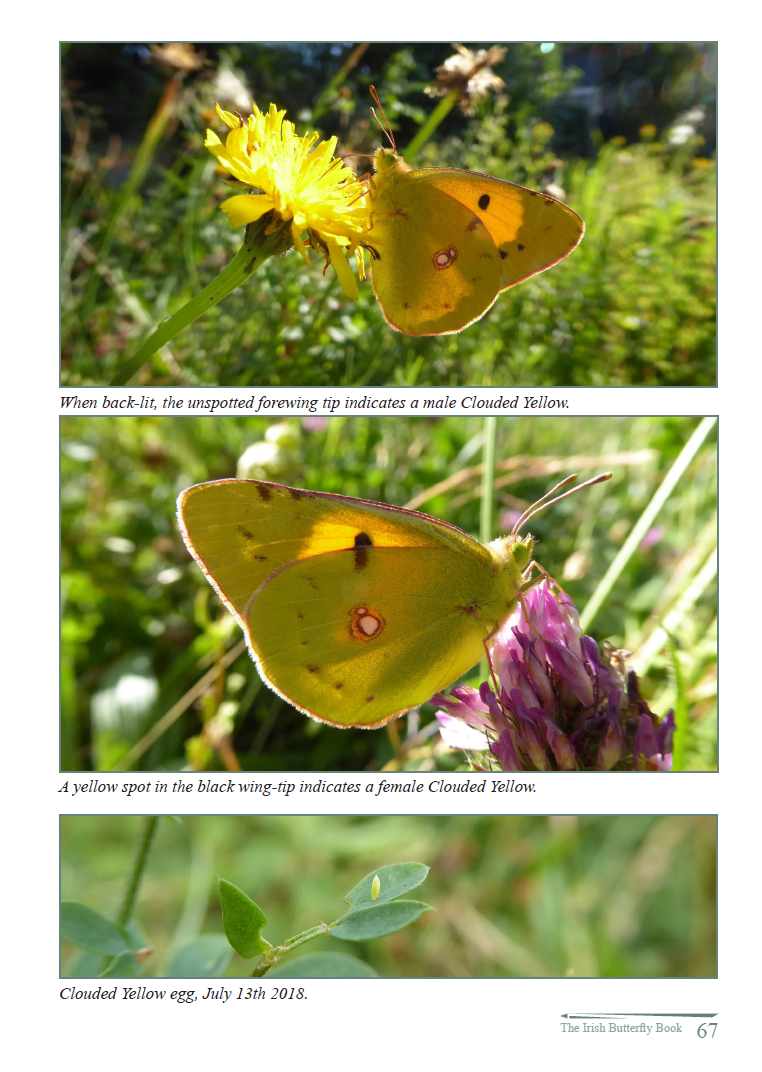

There were many butterflies flying in April. Small White, Large White, Eastern Bath White and Clouded Yellow were busy feeding and breeding. I saw Small White laying eggs on Caper Capparis orientalis, a lovely low shrub with striking flowers, especially the violet stamens. The flower buds are edible for humans.

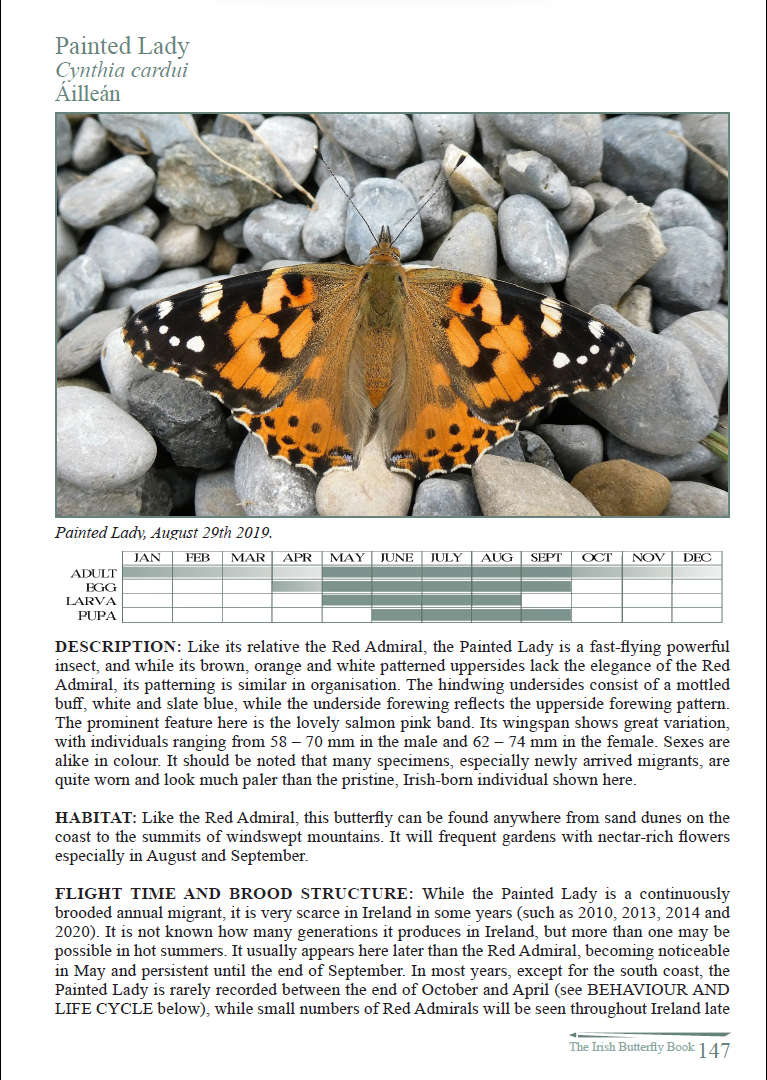

Three blues were busy: Lang’s Short-tailed Blue, the Long-tailed Blue and the Southern Blue, previously believed to be the Common Blue. The classic migrants, Red Admiral and Painted Lady, were out too; some of the latter were faded and tattered, and others were perfect specimens.

The Wall Brown butterfly was abundant and I even saw a female on the main street in the Gozo capital, Victoria (Rabat). In Malta, none of these species needs very special habitats; they just need larval foodplants and nectar sources. I saw one Meadow Brown, on 29th April, near the coast east of Qala village. He was freshly emerged and I was excited to see it. However, the sight of what was recently a common butterfly should not typically evoke animation, but its populations on the islands are parlous:

A somewhat rare resident species that has experienced a sharp population decline in the last decade or so. The species still maintains small, fragmented populations in a couple of localities, but current trends do not bode well. (Cassar 2018)

The Meadow Brown exists in Malta as an endemic subspecies, Maniola jurtina hyperhispulla. Its extinction would therefore be especially tragic. The decline of this and other butterflies (Small Copper, Small Heath, Speckled Wood) might be linked with pollution, climate change and habitat loss, all in evidence on the islands. Chemicals are heavily used in farming to extirpate insects. Even in unfarmed land, bird trappers use persistent herbicides to remove vegetation from trapping sites. In recent years, precipitation levels have declined significantly below the average. The unrelenting building frenzy is swallowing precious land especially in Malta but also in Gozo.

Three ‘new’ butterflies have arrived on the islands in recent years. These are the Geranium Bronze Cacyreus marshalli, Dark Grass Blue Zizeeria karsandra and Desert Babul Blue Azanus ubaldus. The first occurs naturally in South Africa and may have arrived on imported Pelargoniums while the latter two are species of hot, arid lands, essentially eremic (desert) species. The survival of these three in Malta points, possibly, to the warming, drier climate there, and must be concerning for the habitats and native species currently supported.

All is not gloom. Maltese people are beginning to take their environment’s needs into account. A nature park covering 2.5 sq. km, Il-Majistral, was established in 2007 in the north of Malta. Malta has also declared protected areas covering about 29% of the land area and 35% of marine waters. No more bird-trapping licences are being issued, and shooting is less accepted now, but these activities continue. Some birds, like the Honey Buzzard and Marsh Harrier, are easy targets owing to their lazy, soaring flight. Further work will hopefully make shooting such species a thing of the past.

There is still much to see in the Maltese countryside, especially for a person from cooler climes unused to seeing the plant and insect life in the Mediterranean.

The friendliness and openness of Maltese people is a tonic too. A welcome is rarely if ever withheld. There is a distinctive culture. Signs of the religious culture are evident everywhere with churches in every village. Crucifixes hang in public places from government buildings to insurance offices. There is less restraint in speech, with a directness rarely heard elsewhere. The village is a key part of identity, and for many people the next village, a kilometre or two away, is considered a great distance to travel.

The squares are the centre of village life, and news travels fast. During the heat of summer, most social life occurs after dark, and the village squares come to life. Children chase one another around tables and street furniture and climb into niches in the baroque churches. Safe, friendly and memorable, you will certainly experience something different.

If there was only one thing I could change, it is the rampant construction of apartment blocks, which I would like to see ended. After that, I would ban pesticides. But that applies to Ireland too, along with massive fertiliser inputs.

Without a better way of managing food production, the glories of our world will continue to diminish. Wherever you visit this summer, try to visit sites with high nature value. The message that nature matters might hit home the better.

Photos J. Harding

References

Cassar, L. F. (2018). A Revision of the Butterfly Fauna (Lepidoptera Rhopalocera) of the Maltese Islands Summary. Naturalista Sicily, S. IV, XLII (1), 3–19.

Climates To Travel World Climate Guide (2023). Available at: https://www.climatestotravel.com/climate/malta (Accessed 06 May 2023)

Holland, James (2003). Fortress Malta: An Island Under Siege, 1940–1943. London: Miramax Books.

Ireland’s Blue Book (2023). Available at: https://www.irelands-blue-book.ie/IrishWeather.html#:~:text=Temperature%3A,C%20(60.3%20%C2%B0F (Accessed 05 May 2023)

Papilio machaon subsp. melitensis Eller, 1936 in GBIF Secretariat (2022). GBIF Backbone Taxonomy. Checklist dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/39omei accessed via GBIF.org on 2023-05-06.

Weber, Hans and Kendzior, Bernd (2006). Flora of the Maltese Islands A Field Guide. Marburg: Margraf Publishers.